We interviewed Andrea Burgay to speak about her latest project, the Breakdown exhibition at Distance Gallery. Art in times of crisis, the place of art in the “new normal” and how we need to breakdown before making something new are some of the topics we discussed with her. Also, we asked her to interview China Marks, one of the artists that she lined up for the exhibition, whose work with fabric are some of our favorites pieces from the show.

TWS –Can you tell us about your latest curatorial project, the Breakdown exhibition?

AB –Breakdown is a virtual exhibition of artwork made through processes of fragmentation and rebuilding. The show is on view at Distance Gallery, an online exhibition space founded by artist and professor Joshua Field. He launched Distance Gallery after the coronavirus pandemic shut down all physical museums and gallery spaces here in the US. I was thrilled when Joshua invited me to curate a collage exhibition. The ideas that formulated this show had been on my mind for some time.

The term “breakdown” has a very negative connotation—someone or something is falling apart completely. It’s something we don’t generally want—we want to maintain productivity and progress. But a breakdown also offers a potential previously unavailable, a potential to examine the parts of something and put them back together in a new framework.

In the exhibition, Breakdown refers to the desire to deconstruct something to understand it more clearly. The artists in Breakdown physically destroy, deconstruct and disassemble. They break down books, images, raw materials and their own artwork. Resurrecting the fragments that remain, they create new narratives. Reassembled, the broken pieces reveal new meaning and visions, showing us new paths and ways to rebuild.

Courtesy of the artist.

TWS –All the artists selected for the show deal with fragmentation and reconstruction on different levels. What did you have in mind when choosing the artists?

AB –Breaking down images to make them into something new is inherent to collage work, often embodied in the overused phrase “cut-and-paste.” I wanted to explore how these methods of deconstruction and rebuilding expand throughout many types of media. I wanted to investigate how these methods differ and converge and what they express.

The artists in the exhibition take apart and reconfigure a wide range of materials resulting in works that range from two-dimensional collage to sculpture and installation. I’ve long admired the work of Todd Bartel, Adam Brierley, Judy Hoffman, John Hundt, China Marks, Max-o-matic and Helen O’Leary, and I was very excited to bring their work together under the umbrella of Breakdown.

Though taking vastly different forms, many of the artists in the exhibition use techniques to deconstruct familiar imagery and disrupt or readdress its meaning within new contexts.

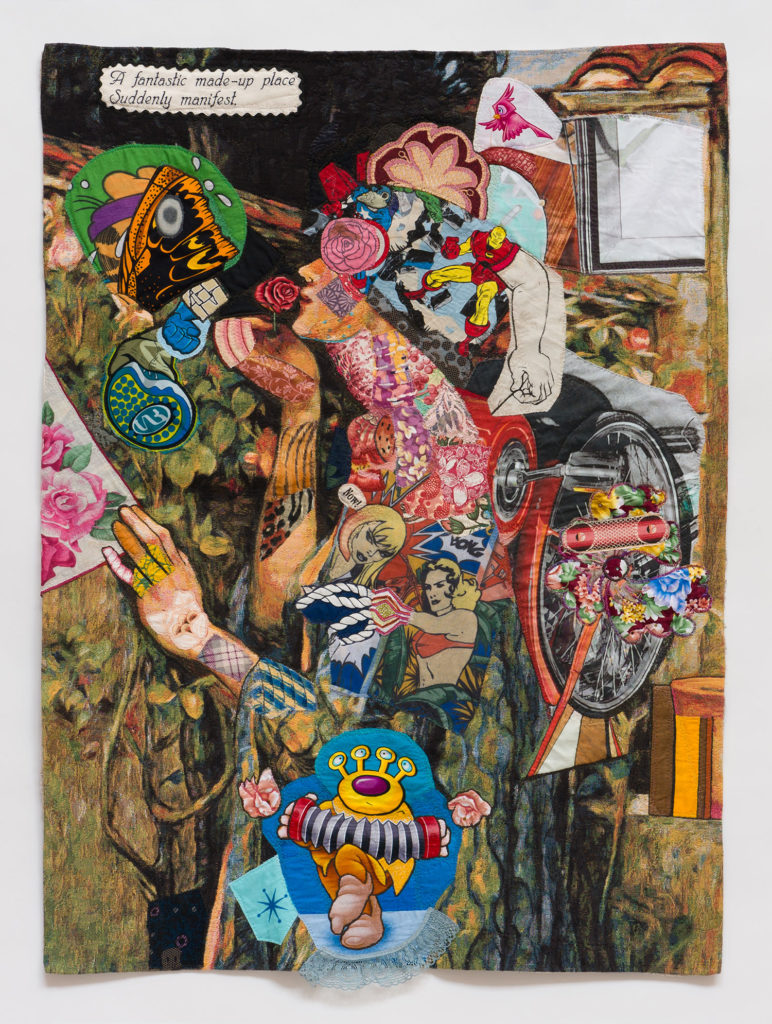

China Marks uses fabric scraps to create characters and worlds that subvert the familiar and reflect the absurdity of our own world back at us. John Hundt uses paper elements to build landscapes that subtly embody social issues and historical events.

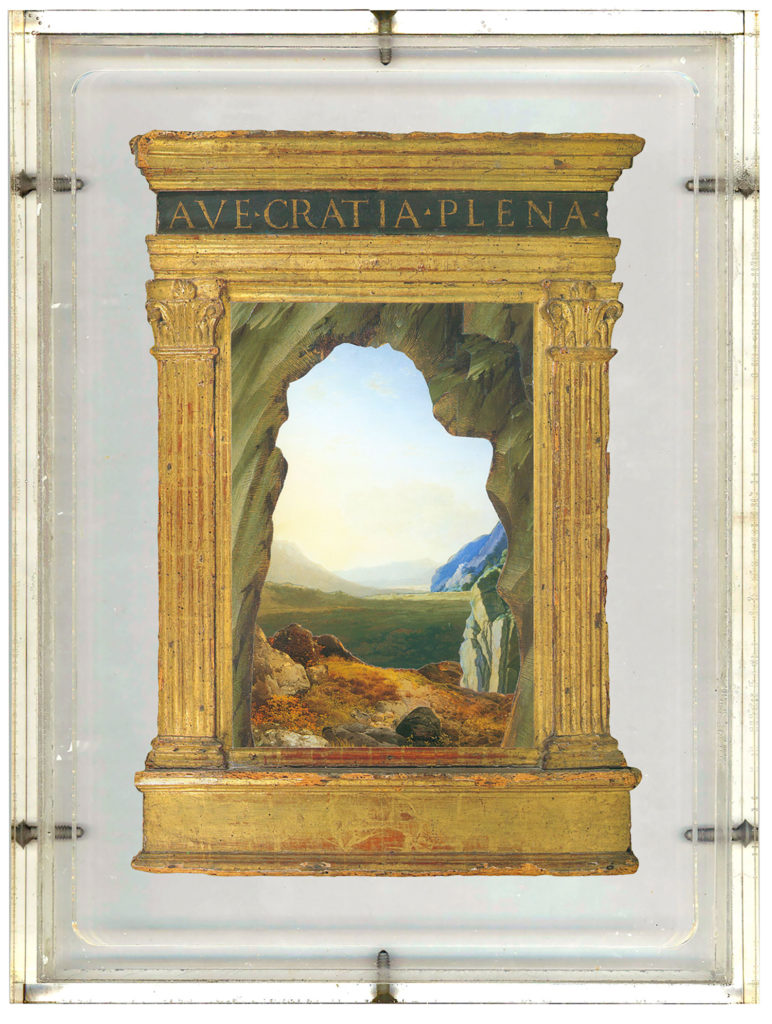

Todd Bartel deconstructs the history of landscape painting, creating “landviews” that encourage us to reimagine our relationship with land and how we interact with it. And Max, your works, from the Velazquez Hacked series, juxtapose and interject contemporary images and historical paintings.

In other works, the concept of breakdown references the transitory nature of existence, loss and reconstruction of stories and memoir and the organization of chaos.

Judy Hoffmann’s ceramic works are made through building, then breaking down her own work, referring to cycles of creation and destruction. Helen O’Leary’s sculptural paintings are an archeology of delicate fragments constituting memoirs of her life growing up in Ireland and relocating to the United States. And Adam Brierley’s energetic large-scale works on paper combine vintage imagery with hand-made marks simultaneously referencing destruction and nostalgia.

TWS –The title of the show is Breakdown. How much is this a political title and how does it fit in the context of the pandemic and the social crisis that America is going through right now?

AB –The idea for the show was conceived before COVID-19 hit and before the murder of George Floyd ignited this new phase in the fight for racial justice. So, these events weren’t what I was channeling with Breakdown, but it’s hard not to see connections.

Initially, I was curious to understand the artistic implications of the “breakdown” process, the desire to disassemble and deconstruct. I wondered about the underlying psychology of the artists who work this way, including me. Are we trying to rebuild ourselves as whole beings after trauma? Are we trying to understand our experiences, or the world around us?

But just as individuals need to rebuild after trauma, societies and groups of people need to follow a similar path. The United States has reached a breakdown. And once any structure breaks down, the inner workings are laid bare. The COVID crisis here has exposed many things—the lack of foresight and care for people by our government, the fragility of our democracy and the systemic racism that has been part of the country since its inception.

But this state of “breakdown” is, again, where potential lies. We have to acknowledge all of the things that are now made clear, all of the ways that systems are unjust and nonfunctional. We have to dismantle and pull apart what is harmful and build anew.

TWS –What is the place of art in the context of such relevant social events?

AB –That’s a big question. I think that artists should speak to and support truth and justice in whatever way they can. As the creators of our cultural voice and imagination, it is artists’ role to reveal that which may be hard to visualize and show new possibilities and ways of thinking.

I am thinking about the illustrations of the victims of police violence that honored these people and connected us to their lives. I am also thinking about all the artists whose work directly address racial injustice—autobiographic, documentary or exploring systems of oppression in different forms. Many artists have used their skill to design visuals that communicate information, used their work to fundraise and devoted themselves completely to protests during this time. I think the role of the artist is the same as the role of the human—use what you have and do what you can to make a difference.

TWS –Breakdown is an online exhibition hosted on Distance Gallery. How do you envision art in this upcoming “new normal”?

AB –I think that virtual exhibitions will be the new landscape for viewing, at least for the time being. It’s been a thrill to work with the Distance Gallery. But I would also love to have a physical exhibition of this work. Detail, texture and scale don’t fully translate to screens. The essence of the work persists, but the visceral experience is lessened.

Digital shows can reach much larger audiences and are easier to organize. The reliance on this format until there’s a COVID vaccine may signal a shift towards more work that is suited to a digital platform—perhaps work that is technologically based.

But I think, as is really already the case, that this will make us yearn for the tactile, an experience with something we can be present with and relate to in real space. I miss the experience of looking at art that entirely encompasses my attention, without the pull of texts and emails in the background. I miss the physical world.

The exhibition:

Breakdown is on view at Distance Gallery from June 15 – July 15

An accompanying exhibition catalog will soon be available. Contact Andrea to get more information about it.

Breakdown artist feature:

Andrea Burgay interviews

artist China Marks

AB –What are you “breaking down” in these complex fiber-based drawings?

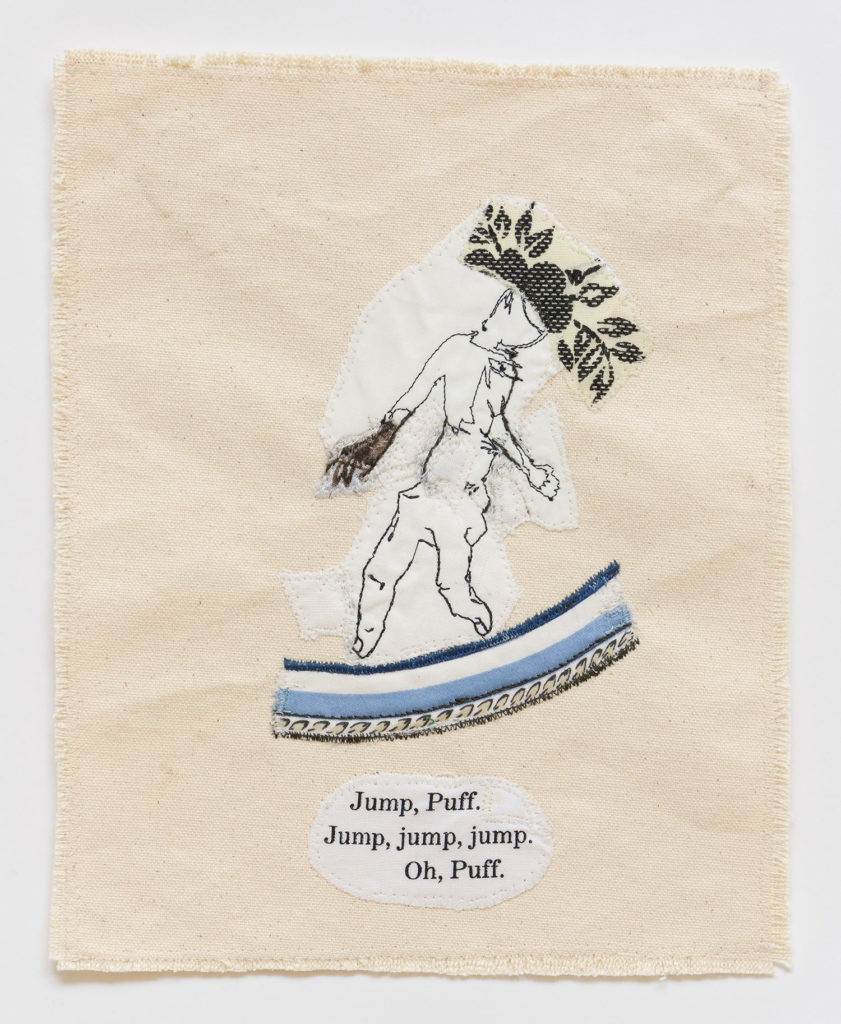

CM –My drawings are derived from bits and chunks of imagery from a wide range of patterned fabrics, found printed clothing, needlepoint, various kinds of trim, etc., as well as scraps left over from previous drawings and old silkscreens of mine from the early 90’s, printed on fabric. I have many boxes of scraps, as well as fabric bought on trips or given to me. I also have both sewn and printed text, some of it left over from previous projects.

So, in effect, I construct my drawings from what has already been broken down and made profoundly incoherent.

AB –In the premise for the Breakdown exhibition, I state that artists break things down in order to transform and rebuild. What does this process of transformation express in your work?

CM –Well, yes of course, my drawings are transformative, I mean, why make something that already exists?

First of all, my drawings are narratives. I use a great variety of found imagery to create narratives that reflect our present circumstances and how we negotiate issues of power and transcendence. At the same time, my drawings are artifacts of process, objects as well as images.

Meanwhile, the essential nature of my time-based artmaking requires me to relinquish control and to remain open to chance. This generates a wide range of imagery and formal solutions that I would otherwise not have access to.

I make these drawings because it is the most interesting thing I have ever done and I can hardly wait to see what happens next.

There’s something about this medium, by which I mean using an industrial sewing machine to draw with thread into fabric, and since 2013, also using a computerized embroidery machine and CAD software—that suits me very well, perhaps because it is such a makeshift, hybrid art form, employing materials and machines meant for the manufacture and ornamentation of clothing, along with hand tools like pliers and screw drivers, not customarily used for drawing.

This medium has such richness that it will take the rest of my life to unpack its possibilities. Though it is very hard work, with thousands of knots to be tied and interminable doing, undoing, and re-doing until I get it right,

I have given myself over it, becoming in effect as much an instrument of the process as any of my machines.

Courtesy of Owen James Gallery.

AB– Many of your recent works are made on contemporary tapestry copies of historical art works. How do you interact with the history of these objects, now removed and translated multiple times from their original form?

CM –Since the fall of 2014, in addition to one of a kind books and miscellaneous other drawings, I have been working on a series of drawings on contemporary tapestry copies of 14th-21th century paintings, variously collaging and sewing into them, subverting both imagery and narrative, and writing dialogue and commentary which I embroider out and sew down. I call the finished drawings “altered paintings,” which does not make clear how much was already done to them before I ever laid a hand on them: how badly copied, cropped, edited they were, how coarsely re-decorated, and finally woven pixelated on digital looms using modern yarns. In effect, just like the rest of our history, they had been massively and repeatedly interfered with. In fact, that is why I like working with them.

AB –In your work, disparate components merge to form disjointed characters that move, speak and interact. Where do these characters come from? How do they evolve?

CM –As noted above, I am not in charge. But I believe that my drawings tell stories that reflect the world we live in.

Courtesy of Owen James Gallery.

AB –These characters inhabit alternate universes created from metamorphosed scraps and bits of our present world. How do these alternate universes connect to where we are?

CM –What you consider an alternate universe is our own world, seen at a slant, a cruel but fascinating place.

In effect I use broken-down bits of imagery to construct strange but compelling narratives instead of the usual stories of who we are and what we do and why it matters, which is always the same thing—buy something, watch something, eat something, find God, and so forth.

Courtesy of Owen James Gallery.

Find more about Andrea Burgay and China Marks.