Skip Brea (b. Bronx, New York) is a New Media Artist based in New York City who holds a BA in Studio Art and Literature from DePauw University and received his MFA at Florida State University. His paintings, animations, and installations examine the history of representation by transforming narratives and mediums with contemporary innovations. Brea is a distinguished recipient of numerous prizes and awards, his engagement with art history has led to several solo exhibitions across the United States while also gaining international recognition. In 2018 Brea won The Dean Collection St.Art Up Grant funded by Swizz Beatz & Alicia Keys, he was one of twenty chosen from around the world, one out of seven in America. In 2019 his work was commissioned by REVOLT, a corporation owned by Sean Diddy Combs, to be shown at the Black Summit in Atlanta, GA.

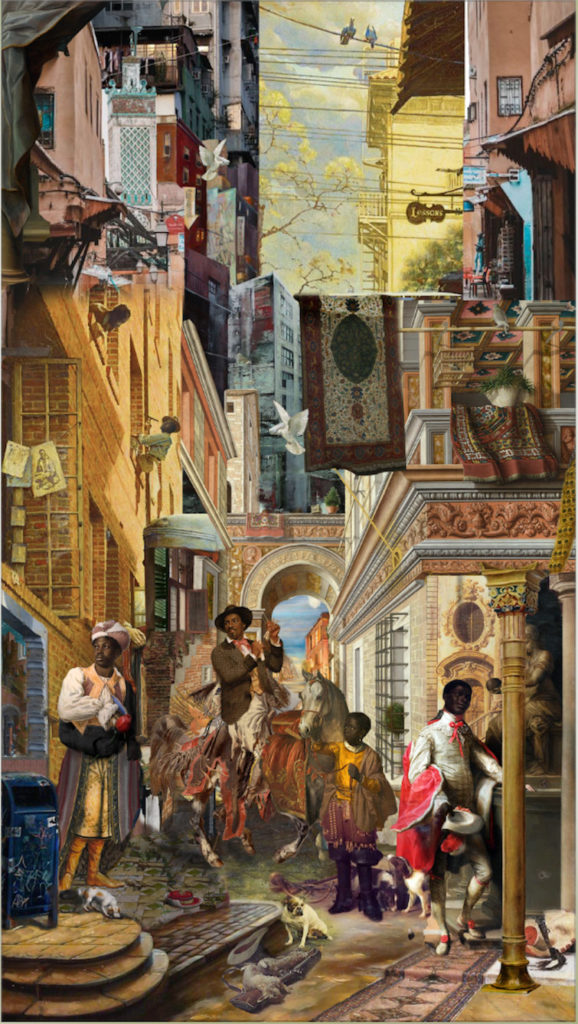

digital animation still (Detail Shot)

48 x 24 in

TWS –What led you to work in collage? Why do you think collage is relevant as a medium for you?

SB –I became fascinated with collage when I began researching the linguistics, semiotics, and perspective within cubism, specifically the syntagmatic chains and geometric substrates in how spaces and objects are composed and relate to one another. I began following the theory of syntagmatic chains throughout the history of paintings and cubist collages. I was already interested in the image, so discovering Michael Baxandall’s book, Patterns of Intention, (1985-7) became useful when I began thinking about how I use images in correlation to one another. When his theologies of the image within societal and mental constructs of culture related to my work, I started to understand where I stand in the chronological history of painting. I realized I could use my interest in these subjects and move them forward in time as pieces of visual information through the use of a contemporary medium. Baxandall had many critiques on artists and their conditions; how it affected their process and the assessment of history. His theologies truly motivated me when he was pushing the theory of painting to be understood as an expression of its time and place. This concern with the conditions under which a work of art is produced and consumed is what fascinated me the most.

According to Tony Buzan, an author and educator who has researched images and how they correlate with the brain, the brain always thinks through a visual pictorial response. Image-making and our perceptions serve as a way for us to make sense of the world. Through image perception and mind mapping, people create conceptualizations of their understanding of the world. In my practice, I am connecting the study of the historical canon of painting and what a cognitive response would look like through the use of image perception and collage. I am questioning and remodeling the history being presented in front of me both physically and theoretically and deconstructing and reconstructing what is deemed as visual history. I am challenging what is real versus what is artificial with synthesized versions of history. I collect pieces of history to collage into what may be considered as an artificial social structure; a metaphorical leap into multiple perspectives of historical viewership. This way of working undermines the canon by removing a single-point perspective, and observing it with a binocular point of view. Artistic activity serves as a form of reasoning and a way to think with the senses. This way of working is my reactionary response of compositing a painting that reflects on my initial experience with everything that has to do with that painting. A mental regurgitation happens where the narratives that are recreated are influenced by literature, poetry, and other cultural sources that may have been dismissed. My work is influenced by paintings from the 16th to the early 20th centuries, concentrating on moments where conditions like in-house slavery at the peak of white privilege, systematic racism, exoticism and exploitation of black and brown bodies. Furthermore, how art history follows instants all the way from the great migration to the great depression, as well as events post-WWl involving people of color playing second fiddle to the light.

This way of generating work catalyzes the imagination and explores novel possibilities as part of the creative process. I use this to my advantage because I am not interested in the literal, realistic truth, but emotional, atmospheric truth. Studying the environments of the artists that I pull from allow for influences to leak into my practice, and the medium of painting allows for my use of new media to be the constant reminder that I am still experiencing the past through a present-day lens and format. Through my extensive research of the canon I’ve touched on topics that begin at the start of the diaspora and end at orientalist paintings. I engage with specific themes such as Euro-American Art & The Image of the Black in the Western Canon, more clearly migration and chronology of history that comes with it. My reasoning for the use of technology and the inferring of cubism with its relation to collage is how I decided I would like to place myself within the conversation of the history of painting and new media simultaneously. If we were to take those two terms (Painting and New Media) and themes within them (Collage and Cubism) coupled with these theories (Deconstructionism & Image Appropriation) and intertwine them with my own ideologies (Artificial Reconstruction), we’d get what I find to represent my work and this thesis, that is: “Artificial Cubism.” Artificial Cubism is the hybridization of traditional old master paintings with a sensibility informed by images produced through a means of technology. This term will come to unify how I came about joining the conversation of all types of art historical narratives and predecessors. Artificial Cubism paved the way for my choice of artistic influences, not as a means to deconstruct and demean the values put forth in front of me, but rather, shift the focus to a more inclusive conversation through the use of their subjects and our history moving forward.

digital animation still (Detail Shot)

48 x 24 in

2020

TWS –Your paintings series deal with the history of representation. Can you expand on this, please? & Can you walk us through your work process?

SB –My works examine the sadistic entanglements that make up our visual culture, language, and world history. By using a combination of digital illustration and painting tools, I weave, stitch, and mesh together paintings of our past that precede copyright laws with pieces of contemporary information to create a new unified image. Similar to sampling in music, I take a section of one painting and metamorphosize it into a greater idea with parts of other paintings. At first, the spatial cohesion in the painting maintains an illusion of conventional space, yet the composition is intended to break apart under scrutiny. In many of the paintings I source from, the images of people of color are described in an unfortunate event or positioned as the undermined figures in the painting. While deconstructing these historical paintings, I pick out these subjects and create scenarios and portraits of them as the main focus of the compositions. The figures then become symbols of a dismissed culture and a time period providing a foil to my retelling of their fiction which elevates them into further conversation. The use of new media technologies and digital collage allow me to create a narrative formatted to our time. By manipulating and transplanting the original figure and space, I reclaim and transform the significance of what these subjects now mean. Removing them from their original compositions gives me the ability to recontextualize their future.

Rather than simply exposing the position of the figure, I deconstruct the painting’s structure of power with digital tools, allowing both the medium and the subject to exist in a new light. For example, take the well-known painting Bain turc ou Bain maure (deux femmes) (Turkish Bath or Moorish Bath (Two Women)) by Jean-Léon Gérôme, in which there is a black woman nude from the waist up bathing a white nude woman facing away from the viewer. I remove and reinsert the black woman into an entire new composition, and redress her within that same position doing something else

A clear-cut example that I have used in my work would be Three Boys by Bortolome Esteban Murillo. The painting portrays a young black boy being denied food by two young white boys as he carries a jug of water on his shoulder. I wanted my rendition of him alluding to the idea of fruitfulness and inclusivity, a helping hand as he may have something to offer, so the jug became a symbol of togetherness, a part of something bigger than denial, the opposite of rejection. You can see this in my painting Manifest Your Destiny, 2020. My personal collection has over hundreds of documented images of paintings and photographs that contain a wide range of subject matter surrounding people of color. As I’m searching through these archival works of art I am extremely tentative of what some may deem as insignificant, because that is what I may deem as both purposeful and worthy. Elements such as divisions of socio-economic class, racial discrepancies, political miscalls, geographical exploitation pre-and post-slavery, as well as domestic servitude.

digital animation still (Detail Shot)

48 x 24 in

2020

TWS –There’s a mix of very classic art and contemporary culture. Can you tell us what’s in that mix that interests you?

SB –As time passed my theories of the work allowed room for evolution not just compositionally but materialistically as well – from the painting and collage aspects into more of a new media framework with similar conceptual wiring. Bringing up the question, how can I continue to use this idealistic thread of time to manipulate the physical form in the way it’s presented. More clearly, in an installation, how can I rewire the way it’s presented to the public while still maintaining the illusion of a painting. For example, I’ve used the literal canvas as a gimmick to be the signifier for the image, therefore, connecting the past with the future, reinserting a different viewpoint of the same narrative, holding the good and bad historical references up to the light that is the canon of painting. If I’m not deploying the paintings into a physical form, printed stretched and framed, I am using other methods of manipulation such as animation and videography to create a sense of atmospheric energy.

My multi-ethnic background rooted in Spanish and Dominican culture has opened my eyes to a diverse range of personal experiences. I identify as a person of color as it encompasses all of my identities together. I use my multi-cultured history as a focal point of interception. Collage is my interception point between the way I perceive and mentally bring pieces of information together. It allows the ability to mold messages that could create conversations about all these pieces of visual information. Everything that I had acquired while researching image correlations and the image of the black and brown identifier within an art historical context had turned into a database. I wanted to further explore what happens when an artist translates certain sections of a painting and intertwines it with others. What happens to the subject matter and how does it affect a contemporary space using a medium that is of today’s time. Moreover, how does this way of working influence meaning and the interpretation of these images?

My painting The Bronze Legacy, 2020 displays a family showing all men as they are entrenched between two worlds, the architecture engulfs them within the center of the composition. This work of art is a good example of how my way of working is both additive and subtractive just like painting in the traditional sense. The reoccurring additive process was physically altering the canvas and its frame, this time I used the historical tradition of gold-leafing on the screen frame as bordering material, which alluded to the historical pursuit of gold by many Caribbean ancestries to pay tribute to both histories of the Caribbean and painting. Whereas, the reoccurring subtractive process was done through technology, where image handling and pixel control were manipulated with careful modular thought and strategic arrangement.

digital animation still (Detail Shot)

24 x 48 in

2020

TWS –Your work is very related to technology. Can you please expand on that?

SB –When it comes to assessing the transformation and advancement of my work, usually one of the first names that arise is Walter Benjamin and his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, (1936). According to Benjamin, a work of art has always been reproducible. He contends that things that are man-made could always be imitated by man or woman, but a mechanical reproduction of a work of art advanced enough by two procedures that technically follow reproductions of a work, intermittently, cannot be copied. Benjamin’s prominent claim is that the difference between originality and reproduction is its presence in time and space; furthermore, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be. The unique existence is what allows the work to retain its full authority in the face of reproduction. This was important for me because it removed the theology of the artist’s hand and introduced to me the idea of mechanical reproduction in replacement of the artist’s hand. Creating codices of information that cannot be duplicated but instead creates a bridge between technological authenticity and the artist’s hand.

My struggle with choosing a medium led to my stylistic way of operating. For example, If I had to get technical: I’m a digital artist, who works within the collage, graphics, photography, video, and animation. Nevertheless, I began as a painter, which is where I get a lot of my historical references and source material from. The idea behind a façade has always been an attraction. Making the viewer uncomfortable or intrigued materialistically is something that conveniently shows up in my work. Being confused and uncertain around such concepts is not a sign of weakness or ignorance. It is to Derrida what it is for myself, the central mark of maturity. The tactic is to glamorize this condition and to give it a positive ring, which is why he used such a keen Greek word like aporia, which means puzzlement—a cubist double entendre. He was proposing aporia as a state we should feel proud to know and to visit regularly.

Making art work that looks like it is stuck in-between different worlds is a reflection of not just myself but the world we live in. According to the dictionary, the definition refers to the in-between as a person place or thing that is between extremes, or contrasting conditions. I enjoy working with the in-between because it leaves an enormous room for materialistic ambiguity. For example, is it a picture or a collage, a painting or a canvas print, a screenshot or a video? This confusion could be a mirrored reflection in how I received this visual history at first: a recreation of this fascinating but yet questionable moment. This is where collage becomes useful because it is resonant, and usually made of the stuff we see every day or that we have seen before; therefore, it holds a sense of the familiar so it reflects our reality. To put it more clearly, it is universal, it doesn’t discriminate, it liberates confinement while creating something new out of the old. Appropriation, appreciation, and homage could all go hand in hand. In a sense, whether the results may be positive or negative, a critical analysis of the world and its theologies are being made. Those three terms have laid a foundation for many of my compositions creating relatable narratives for people of color to dive in and possibly see themselves in, or at least have the option to do so.

Marshall McLuhan, in his essay called: The Medium is the Message (1967) predicts the rising of the internet before the internet even existed. The text allowed me to discover my place within the world of art in the context of technology, and not just throughout the historical canon of painting. I learned how I could use technology as a tool for research and quickly become a historical search engine through the use of images and how I could relay a message through this medium. In this essay, McLuhan adopts the term “message” to denote the effect each medium has on the human sensorium, taking inventory of the “effects” of numerous media in terms of how they “message” the sensorium. The essay made me question how I physically chose to display my work. The numerous years of returning to the text permitted me to think of mediums in multiple ways, from the printed canvas evolving to screens and projections. The canvas can be stretched and framed, displayed like an actual painting; once again, allowing me to change the context, but the duplicitous screen became this ambivalent medium that was capable of contemporary transformation. Through this text a movement from still images on a canvas to a minimal amount of movement on the screen was made.

Digital Collage on Archival Giclee

28 x 34 in

TWS –Inequity for the black community has a long story in the US (and the world). Have you felt this inequity in your experience in the art world?

SB –American art critic Donald Kuspit has two texts that have been anodyne in my way of thinking about disassembling whiteness in paintings and working in response to erasure or disempowerment of brown and black bodies within the canon, literally re-centering brown and black bodies on the canvas-dismantling and reconstructing compositions to be shown from a new perspective. The End of Art (2004) and Collage: The Organizing Principle of Art in The Age of The Relativity of Art (2007) are pieces of writing that best exemplify ideas surrounding appropriation, appreciation, and homage. Kuspit minimalizes it to the idea of paying tribute to those who come before, as he introduces his theory of the New Old Masters. Personally, it is the staple attainment for a new up and coming artist like myself. Kuspit describes it as:

“Bringing together spirituality, humanism, innovation, critically, and having a complete master of their craft. For them, art is both conceptual and material. Their art is aesthetically resonant and visionary. They transfigure the unhealthy ugly into the aesthetically satisfying, stripping ugliness of its social and metaphysical overlay and letting irrationality ‘stand forth in all its inevitability.’ The New Old Masters bring a new harmony out of the tragedy of life.”

Collage creates a path to becoming a “New Old Master” because it falls right in line with cubism. There were only two types of cubism, synthetic and analytic. Analytical Cubism is the early phase of cubism that ran between about 1908-1912 and was mostly practiced by early Picasso and Braque. This form of cubism is simpler, using a wide range of mostly dark colors and working with overlapping layers. I would say it was all about the fusion of color and shape that was critically thought out. The artists would study (analyze) an object and then break it up into different blocks and pieces, and assemble them in different visual angles and literal viewpoints.

Synthetic Cubism grew out of analytic cubism a year later. It was pushed by Picasso because he deemed to coin himself the founder of the movement. In comparison to analytical cubism, this style developed through the construction process, rather than the analytical process. A lot of the works tend to look like collages. Artists like Picasso and Braque began using a wider range of materials, textures and brighter colors into the paintings to create dimension. The artist would often use newspapers, colored papers and more, to represent the different layers of the object. The lines became simpler and clearer; however, the reality was still twisted with a lot of usage of different viewpoints and angles.

The study of cubism later led to George Condo a contemporary artist that has made an immense influence in my way of thinking about terms within the cubist movement. Condo coined the term Artificial Realism, “the realistic representation of that which is artificial,” to describe his hybridization of traditional European Old Master painting with a sensibility informed by American Pop. Condo pays homage to Picasso to an almost obsessive degree, and he coined the phrases “psychological cubism” and “artificial realism” to describe his work. “Picasso painted a violin from four different perspectives at one time,” Condo said. “I do the same with psychological states.”

Once again, if we were to take those three terms: synthetic cubism, analytical cubism, and artificial realism and synthesize their ideologies, we’d get what I find to represent my work, which is: “Artificial Cubism”. Artificial cubism is the hybridization of traditional old master paintings with a sensibility informed by images produced through a means of technology. Artificial is defined as made or produced by human beings rather than occurring naturally, typically as a copy of something natural, in my case creating a double entendre on the pretense that is “artist’s hand”.

Cubism has multiple faces it can wear, those that carry many characteristics of collage and visual perception. Picasso studied different angles and color of objects and George Condo studied the different psychological states within portraiture through line-work and shape. I use technology to study and analyze the digital image, collage multiple images together, and manipulate one image until it’s rendered obsolete. This includes several ways of layering, creating transparencies and opacities to further investigate the space and figure, as well as the artist’s past psychological state via time and place. Once again, Artificial Cubism paved my idealistic notions, not as a means to deconstruct and demean values, but rather, to shift focus towards inclusivity. The artists that came before me play a huge role in the way of thinking about the context of time and subject matter. Compositionally, an artist like Salvador Dali and Hieronymus Bosch reflect the way I make subjects in my paintings surreal and break away from what the public may deem as a traditional oil painting. When it comes to mixing and matching fabrics and positions, I turn to some of the Spanish old masters like Diego Velasquez, Francisco Goya, and El Greco. George Condo said, “The only way for me to feel the difference between every other artist and me is to use every artist to become me.” Since all of these cultures and styles come into play within the work, they inevitably begin conversing with one another, making the spaces and subjects a reconstruction study of deconstructed histories and lineages.

Digital Collage on Archival Giclee

28 x 34

TWS –How do you feel things have changed since the massive BLM protests and movement 2020 has seen?

SB –I think that it was a huge shift especially with the pandemic, everybody was stuck inside with a lot of news and social media and nothing really to distract them because everyone was locked inside. There was nowhere to go and attempt to ignore what was happening.

I believe this is how artists and a lot of people find their voices unfortunately these lengths are some of the breaking points to make a lot of people wake up and be a change for the world. I went to college 2012 when Trayvon Martin died, I came back to New York and my art shifted to create a voice after the BLM protest in 2014 due to the unfortunate deaths of Michael Brown Jr, Eric Garner, Ezell Ford, Tamir Rice, those names will forever be embedded in my memory because it was at that moment that I knew I had to use what I have in order to create a voice and stories for the future.

Titus Kaphar, a contemporary counterpart I truly admire, has always been fascinated by histories of all kinds – how history is written, recorded, distorted, exploited, displayed, reimagined, and understood. In Kaphar’s work, he explores the physical materiality of reconstructive history. He often borrows from the historical canon through painting and sculpture, then alters the work in some way. Kaphar keenly addresses power structures of whiteness within western paintings, as well as race dynamics throughout the histories in the academic curriculum. In doing so, he aims to perform what he critiques as a revealing of something that has been lost and to investigate the power of a rewritten history. Being such a huge influence, my creative process evolved into making connections, considering relationships, continuing a thread of old imagery, and moving them forward into a more familiar narrative. This divergent way of thinking was critical to the evolution of my work.

Early in my career, my influences were mostly white Europeans because that is what is taught in art history due racism, white supremacist ideologies, whiteness in academia and western art, a historic erasure and devaluing of artists of color and non-western artists, and lack of diversity in authors, curators, and faculty. However, this is changing, many institutions and faculty are fighting to bring artists of color and non-western artists into art and art history courses. With all of this research and art work I am attempting to attach myself to the tail end of the conversation and I can’t make a comment without first revisiting the root of where everything started. Despite my compositional and historical influences, there have been artists of color who have influenced my way of looking and reading into these paintings and histories. Conclusively, these characters, subjects and moments that were pulled from our history books and in our museums, should be something we know about but we don’t because of the preferential focus that art history has shown us. In my creations, I attempt to find a sense of reality in the falsehood of collected images, hopefully, allowing for the creativity to force a realization of our real history and its relationship to the canon of painting. I want viewers to ultimately see the subjects I pulled and compositions I created as keeping what society tends to discard as alive, let it provide a cautionary tale for your own values and morals. Go back into the history books and take a look, assess for yourself what you’d like to get out of a viewing experience and a historical regurgitation of a time and place for the future to come. Finding meaning and significance in what creates our history shapes our future. I will forever keep this in mind. When speaking to my mentor Carrie Ann Baade about her own work she observed and mentioned words I won’t ever forget: “Finally, the image that has the function of being overly pedantic is too utilitarian for the desirable effect of having the viewer return to an image over and over again without ever being able to thoroughly consume its meaning. The challenge laid before me is to mean more and more, without meaning less.” Agreeing with these sentiments wholeheartedly, I aim to create more meaning all while reflecting and growing from what has come before me.

digital animation still (Detail Shot)

48 x 24 in

2020

TWS –You classify your work in two categories: Paintings and Graphics. How are they different? What do you look for in each one of them?

SB –I’m still struggling with how to talk about both in tandem with one another as I still think of them as two different entities, I guess it’s my intellectual side not siding with my more free creative side. As some may see different worlds in Graphic Arts & Fine Arts. I love them both and use my skills in both in very similar fashion; they just tend to manifest in very different ways. Out of collage came about a voice, I found my place and my focal point of understanding the world, graphic design gave me the ability to do so without the means to do it physically. I have been fortunate to learn the ways to manipulate the medium in all forms and that I am grateful for. As for working in two styles, the best part about being an Artist whose into the Graphic Design World and the Fine Art world is being able to collaborate with the museum one day and with a fashion brand the next right ?

TWS –Lastly, here’s the questions we ask all artists interviewed: What’s your personal definition of collage?

SB –God’s way of uniting the universe.

Find more about Skip Brea at his website or Instagram

Digital Collage on Archival Giclee Print (Unstretched)

46 x 36 in

Digital Collage on Archival Giclee

28 x 34 in

Digital Collage on Archival Giclee

28 x 34 in

Digital Collage on Archival Giclee

28 x 34 in

Digital Collage on Archival Giclee

28 x 34 in