This is the third part of Todd Bartel’s Interviews D. Dominick Lombardi. If you have missed the other ones, start reading here.

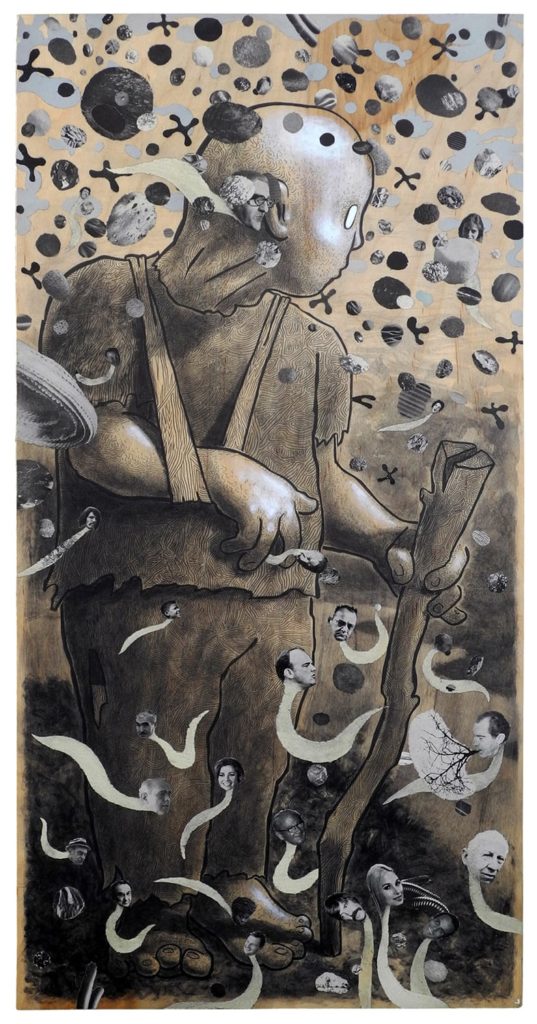

TB: While absurd mashup runs rampant in your work, or what you like to call “cross-contamination,” I think there is another rather beautiful and hopeful aspect that connects all your work. You often mention that you adopted your grandfather’s “obsession” with repurposing raw materials like salvaged wood and hardware, which is evident in everything you make. Son and grandson of carpenters, you began learning how to use wood-working tools as early as 12. You were also influenced by their modeling the recycling of materials with a proud and robust sense for craftsmanship.

I wonder about your dedication to craft and the processes you employ that require focus, dedication, and meditation. I wonder if this aspect of your work is something you concentrate upon, want to communicate visually to some extent, but do not necessarily speak about verbally. I ask because as I look at the threads that connect one project and series to the next, something seems to run deep throughout all your art. I would describe your work as privately spiritual. I realize that today’s American culture — particularly the art world — does not embrace the topic of “spirituality” readily, if rarely. For many people, this aspect of our humanity is too closely associated with specific religions. Given our pluralistic society, there is a tendency not to discuss “universalities” because of an abundance of distinct and differing beliefs that do not necessarily dovetail. By “spiritual,” I mean that holistic aspect of the human persona—your persona—that is an amalgam of your emotional and intellectual interior life in tandem with the exterior world, your various communities, and how you choose to live and interact with all things and beings. I perceive a deep caring and humanity within your work—a resonant and connective spirit. Could you elaborate upon what I perceive to be an intended spiritual invitation to viewers? How does your work contribute to the human condition?

DDL: I agree that the term spiritual can be problematic. But I also agree it applies to my work. I often use the term spiritual when I write about other artists because it speaks of a higher plane, not in any religious context, but in the collective unconscious as termed by Carl Jung. There’s something out there that we can’t easily explain, except to say it’s a feeling we are connected in some way to the past and the future as the concept of time is a human construct. There’s also the spirit of the land, as with the work of Charles Burchfield, where there is that higher plane expressed between the land and something beyond — perhaps in another dimension.

Great art, to me, has to have passion, and that passion definitely includes one’s spirit, one’s soul — the psyche. I see that same spirit in your work Todd; it’s there because of what you put in about yourself, your life, your important, enlightening moments. That connection to a place, to others, people we knew well — like my father and grandfather — and how they live in us, through us, and in our art. That is best described, I believe, as a spiritual connection. Regarding the process and craft, I come from a blue-collar background. I was exposed to carpenters, plumbers, electricians, masons, HVAC specialists, etc., who were from a generation that saw what they did as defining who they were, as they took the quality, that built-to-last concept very seriously. They knew nothing of planned obsolescence.

Also, the process of fabricating; the satisfaction of creating something you could only previously imagine lifts one’s spirits. And seeing and experiencing great art in all its forms feeds the spirit. I remember when I saw the works of Titian, Tiepolo, Tintoretto en masse in Venice back in 1980. I started tearing up — it was overwhelming. What is that if not a spiritual experience.

As far as the human condition goes, I’d like to think I am bringing important issues that relate to everyone and that those connections can help initiate the beginning of or thoughts about change for the better. The world is in flux now more than ever. Sometimes we need to step back and look at what is happening around us and think about how we can help make positive change. We all do it in our own way — whatever is comfortable for you. For me, it is everything from pointing to the effects of pollutants on humans and animals, to the injustices of the economy, and how that sets many up for failure or oppression, or something as simple as common anxieties many of us have — that all comes from my interest in studying people, society, how that all works at any given time in a variety of circumstances.

TB: That’s very affirming and very inviting Dominick. Agreed, I think we all would benefit from openly discussing the spiritual part of creation. Now more than ever, we need to value what is collectively sustainable.

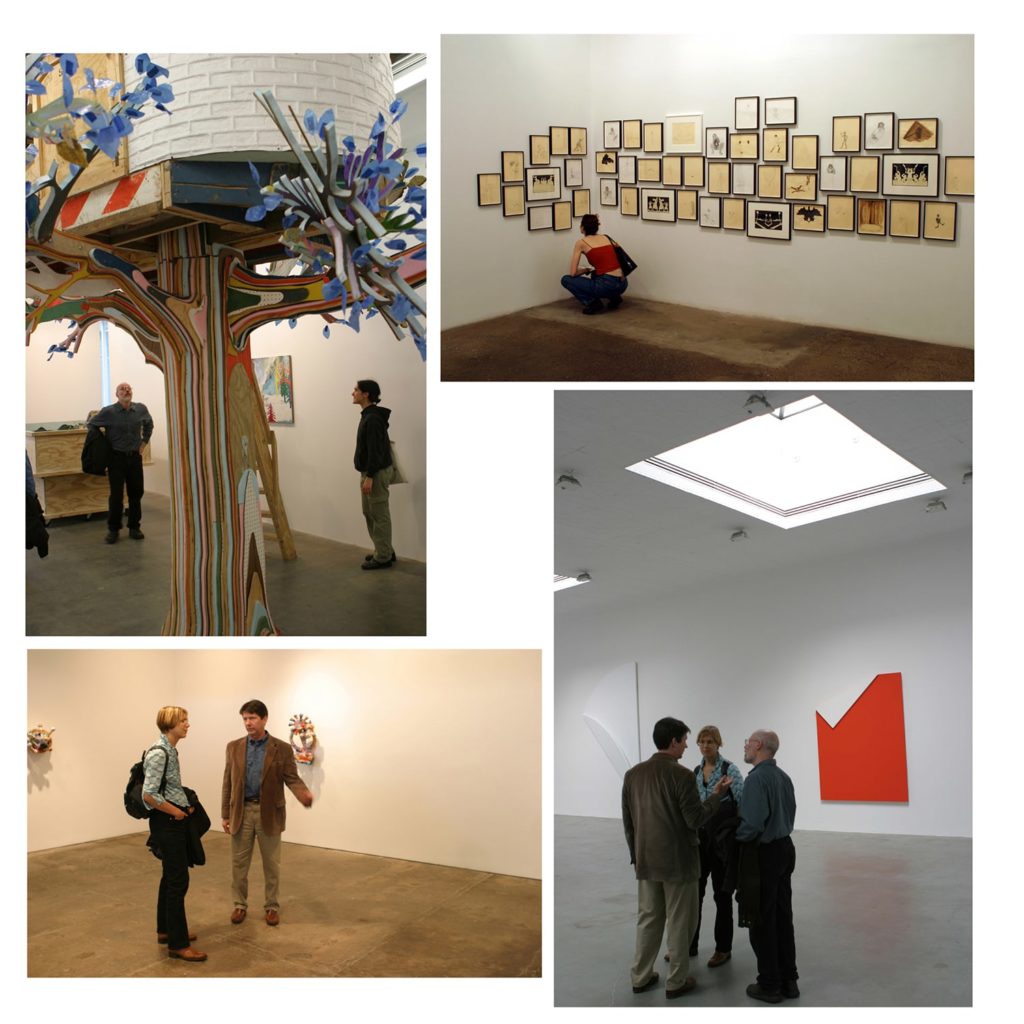

As an artist, curator, writer, you have had a unique set of opportunities that gave you insight into the often separate, sometimes divisive, nature of the art world; somehow, you found ways to dissolve some barriers. For example, in your “Art Safaris” and curatorial work at Art Lab, you tried to “normalize” and “make more comfortable and human” the relationship between looking at art and discussing it between constituent groups that generally don’t meet every day. You provided tours of galleries in your Art Safaris and Art Lab exhibitions. You organized dinners—as opposed to openings—in which individuals within segregated sectors of culture could “break bread together, and discuss the art world.” As you point out in your documentary [Visual Voices: D. Dominick Lombardi — Resilience and Focus] in NYC and “especially in SoHo, there was a coldness and a barrier between the general public and the controlling art world. To me, it was important to break that down as much as possible, by having people sitting—artists, curators, collectors, gallerists—and just have fun together, and drink together, and eat together, and spend time together.” What strikes me as unusual and important is that you had so many hats you found yourself in new territory where the boundaries between vocations also, at times, needed to be defined. In the same documentary you asserted:

“Everybody wants you to write about them. Some people want you to curate shows for them. But very few people need artists, there are so many, and it is so competitive that you really have to be careful and make sure that when people introduce you and they say, this is Dominick, he’s a writer from blah, blah, blah, at some point in the conversation, you need to make it clear that you are an artist and that this writing career and your curatorial career is really just a part of your artistic endeavors. It’s part of your approach to art. It’s part of your message that you do not separate them, that they are all one and that you are at your core, an artist first.”

What was is like to blur the distinctions between vocations, while also having to maintain autonomy between them? And, could you share an anecdote or two to provide our readers with specific examples of how you dissolved art world divisiveness?

DDL: The Lab gallery was a unique place and time. I was brought in as the Curatorial Advisor by the Roger Smith Hotel’s James Knowles, whose family owned the hotel and the space on the corner of 47th and Lexington Avenue. Matt Semler and I presented about 25 exhibitions per year, as I was responsible for curating a few shows and bringing in outside curators to offer their exhibitions. I remember quite clearly, sitting in that street level space, which was very much like a fish tank as it had glass on two sides, having banquet tables set up and dining with artists, art writers, curators, etc., all the professions you mention in your question, and just having fun passing the night away. I’m not sure what transpired or what was transacted with all attendees, but for me, it was magic — to make the art world more human and intimate.

And there were also many variations on the theme. At one dinner, in particular, the artist Trong Gia Nguyen, who was based in Brooklyn at the time, had us all eating on a table that was actually a stretched canvas inside his installation titled shäp. The resulting dinner stains and markings of that first night’s party were part of the exhibition from then on — a brilliant idea in the context of an exhibition. There was also another time that Rodney Dickson recreated a Queen Bee Snake Bar and Tea Room, a type characteristic of Viet Nam, where “US Soldiers went, to look for Vietnamese women”.

During Rodney’s installation, we had issues serving liquor, so everything was just given away. You can imagine the scene in midtown Manhattan, the happening spilling out into the streets in an area where you would normally not see such an event.

This was all a part of the general focus I have when it comes to such events, efforts, or activities. I see it all as of one mind, the transition between my work in the studio, the exhibitions I curate or am involved with, or the shows I review. I do it all because I enjoy it. It gives me a different vantage point or perspective on the art world. It feeds my spirit; it feels right.

The Art Safaris I organized in New York City were the same basic idea as the Lab gallery, as it brought individuals from all walks of the art world together to experience art in a variety of galleries in a particular district in NYC, discuss what we were seeing as we go, and perhaps even staying for dinner afterward at a nearby restaurant to discuss the standouts of the day. Having so many opinions from various art world participants can be very enlightening.

TB: I always point out that ever since the Big Bang, it’s all collage. For me, it is pointless to quibble about whether or not something is collage—because it is. Given that it’s ALL collage then, a great question to ask is, What are you doing with the things you use? That is where I think your work takes on profundity and humility. You seem to do everything in your power to make this a better world. Would we be correct to urgently glean the following invitation from your work: PEOPLE CAN WE COLLECTIVELY GET IT TOGETHER?

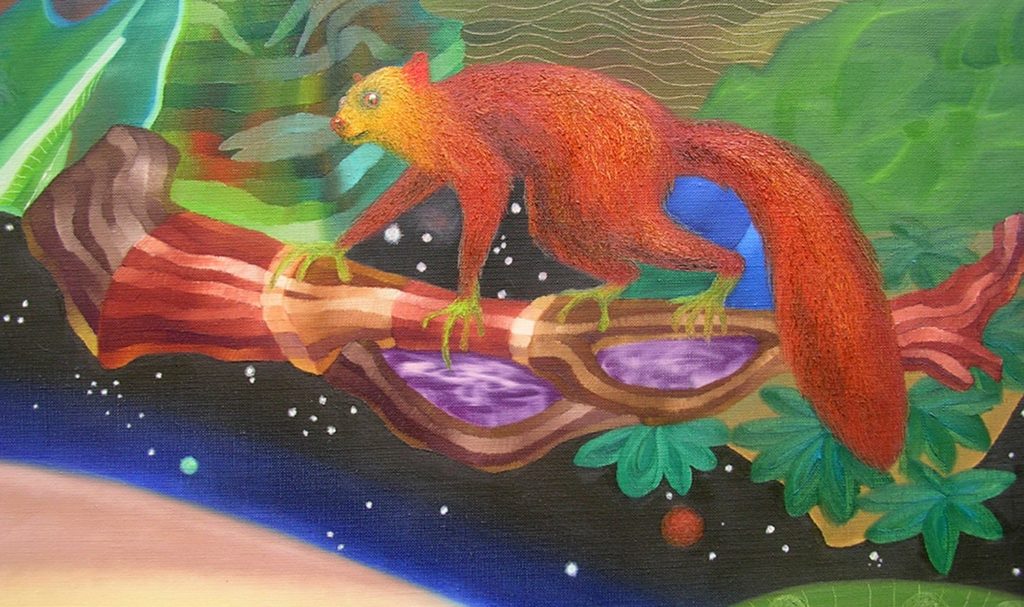

DDL: I love that point you make about the Big Bang, it’s such a vivid illustration of collage and that natural approach to building something visual. Regarding getting it together; from the Cyborg series in the mid-’70s, and most definitely from the Mixing Isms series in the late ’70s, I was hoping to shed light on our planet’s problems, trying my best to be the canary in the coal mine. Take, for instance, the painting Lemurs in Space(1978). That painting was specifically about the plight of Lemurs in Madagascar, their only natural habitat on earth. They are very picky eaters, and as their habitat decreased year after year, they would eventually have no place to live other than zoos or other substitute habitats — a terrible thought for me at that time, and still is. The painting I made had a few lemurs traveling through our solar system in the hopes of finding a new home planet to live in peace. Fast forward to today, and I am more focused on the hopes of immigrants and the systemic psychological effects of Covid.

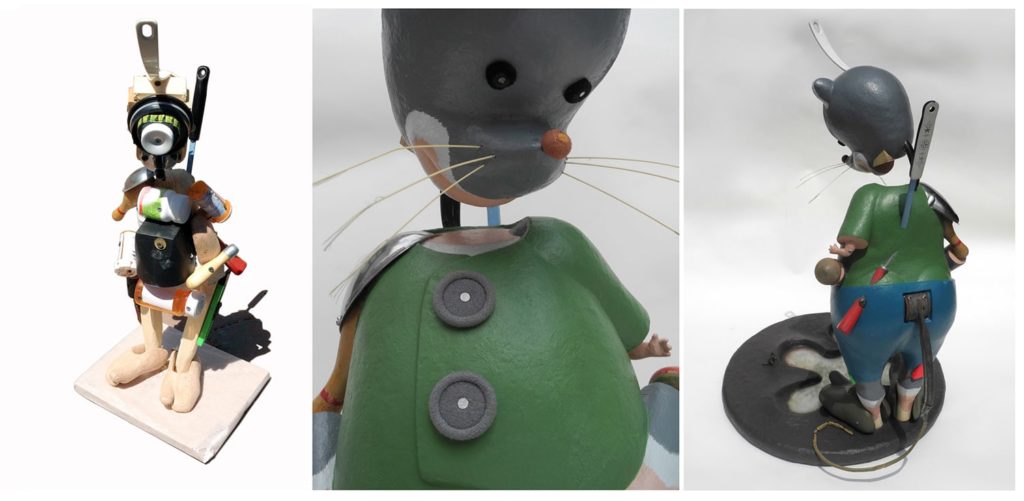

TB: Your series work sometimes transitions or morphs into a new line of inquiry. Comprised of both collages and assemblage sculptures, can you describe why your Street Urchin series takes both flat and three-dimensional forms? What pulled you to transform disposable materials, and what inspired you to evolve a strategy to reuse, recycle and repurpose post-consumer waste?

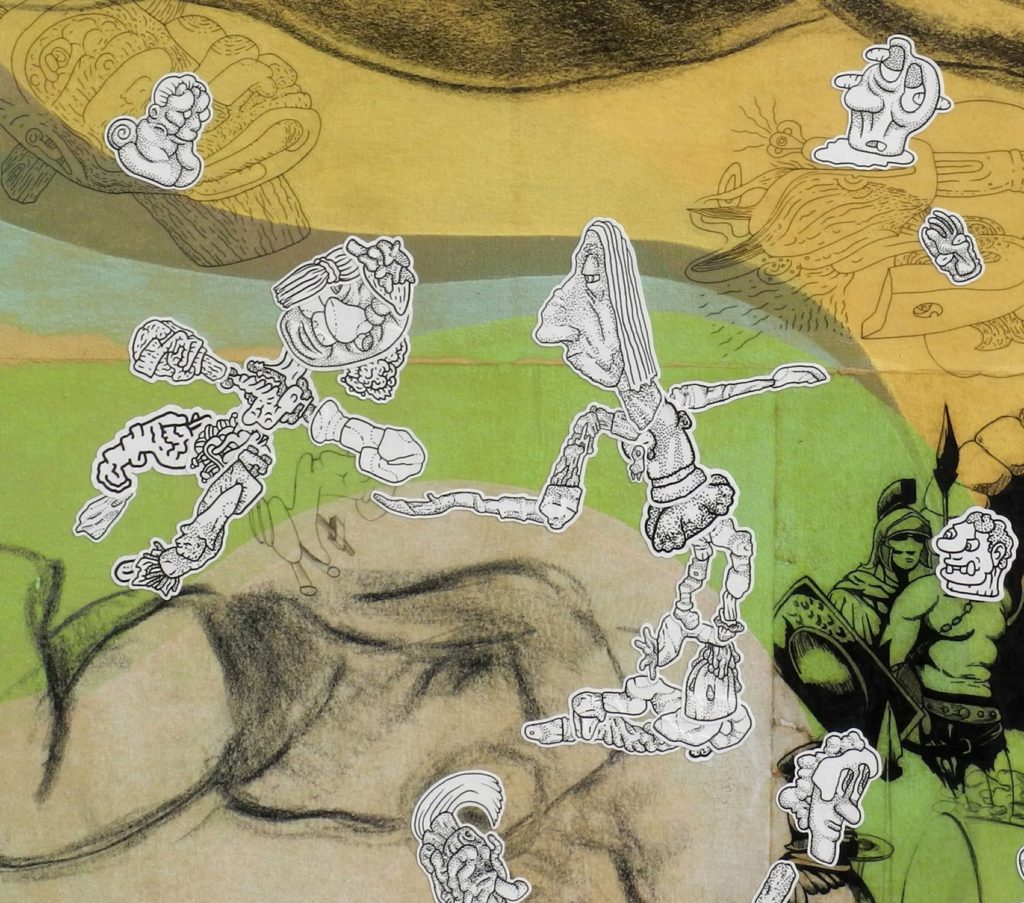

DDL: The Street Urchins were very much about the downturn in the economy in the late 2000’s. The people and house pets that were marginalized, lost in limbo as a result, became a primary focus. The sand based sculptures that were built upon an armature of discarded objects were meant to suggest that those people, those animals needed to be saved, supported, made whole again. The two dimensional works were done to place the Street Urchins in their environment, to show what they were up against, what they were seeing and experiencing. In those instances, I used vintage Newsweek magazines for the collage elements, to go with the graphite and gesso drawings.

Regarding the repurposing of consumer waste: that began a while back. When I was recovering from the 1986 car accident, I began carving to build up my hand and arm strength. I began with pieces of cedar shakes that were being discarded from a home construction site, which ended up being used in the painting Witness Against Logic (1987). From there it just took off, repurposing anything that could be re-used, reshaped or painted in my sculptures and paintings, including what I had previously made and put aside. When there was a downturn in the economy in 2008, the repurposed materials took on new meaning, multiple meanings, including the value of preexisting materials, which inevitably came to represent the merit of the marginalized. Repurposing also fit perfectly into the essence of collage, and as you yourself prefer, I gravitate to older materials such as vintage magazines, books and newspapers. The fact that I am repurposing materials hints at how history repeats, and that we will eventually come out of our troubles. We just have to use more ingenuity and creativity for the time being until the next time when we repeat our mistakes.

TB: As you know, I’ve been asked to curate a collage-based exhibition in Duxbury, Massachusetts in honor of The Art Complex Museum’s 50th Anniversary in the spring of 2022. For this show, which I titled Complex Muses, I invited you and nine other artists to respond to a work from the museum’s collection that will be on view for the first time. You have described being influenced by other artists as a referential strategy of the collage aesthetic, but for Complex Muses you chose two works to respond to for your contribution. Have you ever done that before? Given that you look for ways to blend and juxtapose materials and images, can you describe your inspiration for this project?

DDL: I have done homage paintings before but never a sculpture that celebrates a particular artist, and I have definitely have never combined two homage to create one. The two works that I selected to celebrate in my sculpture are 17th century Japanese Netsuke carvings, little sculptures that adorned men’s kimono sashes where they stored personal belongings. One Netsuke is of an artisan, who I assume is carving an object in accordance with the prompts of a mythical creature. The other is a toad or frog that symbolizes loved one’s safe return from travel. My plan is to repurpose found or discarded wood, carving a portion to create a figure that incorporates my impression of the two Netsuke objects, combined with my familiarity of Japanese art and culture based on my two visits there in 2008 and 2017. Specifically, my guess is the Mythical creature in one Netsuke carving is advising him on the details of a ceremonial mask, which I plan to use as the head of my assembled subject, as the basis for my content.

High+Low, A Forty-Five Year Retrospective, which first appeared at the Clara M. Eagle Gallery at Murray State University, Murray, Kentucky, is currently on view at Marie Walsh Sharpe Gallery of Contemporary Art at the Ent Center for the Arts, UCCS, in Colorado Springs through December 12.