TWS –Hi Michael, can you please tell us anything you’d like us to know about yourself?

I grew up in a suburb of Chicago the son of a Colombian immigrant. While my father was physically out of space, growing up bi-racial in a mostly white suburb which left me feeling emotionally out of place. I often got teased for having a weird last name and a Dad with a ‘funny’ accent. I turned to drawing and disassociating as a coping mechanism and began getting lost creating my own little worlds in the margins of my notebooks, reading comic books and digging into science fiction and fantasy novels. It was difficult growing up being so distant from one side of my family identity, all of our immediate family on my Father’s side remained in Colombia where it was unsafe to travel in the 80’s and 90’s thanks to America’s war on drugs, something I wouldn’t come to understand until I was in college. I gravitated toward HP Lovecraft as a teenager and began making drawings based on his short stories and novels and submitted that body of work which got me accepted to Art School for college. I was fascinated with the way Lovecraft played with storytelling blending the familiar and the everyday with the extraordinary unknown as well as weaving in his ideas of the ‘fear of the unknown’ or ‘fear of the other’. I trained as a printmaker in College and I worked for 6 years thereafter for Chicago based Artist Tony Fitzpatrick as an assistant and studio manager before relocating to New Orleans in 2009.

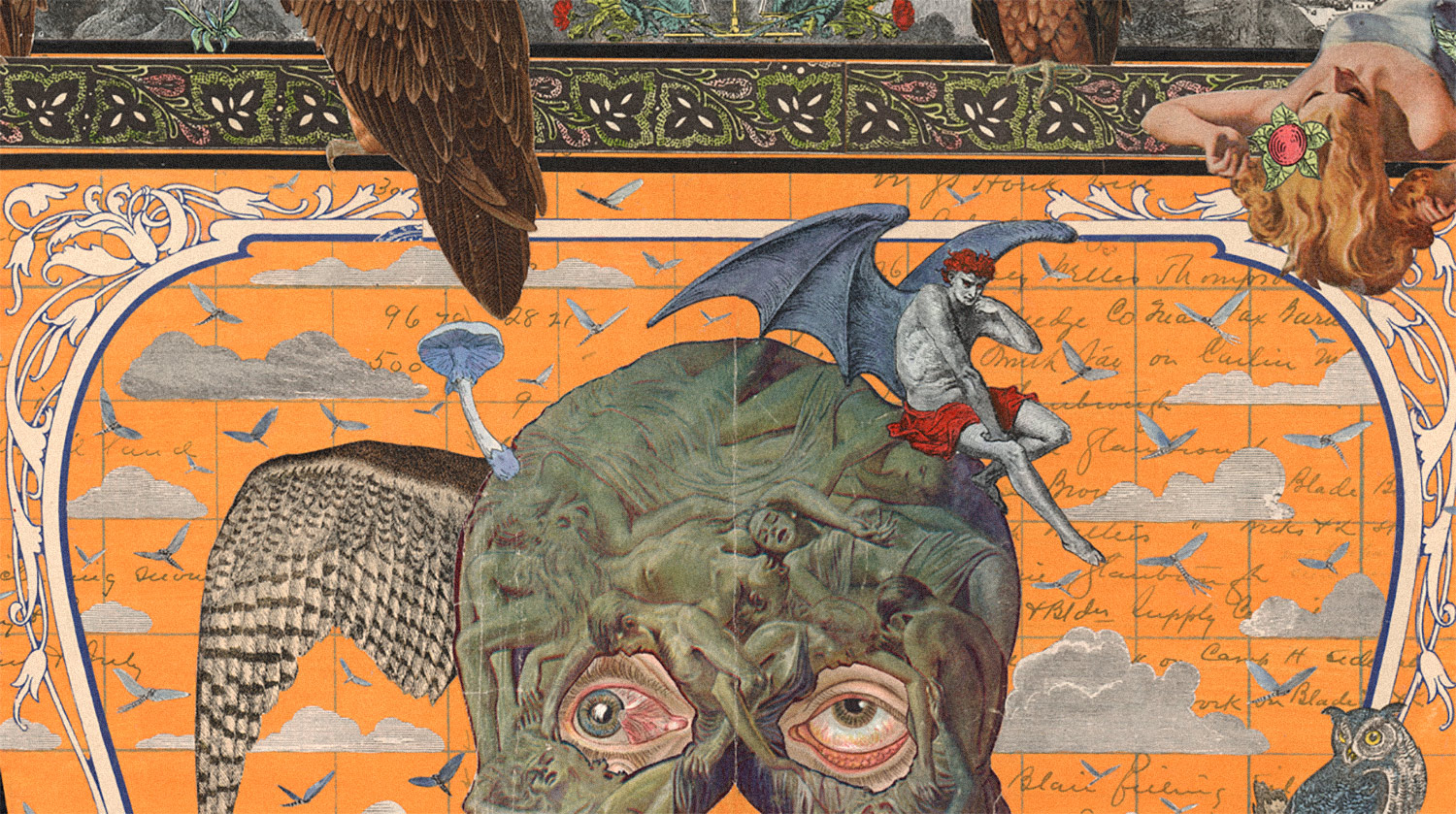

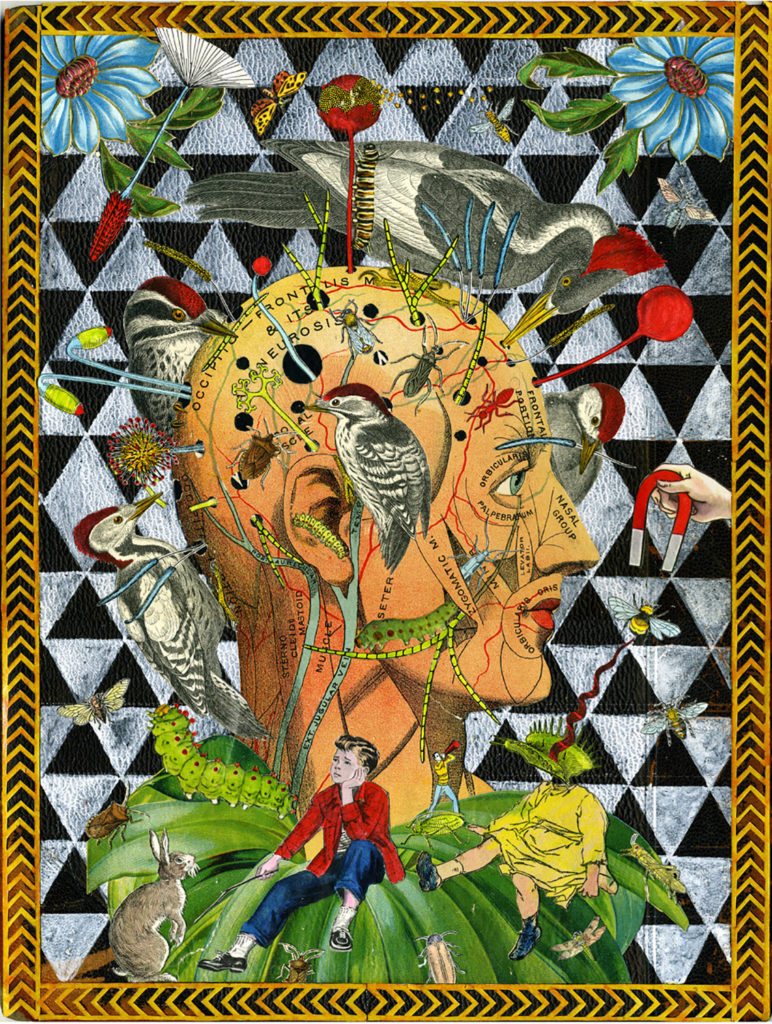

Mixed Media Collage on Book Covers

15 x 5in. 2014

TWS –You mention that you want to “evoke a sense of place” with you art. Which is this place? How does it look? Can you tell us something about this imaginary travel that you want to take us with your work?

I had a hard time connecting with the place I grew up and the small town attitudes there. My Father had no deep ties to it really, and my mother had grown up in the City of Chicago but preferred the space of the suburbs. I grew up in the kind of suburban sameness that was critiqued so well in movies I love like Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands. Simultaneously I have all of these stories that my Father is telling me about growing up in Bogota, the mountains, the jungle everything sounds unbelievable and exotic to a kid growing up in the Midwest.

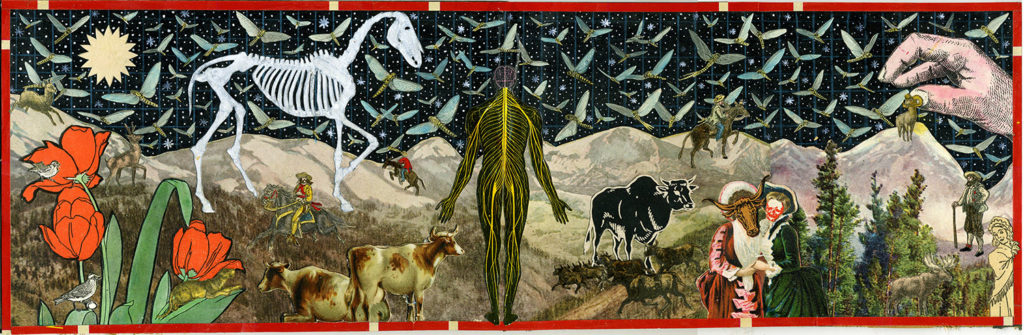

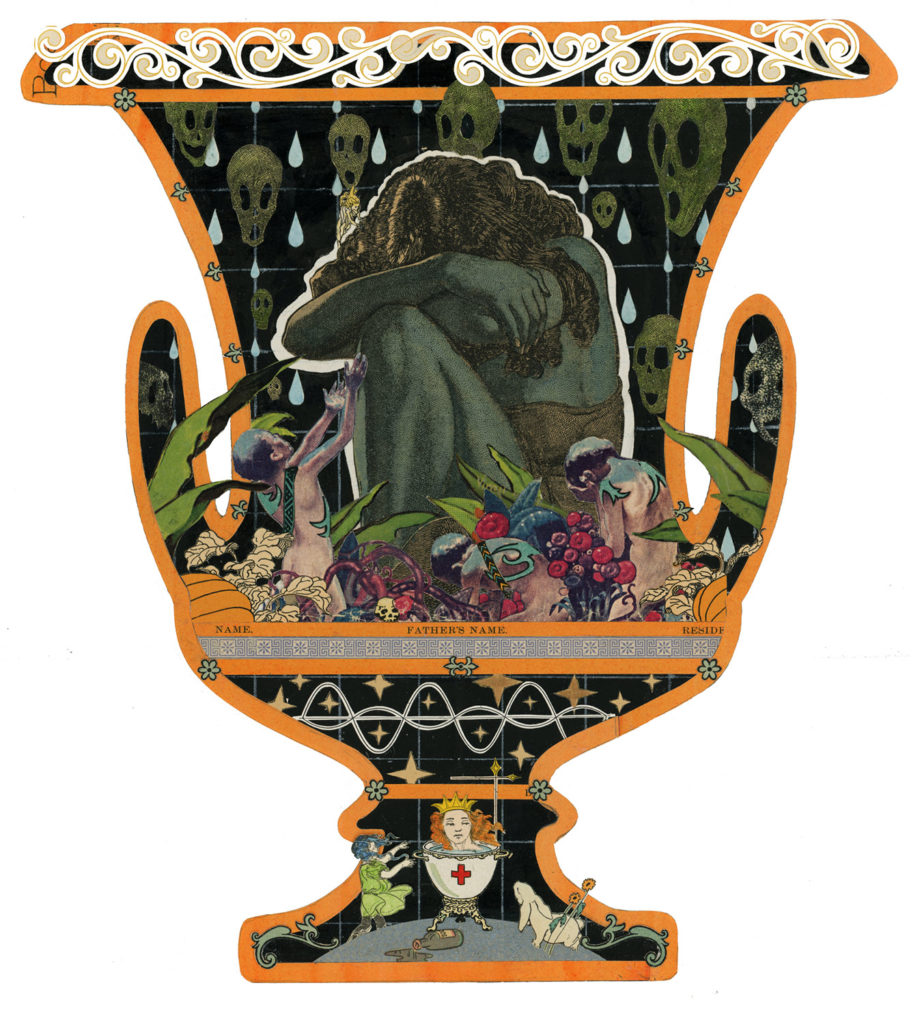

So I find myself creating these kind of spaces that have a familiarity but also a of rich sense of itself. A uniqueness that looks for beauty in the decay and wonder at the manufactured and imagined landscapes around us. I inhabit these spaces with the kind of misfits, weirdos and underdogs I root for in the kind of media I love. Costuming and masking culture in New Orleans during carnival season allows for all kinds of wonderous shapeshifting to occur and for people to express themselves in the most delicious ways. The parades and costumes transform the city for more than a month every year, it’s a very special and magical time that absolutely influences my work. So the place I am trying to create speak to that because I always want it to be growing, shifting and transforming.

The ‘sense of place’ I seek in my work also comes through the very language of collage to act as web of memories or impressions layered over one another. When my Father passed suddenly in 2003, the ‘sense of place’ we used to occupy together suddenly only existed in my memory. That memory is a fickle place and it can be hard to recall certain moments with any detail, while others might hold great clarity like significant events, birthdays, family vacations. These are often points of great connection that create long lasting bonds which makes some of those memories clearer and easier to access.

Mixed Media Collage on Antique Book Covers

27 x 10-1/2. 2016

TWS – You work blends the encyclopaedic with the surreal. Can you please tell us something about your approach to storytelling?

Yes, I think I enjoy dissecting the encyclopedic so much because the desire to categorize, document and catalog the world is such a strange human compulsion. The need to label understand, define and create maps and boundaries of people places and things is a coping mechanism for the great chaos that is life and our environment. Bringing it back to Lovecraft for a moment, his idea of the ‘unknown’ is the border of where reason and superstition lie, where our imagination fills in what facts cannot. I feel like my storytelling technique is impressionistic and intentionally esoteric at times and exists on that line.

TWS – Your work seems that tries to re-write (or at least re-think) history, mixing layers of past knowledge into new narratives. Why you choose to use the past as direct source to create your art? and what does attract you from the images of the particular era you use… why you choose this period and not others?

I’ll speak to the material choices first, as a printmaker I am absolutely smitten with printed matter. I prefer the saturated colors of chromolithography, the impressions engraved images, and the whimsy of children’s book illustrations. It’s fascinating to sometimes see the same image used again and again in various publications some times decades apart.

In many of my earlier works I was digging into fables and fairy tales for inspiration. While researching them I came across articles describing how many collections of folklore and folktales became white washed in the process of translating them from the oral tradition of story telling to the written page. The perspective of the author being superimposed throughout every translated tale. Perspective matters, and when I think of history I see the same pattern repeated, old white men controlling the narrative of what gets published and what and whose history is deemed important.

The idea of rethinking history is that it’s far more fluid than we think. Growing up in the United States so much of the history we are taught is minimized, glossed over and presented to us as children without context. So simply by omission of information there is a failure to present history in an accurate way. Many of the tomes I have collected are riddled with racist and out dated modes of thinking that were presented as fact in their day. When I look at the publishers names and do any minimal research it’s easy to see that the entirety of history is also a matter of perspective, especially when it comes to who chooses how the facts are represented. If wealthy white men create a written history for the public to consume, those will become the facts because they want history to favor their legacy. Living in New Orleans for 11 year I have watched as activists have called for, and successfully removed racist monuments put up throughout the city decades after the Civil War, installed by descendants of Confederate soldiers as symbols of oppression designed so the formerly enslaved never forgot who was in charge. It’s important to question the dominant history and monuments and markers that support it that often confuse myth and fact. Who presented this history? What are their motives? Are their other persepctives/ideas that existed at that time that challenged the dominant and normalized history we grew up learning? There are so many groups of marginalized people who are only now getting their voices heard and that’s who I am paying attention to and whose wisdom I seek out.

Mixed Media Collage on Panel

26 x 25in. 2019

Mixed Media Collage on Antique Book Cover

19-1/2 x 16-1/2. 2017

TWS – In your statement you mention that you want to want to offer the viewer a roadmap of America, imagined and real. And in your collages there are traces of different cultures (oriental vases; european encyclopedism; comics, etc). Can you expand on your idea of this imagined America that you’re creating?

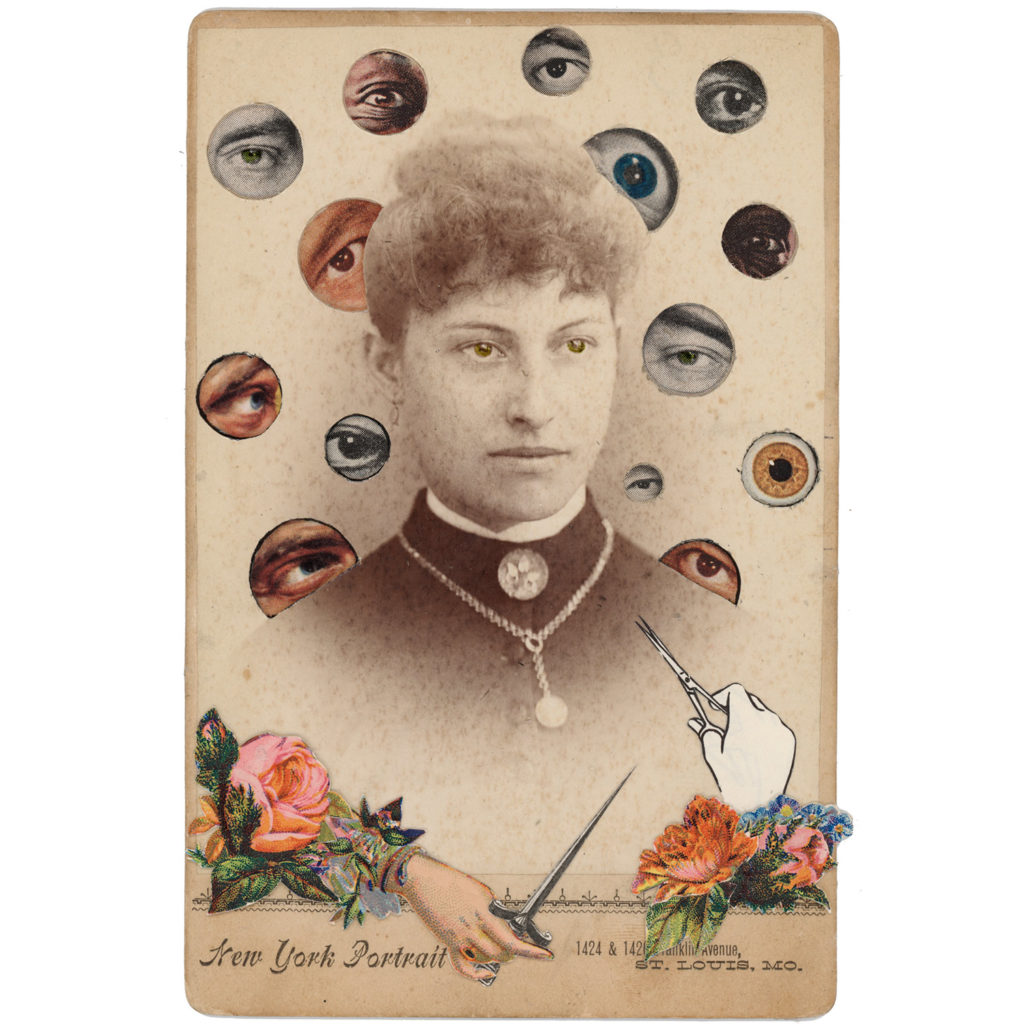

I think that ‘roadmap’ speaks to an early body of work. I was creating these mini monuments and imagining a kind of literal road map with ‘road trip’ ‘American Gods’ style road side attractions and monuments and memento mori. I used antique cabinet cards to create these imagined portraits of working class people that I found in antique malls and junk stores. I was very interested, and still am, with this thought of replacing was monuments and placards with ones that celebrate every day people teachers, nurses, carpenters, etc. The idea that every day people, the builders and do-ers that make this country run deserve to be lifted up and revered. I think it would have a more posititive community impact than a monument to someone who killed 100’s or thousands of people.

My work has expanded to include any sexy printed thing that I can get my hands on. I’ve been doing this for so long that I am fortunate to have people bring me back things from their travels to use in my work. I’ve been gifted some incredible French text books and medical books which have some incredible hand colored plates. I used several of these in Ariadne, Mistress of the Labyrinth.

Another constant theme I work with that fits into my roadmap of America is death and grief. Most of the work I made for a show called Palimpsest was a series of Vanitas portraits that spoke to that theme. Like the paintings they pay homage to, those pieces included symbols and imagery that spoke to the lifecycle and the nature of grieving and loss. I think we struggle to grieve properly in this country, and that the fear around the subject of death makes people very uncomfortable. I lost my father, my brother and my grandmother, within a few years of one another and I felt like as a person in my 20’s who had a job and rent to pay that there wasn’t really space for me to grieve properly. I’ve also learned through that process and therapy that there is no ‘right’ way to grieve. I can’t recall who wrote this, but it was very profound for me, that grief is something we carry with us at all times and that while we may recover from the emotional distress and deep pain at the loss of someone we loved so deeply and that the grief we carry is an expression of that love.

Collage on Cabinet Card

7x5in. 2019

TWS –Working with collage is always related with collecting. Can you tell us your relationship with the process of finding source material to work with? Also: it seems that you work with images taken from really old printed matter. How do you deal with the uniqueness of the original material and the need to destroy it in order to create something new?

I think my favorite part of the process is in the collecting of materials. I feel most at home in a chaotic junk shop or overstuffed Antique Mall hunting for collage material. I love the smell and feel of old books and magazines, flipping through each one is like a tiny time capsule. As it relates to collage and my process, by constantly working with original material it means I run out of or only have one of something rather than working digitally where scale and quantity are of little to no concern. It means that the work will always be changing and shifting and I hope that means it will remain fresh. I try not to treat materials as more or less precious than others, this can be difficult, but I no longer have to talk myself into cutting things up any longer. I’m an anti-archivist in that way, I want to dissect and rearrange.

Mixed Media Collage

3 x 5in. 2011

Mixed Media Collage

14-1/2 x 12. 2012

TWS –Can you tell us about the art scene in New Orleans? How has this been affected with the Covid outbreak?

The art scene in New Orleans has been very effected. I haven’t been to a gallery or museum since the lockdown. I am proud of all of the mutual aid and fundraising I see going on through various groups in town. Many artists and organizations shifted their focuses to serve the community. I spent most of the summer volunteering at a school in my neighborhood handing out food to folks in need. Prior to covid I would describe the art scene in New Orleans as vibrant and thriving. There are a number of artist run collective galleries that are constantly exhibiting work by local and national artists. I feel like the art community in New Orleans does a great job of supporting one another and really showing up.

TWS – Which is your own definition of collage?

For me collage is one of the most democratic art forms that exists. It costs little to nothing at all as a barrier for entry, all you need is a little imagination some printed matter scissors and glue. I think collage creates a vocabulary of imagery for artists which is why collage can never be monolithic. Every voice, every artist has their own relationship to their materials coupled with their vision and aesthetic which provides for endless possibilities with collage.

Find more about Michael Pajon’s work at his website or Instagram

Mixed Media Collage on Wood Panel

24 x 25in. 2018

Mixed Media Collage on Panel. 2018

Mixed Media Collage

14 x 12in. 2020

Mixed Media Collage

12 x 11in. 2020

Mixed media collage on antique cabinet card

7 x 5in. 2019

Collage

7 x 5in. 2019

Mixed Media collage on antique cabinet card

7 x 5in. 2018

Mixed Media Collage on Antique Book Cover

12 x 15in. 2014

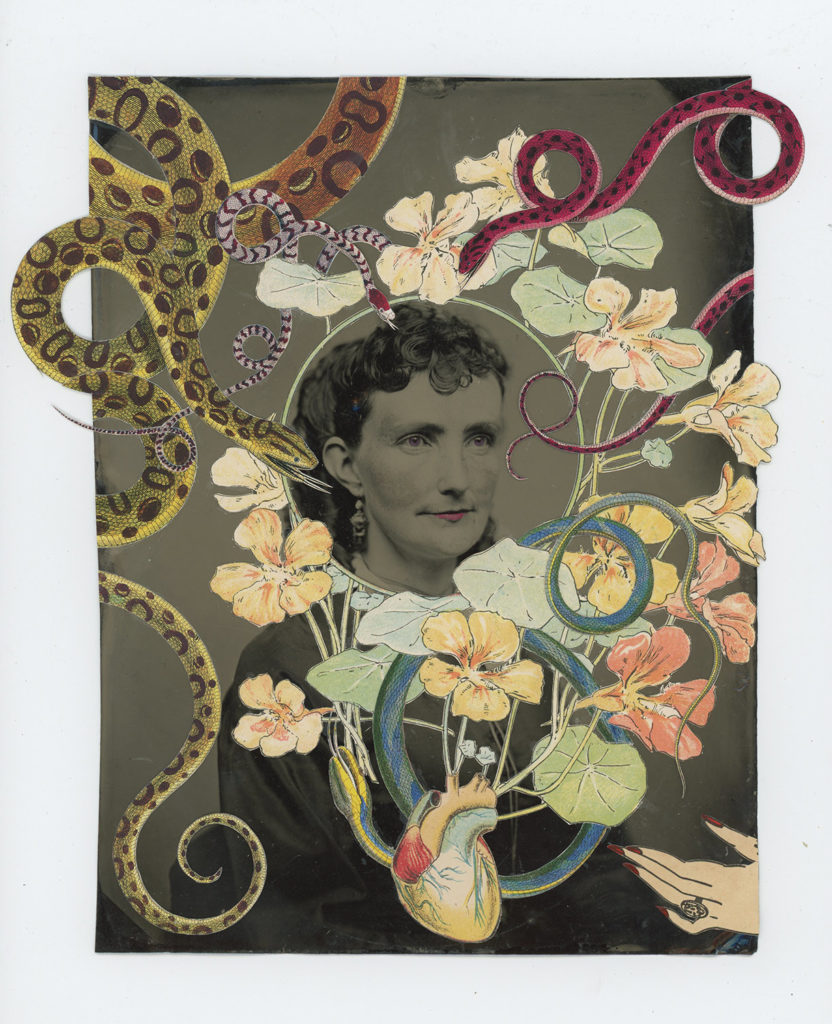

Collage on antique tintype

10 x 8in. 2020