Interview: Andrea Burgay

Michael Oatman is an artist and curator living in Troy, NY, where he teaches in the School of Architecture at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. For 30 years his large-scale collages and installations have been shown internationally. Calling his practice ‘the poetic interpretation of documents,’ he has critically re-presented private and institutional holdings of material culture. As the first artist invited to interpret the personal archives of the astronaut, Oatman exhibited “My Father, Neil Armstrong, My Mother, The Moon,” at Purdue University’s Museum in 2018. His works are held by MASSMoCA, The Tang Museum, MoMA, and numerous private and public collections. Oatman received the Nancy Graves Prize in 2003.

An Origin Story

AB: How and when were you were first drawn to collage?

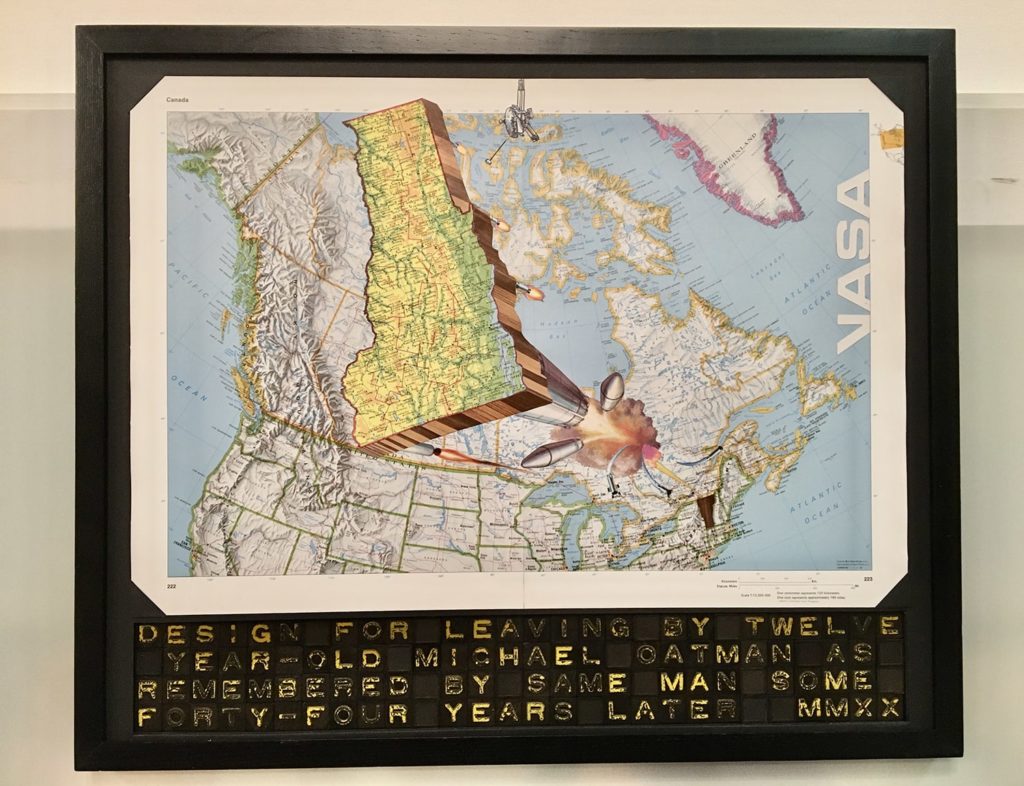

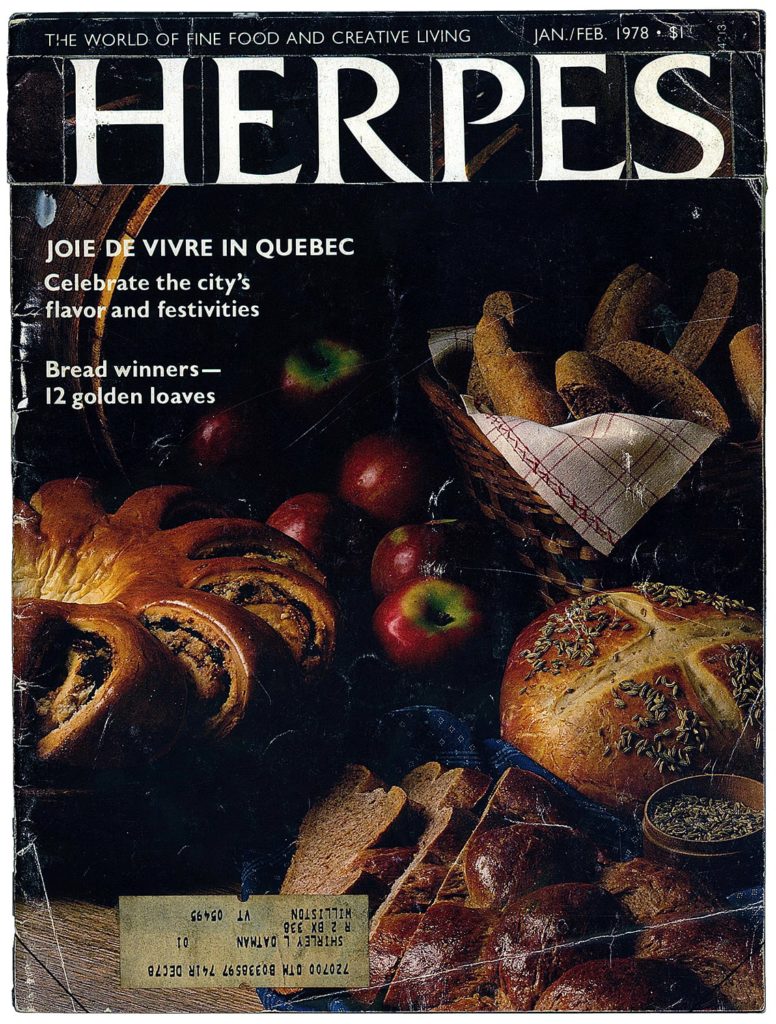

MO: I was drawn to it at a pretty young age before I knew the medium had a name. My first collages were props for movies that I made in high-school. In fact, they were magazines that I remixed to be these background, kind of funny images. People would be reading magazines in the dentist’s office, and instead of TIME, it would be EMIT. Or probably the funniest one was Herpes magazine, which was remixed from a cooking magazine called Sphere that my mom subscribed to. The one I used had these big brioches on the cover that looked a little medical.

In these goofy Super 8 films, which were very skit based, I made props out of these magazines. I made the films with a friend named Mike Lawes, who I don’t think would call himself an artist, but he’s one of the earliest uber-consumers of pop-culture that I knew. We knew each other in the 8th grade and Mike was a big music buff. We had a love of certain artists like Miles Davis, Santana, and artists around jazz-fusion and rock, like Weather Report. Looking back, so many of the artists that we were interested in had a kind of collage approach to making music—early pre-sampling culture and big narratives that were strung through these concept albums. There was certainly a lot there for some teenage boys to talk about in terms of, whoa, what does that mean?! Not to mention all the pop and the punk of the era.

I remember my first real collages as being associated and support media for the films. Maybe at that time I still thought that collage was less creative than being able to draw something with precision, which I think, seemed to be the benchmark in grade school for being an artist.

The most influential things I was doing were with another friend, Joe Keyser, who was the first real collector I knew. In 7th and 8th grade, Joe introduced me to stamp collecting. He collected currency. He was into music by Brian Eno, collecting all the EG albums. He clipped out these political cartoons which he asked me to copy and draw and eventually we made a kind of collage collaboration.

As a stamp collector, he was really interested in first day of issue covers. When a new stamp came out, like Skylab, there might be an envelope put out by the US Postal Service with a drawing of Skylab on it.

Joe would assign me to draw subjects for stamps that he already had. So I would do a first day of issue cover for a baseball player stamp that he had, or a stamp of a steam-engine. I would go to the library and look up some other steam-engines, and then draw them on the envelope. We would go to the post office with this drawing that I made, on an envelope with a stamp on it that was way out of date, and then we would get it cancelled. It was kind of like a double artifact—a stamp and an artistic drawing on a weird source of paper, an envelope.

There was a collage sensibility about that which I think for us resulted in some sort of officialness, an official act that we were participating in—in commerce, commemoration and history. I think that was a deeply informative experience for me in terms of the nature of collage.

That was bringing together things that were more alike than not alike, but I think that the not alike thing was a third person, a stranger, a postmaster with a cancellation stamp that would bring a mark into play. And we didn’t know exactly what the mark would be, although we knew it would have the date on it, which was another thing that seemed somehow important. Our gesture had been seen that day by another person, and witnessed, like a notary public.

Over the years I’ve thought back about your very question, what were those first things? And the truth was that there were simultaneous things that all swim around in my head now as the origin of my interest in collage. I wouldn’t say that it was with a consciousness of these as collage, I think it was the act of finding, remaking and, for lack of a better term, putting a stake in the ground about “this” being your mark.

Aesthetics and Collecting

Joe also introduced me to beer can collecting and I became an avid collector. It was my first real encounter with aesthetics in any sophisticated way and I still have the 3000 cans that I collected during our friendship. It was a thrill because we would not only find the cans of the beer that our parents brought home, but when Vermont was the first or second state to introduce the 5 cent deposit, you could go to redemption places nearby and the guys who were working in this smelly beer environment, recycling cans, would routinely pull out odd ones, foreign ones, ones that didn’t have the 5 cent return on them. So you would go in and there would be like 200 cans along the top ledge. I think, in that competitive, inquisitive way, if you saw ones that you didn’t have, you said, hey, could you save a Stroh’s for me if that comes in? Or a Yuengling? Or a Billy Beer, the brand brewed by F.X. Matt’s for President Carter’s brother.

The other way that we found cans was the first times I was technically trespassing, going into abandoned buildings. We would visit Joe’s dad in Montpelier, Vermont, and I remember going into buildings that had been long vacant and Joe showed me how to look in-between the walls, particularly the walls on the top floors where workers would throw beer cans between the studs. And we would open them up and find cans. Sometimes five would come tumbling out!

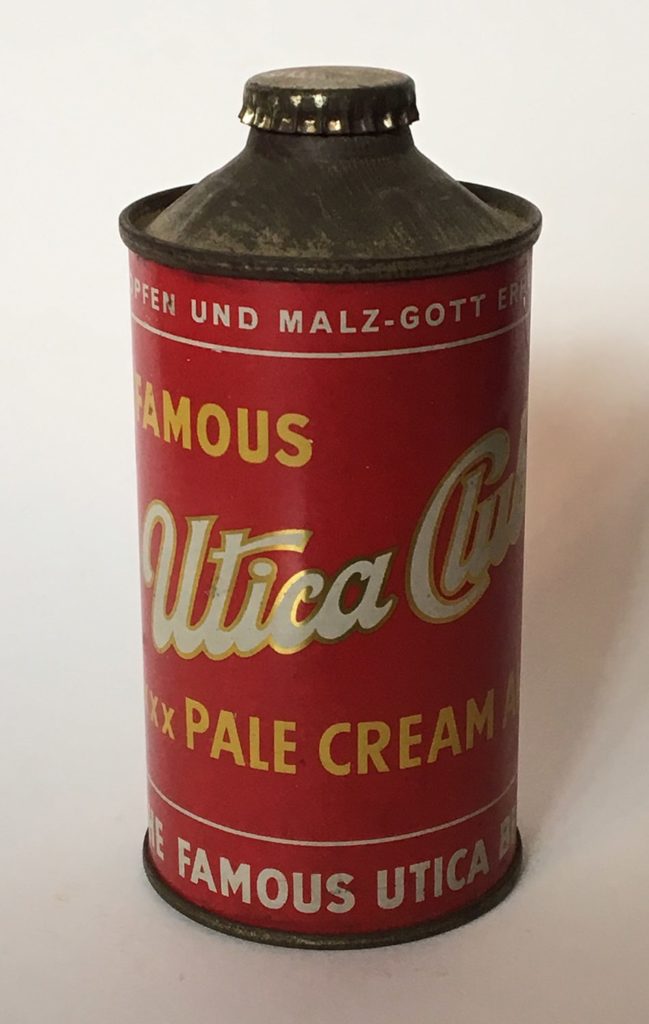

This is the best one I ever found. It’s pretty great. This is a Utica Club cone-top.

As you turn it around, you see these little inset pictures: a bell-hop or porter with some beers. You see this vertical advertising of the brand of the can company—Cap Sealed. You see the metal seam and some promotional language.

I like talking about this can because I probably found it in the 8th grade, and I really was wondering about the design decisions: to put this edge in gold, the typefaces—this kind of elegant one which seemed old world and then this very 20th century one. This also was the origin of my interest in the backs of things, particularly products, because that obviously gets designed and is not an afterthought. There’s a great deal of information there. I always think about the beer can collection as my first introduction to aesthetics in any way where it felt like, I figured that out.

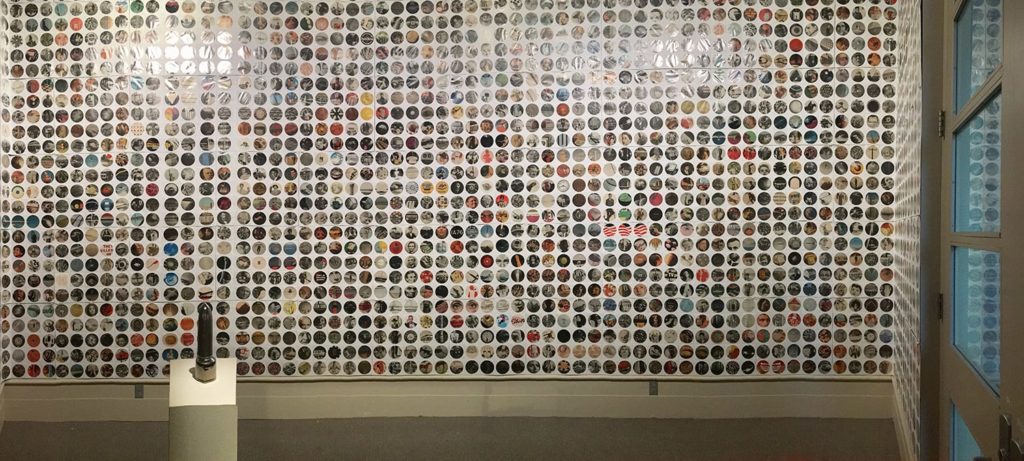

And when you have 3000 cans on the wall next to each other, it’s like instant collage. You think you’re organizing something taxonomic, putting them in alphabetical order, or by region. I remember reorganizing my cans by size and by color. But in the end, if you’ve got rows and rows, what’s really confrontational is that there’s this collision of images. We would also go to dumps and find cans, so there was this archeological aspect of collage, of looking for source material. In this case I wasn’t thinking of it as source material, but looking for material culture.

I found this one standing up under the rafters in a building in Montpelier, Vermont with a little shaft of light on it. Joe had been collecting cans for several years, and I was a total novice, and I found the greatest example that we had ever found together. It was a kind of trophy, and proof that it wasn’t really about having them all, it was about finding them. Which has been a very strong sensation that has stayed with me ever since. Maybe the most important aspect of being an artist for me is finding stuff.

The Evolution of a Practice

AB: How do you describe your work now?

MO: The “now” is a kind of weird concept in the work because I feel like it’s always been a continuum from a certain point. Maybe from those films in high school, which were about comedy, playing with language, copying things, but doing some totally original bits too.

I would say that my work has long been very conscious about language. The shorthand for my work is, it’s basically poetic reconfiguration of archives. So that’s the central theme. Then I would also surround it with the satellite ideas of humor, both visual puns and remixes, and also, through titling, a kind of linguistic humor. Lately, I’ve been thinking about my work as low-narrative, or non-narrative, but extremely pictorial.

I had always made collage ever since my freshman year at RISD, but it came and went. It was also subservient, like in those early films. I made collages that would become paintings. I would make a little thing, and then I would blow it up. It was a Rosenquist sort of operation.

Towards Installation

I think that the most pivotal work that I made as an undergraduate was called Study for a Camping Trip. It was a painting of two figures in mummy sleeping bags. Big, I think, 8 feet square. Coming off the painting was a tent canopy anchored into wooden boxes filled with grass that I’d grown. Behind each painting was a speaker that played an audio track that I cobbled together out of samples that I was making, using the little Yamaha 4-track machine.

So I had made a painting with sound, in the format of an environment, in a room with a single big spotlight. I didn’t know that that was an installation, but it was one of the first things that I had ever made where I felt like, I haven’t seen anything like this, and I’m not really sure why I made it. But looking back, it was an installation, with its roots in assemblage, painting and sound art. It asks something different of the viewer. It wasn’t walking up to a painting on the wall. You had to go under the canopy. You had to listen to the looping sounds of crickets.

The title was related to the way the figures were made. They were two figures in a sleeping bag, but they looked like they had been through some kind of unnatural event, like an atomic bomb going off. Study for a Camping Trip was a very bad idea, this situation that they found themselves in. I did a lot of studies to figure out the sleeping bag figures, and I ended up working into the surface with an acetylene torch laying smoke into plastic and wax. It was a very collage project. But I didn’t have any language for it at the time.

AB: It sounds like that piece has a lot of the roots that you worked from since then.

MO: I think you’re right; it was the DNA of the future installation practice. Even though I still made paintings for a decade, it was the beginning of the end of my painting.

Under the Influence

I was working in a variety of mediums my senior year. I had this facility and all these things that I was working on, but it was wildly divergent. I always say that when I had found Max Ernst’s work, it was a huge relief for me because here was a guy who played around in tons of different mediums. Most of my peers in the painting department then—Jeff Quinn, Heidi von Conta (Howard), who are in the Cut Me Up issue; a painter named Geoff Rockwell who’s an amazing artist—all of them were making very consistent works, they were making bodies of work that hung together.

To this day I remember going into Geoff Rockwell’s studio and there were 25 paintings of a lobster boat on the ocean, on fire. Little ones, big ones! He had them leaning on easels, it was almost an installation in itself. He had just been obsessively painting this lobster boat on fire. And if it was just the lobster boat, it would have been interesting enough, but the fact that it was on fire seemed very important to me. And the fact that there were 25 of them seemed like there was a mystery here.

I identified in that room of 25 boat paintings a sort of ripple in the time-space-continuum. I mean you walk into a room and you see a painting, and you see it being worked on by an artist, that’s one thing. But then you see all this production and how they’re thinking about it…

So encountering Geoff’s studio, which was like a real painter’s studio, and then something happening that I don’t even think he was aware of, this kind of autobiographical painting environment, was very moving for me. That’s one of many images I’ve kept in my head from my undergraduate career as a painter and a printmaker, and I’m sure that that influenced Study for a Camping Trip on some level.

I didn’t plan on talking about this today, this encounter with Geoff’s work, but I was very lucky to have a bunch of peers who were amazing painters. I think it wasn’t the painting that appealed to me, it was going into 20 studios and seeing this disparate production, and then going back to my studio and seeing 20 different directions and feeling like, oh man, I’m really lost.

Exploring Concepts, not Mediums

When I made the leap from being a painter to being an artist who figures out the best path to express an idea, I realized that that was what was happening to me while I was a painter. I was restless and indecisive and trying a lot of things. So there was no consistent product there, and that can be its own trap too. I’ve learned later in life, falling into making something that is recognizable as yours and yours only is really appealing and really dangerous. I think that we need to find our voice and then periodically take singing lessons along the way.

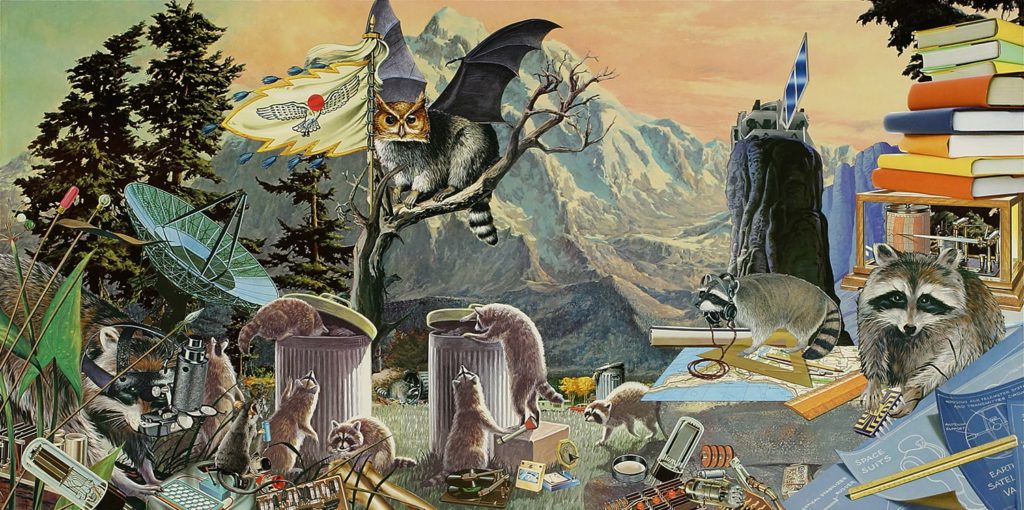

So the poetic interpretation of documents is the core idea with the collages and the installations. There is also a deep consideration of the encounter that the viewer has with the scale of a work, the complexity of it, the topicality of it, or even topics from different eras slamming into each other.

I was slowly beginning to become very interested in how being trained as a painter and doing things like setting up still lifes and painting them, that I could be doing that in room spaces, and not painting them. Creating a kind of theatrical setting, which is what the installations became. After a time, I began to refer to these installations as “unvironments,” or “still films.” I finally settled on “maximum collages,” which is how I now refer to both my images and architectural works.

My process has always seemed to move over one step, medium-wise, from whatever I’m doing. I make environments through the lens of a painter. I make video through the form of sculptural objects; I’m always thinking of drawing in terms of cinema. So it’s like, there’s always a filter that I think has prevented me from really becoming a painter, sculptor, installation artist or video artist. There’s this pursuit of not so much what mediums can deliver, but critically thinking about those mediums, and why people are so insistent, both as viewers and makers, on identifying with these mediums.

As a younger artist I was very moved by the work of an artist named Sam Cady. I realized that certain of Sam’s large shaped-canvas paintings were him sharing his experience with the viewer as directly as he could. He couldn’t lead you there by the hand and say, see this amazing thing that I found. But I found increasingly that I could, and that’s what I wanted to do. My process of finding was so exciting, and often so uncanny and strange, that if I could take every viewer and hand them this book that I found, or if they could come with me when I stumbled across a cult in the middle of the woods, that was something that I could retell in a spatial situation.

Why Collage?

The plasticity of collage as a material concept, as a construct intellectually, and as a trigger for how I communicate some of the sensations of an experience to the viewer really coalesced eventually in installation. Sometimes they had sounds, video and smells, sometimes they had physical limits and opportunities. In a lot of my artwork, the viewer can touch stuff, sit down, and open drawers up, for example. I hadn’t seen that much at museums, except at children’s museums, or the occasional science museum, which were all places that I loved.

So collage has become my savior in terms of a thing that I can return to that I can take in almost any direction. I’m making collage when I’m editing a movie, I’m making collage when I’m making an installation, when I sometimes attempt sculpture, I’m doing it. Even the drawing process is often about bringing things together that are never in front of me.

Process Changes Product, or, On the Value of Archives

AB: In addition to sorting physical materials to make your installations and collages, you weave references from history, art history, film and your personal biography into your works. It sounds like what you’re talking about is that you recreate a specific experience in each work—is that how the selection of specific references comes about?

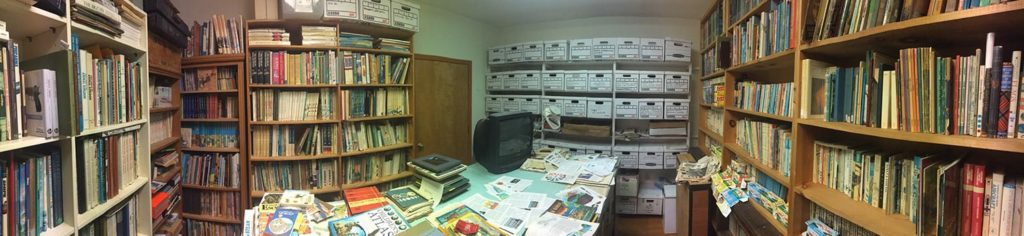

MO: I think that the mechanics of it ended up being my archive as the deepest part of my process. There were other important tools along the way. I think of the archive as my greatest tool. And the X-Acto knife. And the pick-up truck. And the ability to take-off and wander. I would say that also it might take me a decade to use something. So the other big tool is forgetting —and finding stuff again. To know that I’ve really found something and bought it for a very specific reason.

I think that over time you learn how to reuse your archive, you learn how to re-see it. I very much had blinders on for the first 20 years of the archive. I would take apart a LIFE magazine and put all the images I didn’t want into a banker’s box and I think I wound up with something like 20,000 rejected pages of photographs, of text and graphics. I recently reused all that stuff in a big project called Imitation of Life, or, the Fossil Record.

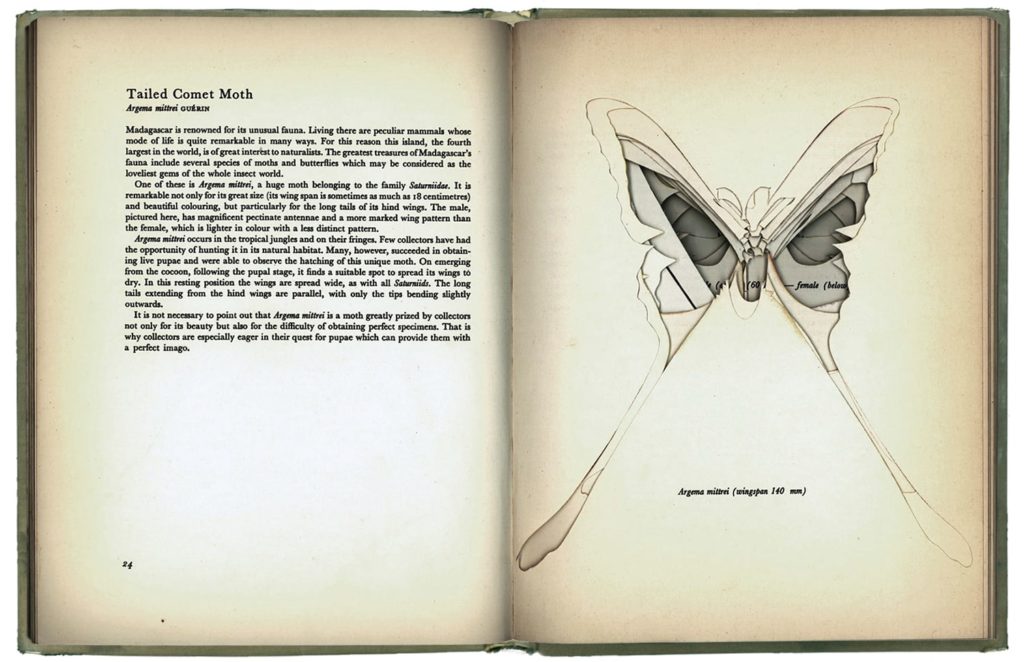

I would get books and rip them apart and keep the images that I wanted and throw the rest of the book away. My now ex-wife—when we were first married—gave me a little cutting mat. I’d always used table sized cutting mats before this. I’d bought this book which has a little moth on it, called Beautiful Moths. It was the first book that I cut up using the mat and I started cutting out each moth. I didn’t rip it apart. This book would have been just thrown away.

It was funny because when I was done cutting it out, as an afterthought it was, oh, I’ve got a moth-eaten book of moths. So it was purely fortuitous that it was the first book. So my rule is that if the imagery in a book is in the shape of an object, then I will keep the book intact and cut each out.

So again, I contend that I’ve come to view the archive as something very living. And for a long time it wasn’t, it was very static. I mean my archive is organized by subject and by publisher. But about 15 years ago, I took my hundreds of categories of envelopes that I had stuff cut out in, and it was a self-sabotage moment, but I relabeled everything poetically. An envelope full of tires became “America’s Love Affair.” I took a lot of my categories from the sides of encyclopedias—A-B and C-D. But a lot of the encyclopedias that I had had whole words attached to them, like “Metamorphic-New Jersey,” or “Peking-Probability” and so I would find subjects, and I would put them into new envelopes and relabel them as a way to trick myself into forgetting what was there. I would be reaching for the wrong thing all the time. I don’t do that anymore because it got too confusing, but for a little while it had a really great effect on these strange forces that would come in to a planned work and shift it a little bit. Which is something I’ve been wanting more and more of.

Translating Experience

AB: In one of your previous interviews you said that you want, “…my viewers to have the same experience I have when I’m a viewer.” I was curious if you could talk about what that experience is.

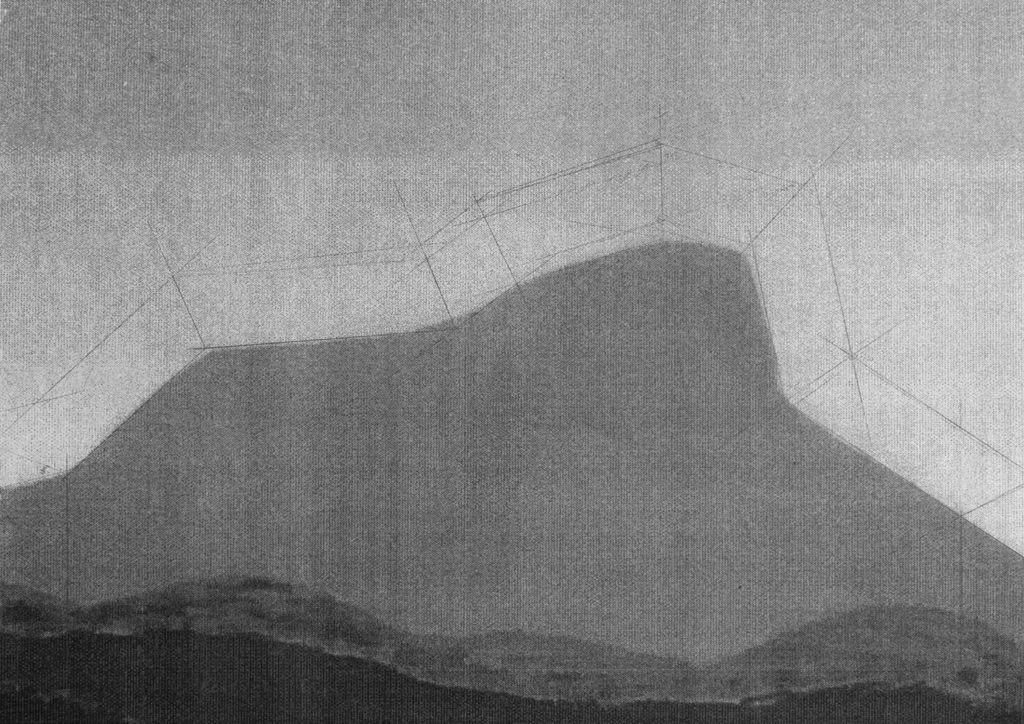

MO: I can’t offer the same exact experience that I had. But I think there are several experiences along the way that I can: there’s finding the material; there’s recognizing what I’m going to do with it through drawing, making the plan. I think if your viewer can make contact with that, and the piece survives that knowledge, and is still mysterious, that’s incredible.

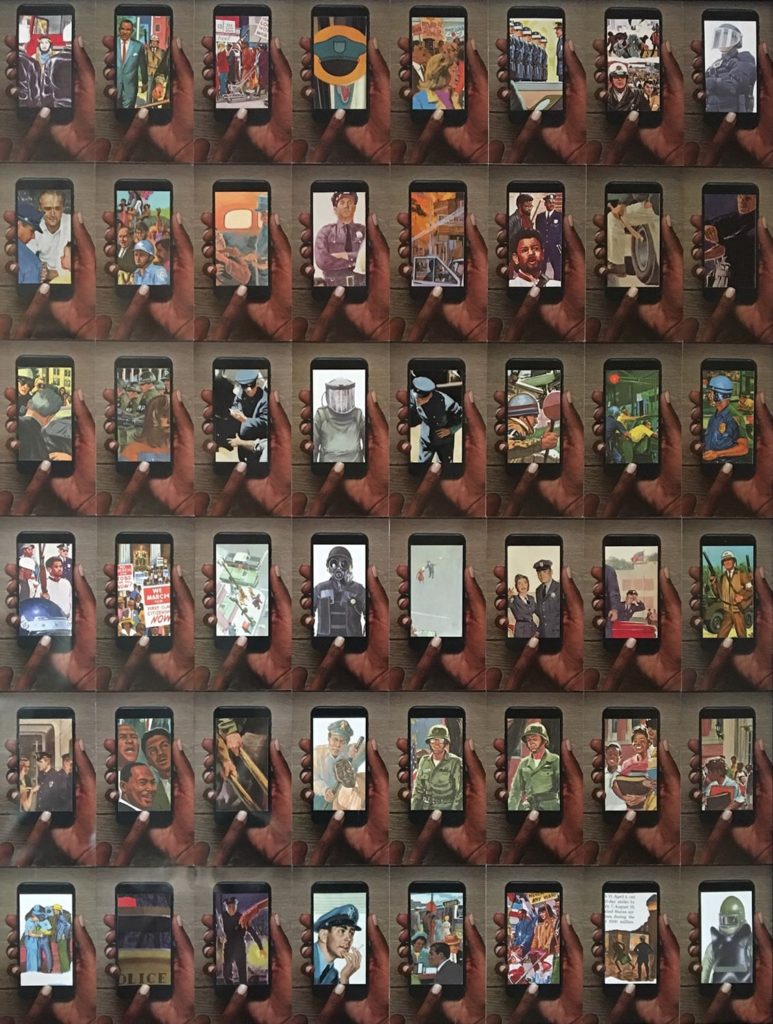

The next level of experience might be when I started to change the scale of the collages, when I went from making about 8 x 12 inch collages to making collages that were 12 feet long. Now 50 feet is the longest one. Suddenly the viewer was walking and looking, and that was simulating the camera pan from cinema. If you were looking up and down a very tall one, that was another camera movement. You saw a collage from a distance and it looked like snowflakes, and if you “dollied in” closer, you saw that they were made out of hexagonal arrangements of fighter jets.

There was a shift, a perceptual shift there that was all about the viewer’s experience. And I think there’s also this idea of how do we look at things? And how do we look deeper at things? And can you anchor your viewer, or not anchor because I like them to move around, but can you keep your viewer’s attention there for a longer period?

My First Significant Subject

I got a text recently from the director of the Bennington Museum, Jamie Franklin, sending me a link to a legislator who he had met several days earlier, who has, with a group of other Vermont legislators, just penned the first eugenics apology that the state will officially issue. I started tearing up because I had done a big eugenics project in the ‘90s which was in a sense the first real public encounter with these stories since they had happened in the ‘30s and ‘40s, and even up through the ‘60s.

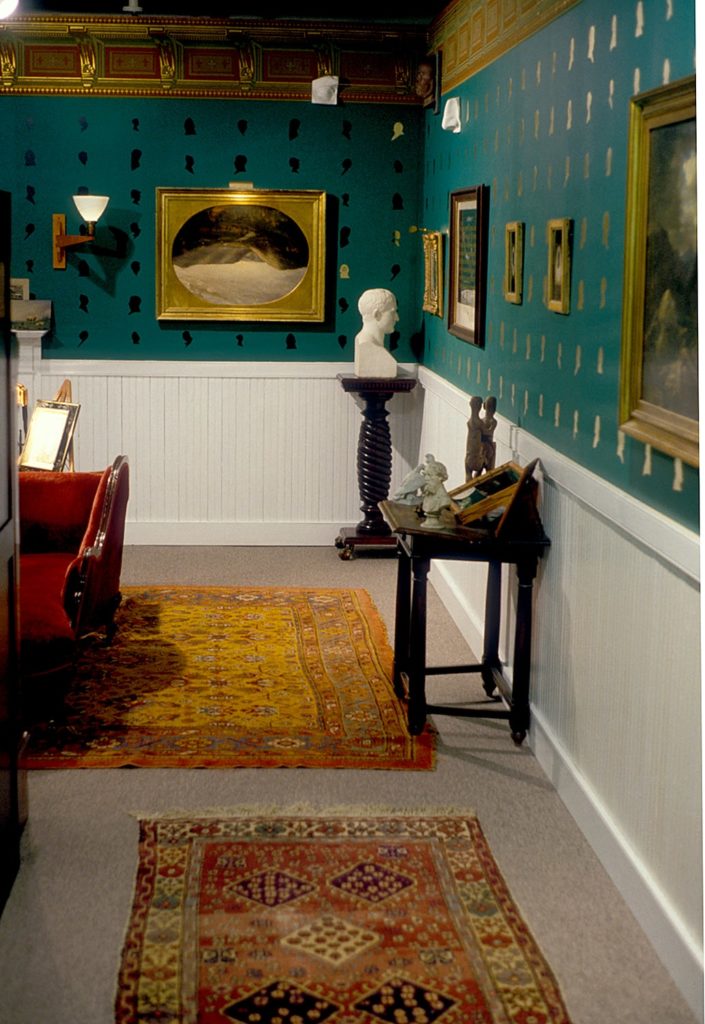

That project was using the Fleming Museum in Burlington, Vermont’s holdings as a prop room to create a very hyperbolic environment that put the viewer at the center of this really horrific history of coercion, racism, sexism, and classism. It was my first real encounter with thinking about the audience members in terms of their experience, not only in the show, but in terms of what their history might be.

I had to become a detective in order to make the show. I had to wander into physical locations, into the stories of marginalized people, into their lives and interview them. I had to ask the questions like: How do we know this really happened? How can I, for the first time, make an artwork that is grounded in real historical events, and not just kind of curiosity, let’s say, about museum culture? Because I had made some works earlier that were about critically looking at something that I loved, museum culture, and realizing that it was a colonial practice.

I was making a space that had never existed, but it was filled with some real possessions of Henry Perkins (a biologist deeply involved with eugenics), artifacts from the anthropology department and slides that were used in the Race and Heredity course at the University of Vermont. I was using history in the way that Picasso says art is “the lie that tells the truth.”

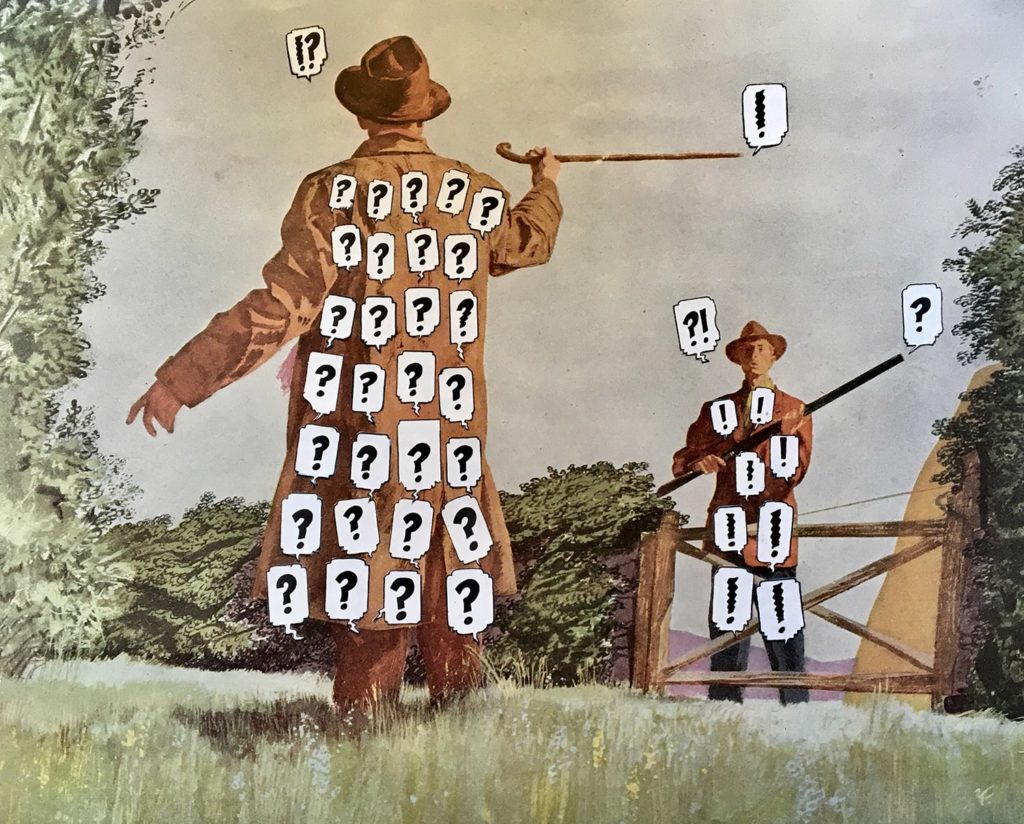

Photo Credit: Michael Oatman

And the veil was lifted from my own eyes. I got letters, and the installation got letters. People were writing to the show and saying, here’s my experience, my uncle was sterilized when he was 18 years old. I met people who had lead these lackluster lives after forced sterilization. I met scientists and geneticists.

I realized then that the viewer’s experience did not stop when they went on to the next painting in a gallery. The viewer’s experience is their collective encounter with the world. And we intercept that on occasion. There’s an opportunity there to participate in their life, to make them take stock. And sometimes it’s a two-way street when you meet or hear from your viewers.

So, whenever I can, there are invitations to the public to leave things, to respond. It’s really happened with every installation that I’ve done that’s been based on historic research.

New Directions in Narrative

In All Utopias Fell at MASS MoCA, we’ve had people leave personal possessions, record albums, decals and books. Nude photographs and Polaroids. People have been busted by security having sex in it. Somebody took a poop in the toilet, which, after that, we had to screw shut. People feel certain permissions in these installations, I think, partly because I want to make it a visceral experience. I mean talk about visceral!

The other thing that I’ve learned over the years is that I’m not really a gallery artist. I mean I love it when I have shows in galleries. But I like the audience encounter where they take over or feel certain permissions. Or even transgress, and perform acts of theft. Sometimes my images have gotten to that level of involvement or provocation, but it’s more the spaces, really. I think the truth is, I feel the same acts of transgression coming on when I find something. I mean, I know I’m going to cut up that book…

AB: Hearing you talk about people interacting with your installation reminds me of the first story you told. It’s like bringing your stamp to the post office and having that unexpected response to it is what completes it.

MO: I’ve never thought of that. I think you’ve just made me realize that Joe Keyser was my first curator. He was my 7th grade cultural shaper.

Early Influences in Material Culture, Environment and Mystery

To back up even further, my paternal grandparents in Vermont had an extraordinary house. In addition to my grandmother’s collection of hundreds of Toby Mugs on a big display shelf inset into the wall, such as you sometimes had in a Victorian home, my grandfather had 300 clocks. 100 of them were wound daily or weekly. It was a ticking environment. 200 of them were in the basement under plastic sheeting, an effect that I recreated in a show at the Tang Museum a number of years ago in a piece called Iceberg.

Going to their house was an amazing treat because it was a world of collecting. A world of sounds, of a very special and secretive guy. My grandfather performed magic tricks. He would slip us silver dollars when we were leaving. He was the accountant for the fire department, but he was also a fireman, so we’d get badges sometimes.

It was material culture writ large and very embellished in a house with roll top desks, regulator clocks, clocks under domes, a 10 foot tall grandfather clock, an incredibly steep Hitchcockian staircase and a basement filled with mysterious tools, because a lot of them were for fixing clocks.

They were my dad’s parents, so I tried to figure out what he had inherited from them. And there was never really a serious collecting gene in my dad, but he had inherited his grandfather’s and his great-grandfather’s tools. He was an avid fly fisherman and had lots of gear for tying his own flies. He could make anything, which seemed to be another trait of his father’s. So that, combined with Joe Keyser’s influence, was really all about collecting, display, finding and organizing.

All of them were true collectors. They weren’t makers in the sense of doing something with all that material, and that became my role. It was something that I drafted my parents into complicity with me. I had them make things for my installations. I think in the last 20 years of my practice, there probably wasn’t an installation where there wasn’t a thing by Gordon Oatman or Shirley Oatman that was made at my direction.

The Goal of Collaboration

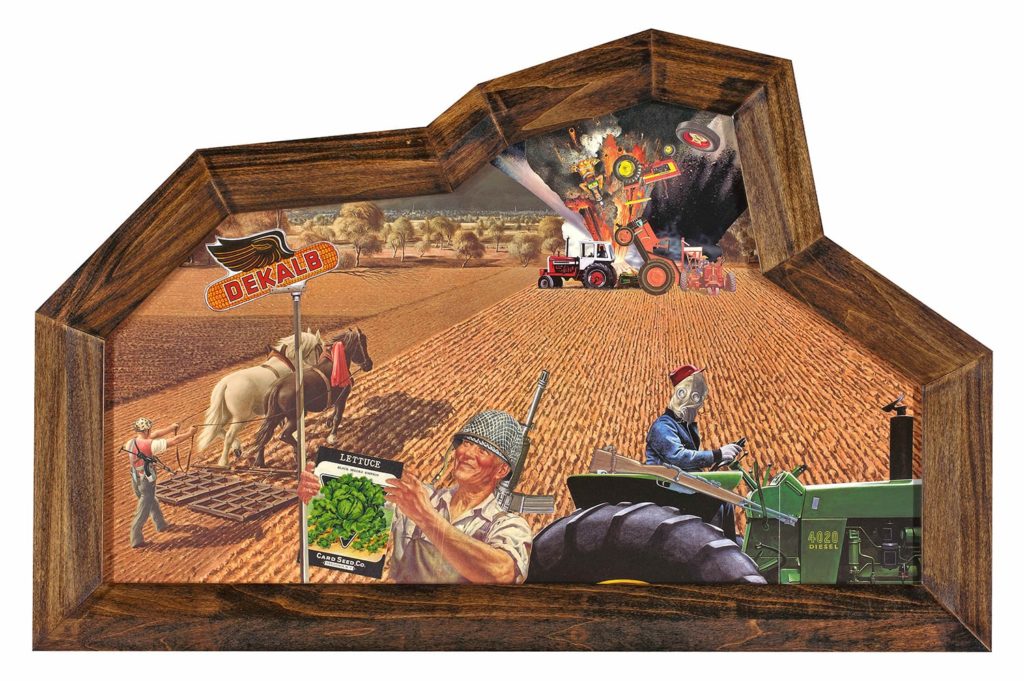

And then, finally, in 2012, my Dad asked me if I was coming home for Thanksgiving and said, I’ve got an idea I want to run by you. So I drove up to Burlington for Thanksgiving, went to my dad’s basement shop and he shows me a drawing of a Native American thunderbird shape—big, with long wings. And he said, “I’m gonna make these shaped frames and I want you to fill them.” And that moment was something I’d been waiting for 25 years.

I always went to my parents with the proposal for a project: I need this stuffed animal; I need a flag in the shape of TV color bars; I need you to make me a pillory for 12 sock monkeys. So my dad made the pillory, my mom made the sock monkeys. But this was my dad proposing a project to me.

I was so delighted. He made this shaped frame and it took me a year or more to figure out what to put in it. I eventually made a piece called Germinal Velocity and the subtitle was By the Time I Get to Phoenix She’ll be Rising, a Glenn Campbell song. But “germinal velocity” was a term that I thought I had invented. It turns out it’s a real term, it’s the amount of time it takes life to happen somewhere. Maybe another planet, which is what I was thinking of.

So I made an image of the surface of Mars, the Mariner spacecraft landing on Mars with a peacock on it, and its tail was hundreds of circular images fanning our infinitely. My dad made probably 30 more shaped frames for me and I’ve gotten through about half of them.

Inheritance

We had a show together in 2016 called Oatman and Father, Signmakers. One half of the gallery was his big xeroxed drawings for the frames so that he could get the proportions. And then several of his unvarnished frames in the shape of a shark that was hanging from a rope in the ceiling, to a butterfly. I had filled frames on the other side, frames that he had made with my imagery inside. It was the raw plans, drawings and geometries of the forms, and then the forms themselves, and then the filled forms.

I’ve always said that I think one of the biggest influences on my collage, my installations and my art making in general is a brand of Yankee stinginess. I don’t like to throw things away. I don’t like new things as much as I like things that have a life and history. So that was one of the reasons I went away from being a pure painter. It was too interesting to find these things that had a private life and to respond somehow.

My dad was a big re-user, a big re-purposer and a fixer. I’m not as much a fixer, because I’m not as technically minded. But my biggest interest has been in salvage and repurposing. I think that I have a somewhat sustainable practice. I have a lot of stuff, don’t get me wrong. I have a community center that I’ve filled with stuff. My friends think I’m a hoarder, my girlfriend thinks I’m a hoarder for sure, but I like to clarify that I’m a very organized hoarder. I use the stuff, I don’t just keep it, I eventually get to it. As I said, one of my chief tools is — well, it’s not fair to call it forgetting—it’s the re-encounter. You buy something, you put it away. Or you cut a bunch of these out and you file them.

I’ve certainly gotten very interested, in recent years, in the arc of artists’ work. I’ve had a few curators who want to see everything, and it’s a 2 or 3 day operation. It’s a startling encounter because, a lot of the things I don’t remember making at this point, and I’m not sure why. I mean I recognize everything, certainly. But its other lifetimes.

Remembering the Future

Every once in a while, I’ll encounter an object that I made, like a little sculpture, and I sort of wonder, why didn’t I pursue that? That was really interesting.

So in some ways it’s the echo of that Max Ernst syndrome—doing a lot of different things—and nothing really quite hitting for me to do for a sustained period, except, I will have to say, my collages. Even though they were small at the beginning, it’s something I’ve always done, regardless of making installations or videos or paintings. I’ve always made collages, which, as they get larger and more complex, are infinitely challenging and satisfying.

(Coming soon, part 2 of the interview)

Photo credit: Michael Oatman