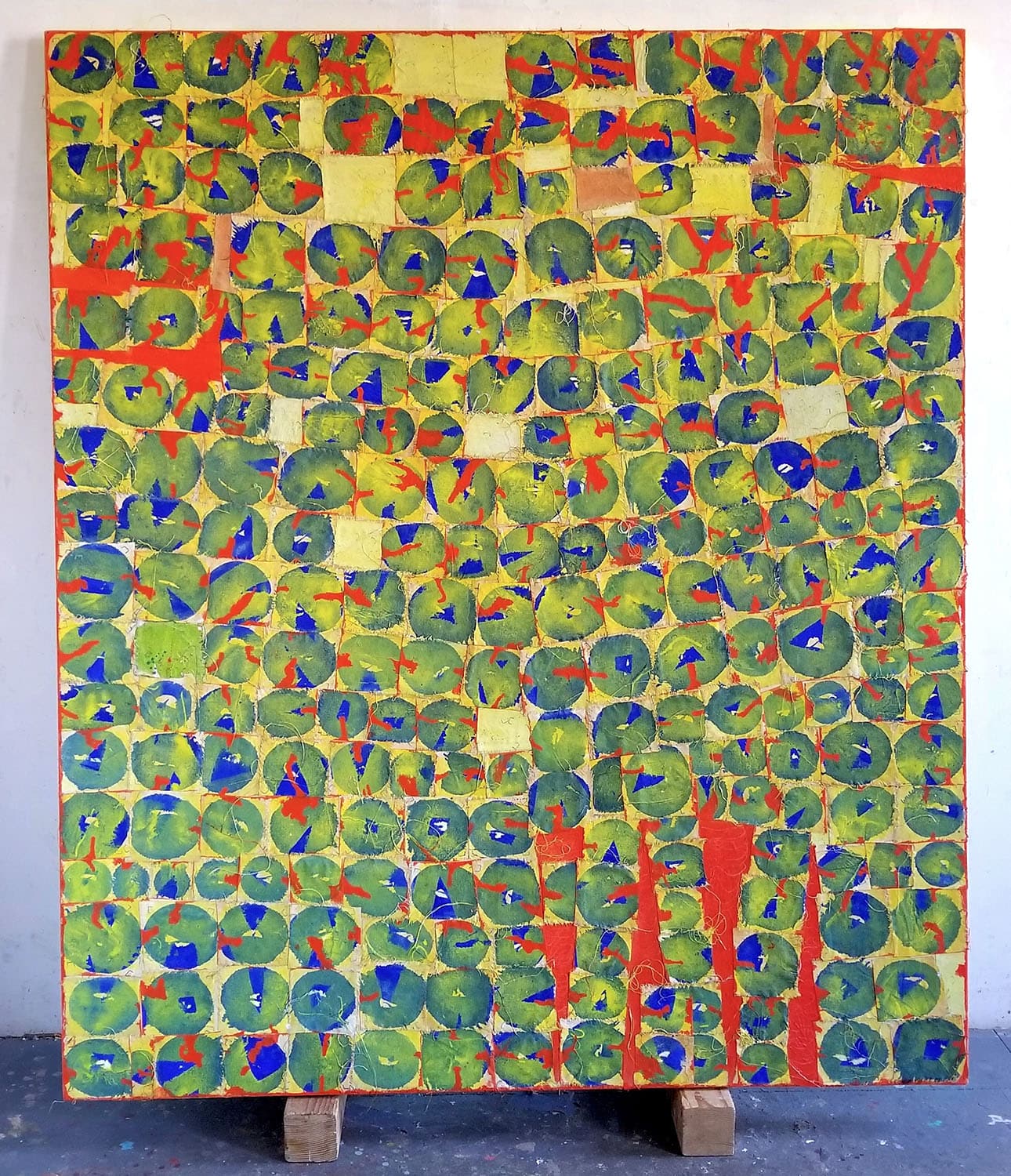

Palpitating with color and rhythm, there is an energy to Douglas Florian’s large-scale painted collages that makes them seem to have effortlessly jumped into being. Upon close examination these works are complex weavings of not just formal elements, but layers of language and symbols. We visited Douglas’ studio in Hell’s Kitchen, NYC to learn more about his work and many sources of inspiration.

AB: From your large-scale painterly works on canvas, to the many children’s books that you have written and illustrated, collage seems to be a through line in all of your work. Why were you first drawn to collage? What has made collage such a significant way of working for you?

DF: I actually think it’s genetic, like a predisposition to insomnia or laziness. Even as a young child I loved making collages. I’m drawn to collage because it makes revising art easier. You cover up your mistakes instead of scraping or painting them out. And collage at its best is great for connecting disparate elements together into a cohesive whole.

AB: The rhythm and colors in your work evoke a sense of musicality, I believe you described the colors of your work as music. Can you share more about your relationship to music? Do you listen to music while you work? Or does your work, in its way, create its own music?

DF: I think my work is connected to music because it’s very rhythmic and full of vibrant color. Sometimes the reference is overt in a painting such as Samba Bamba Cool Green Mamba and sometimes covert in a work such as My Lovely Green Avalanche. Music moves through time and I want a sense of movement in my work.

AB: Looking at a work such a Zeno’s Arrows, with disassembled words spread throughout, I think of chanting and incantations, these situations that separate words from context, yet emphasize the power of the word itself. I wonder how you think about language and its power.

DF: In a painting such as Zeno’s Arrows the words are disassembled so that they are not obvious but rather discovered by the viewer as they scan the work. This is why the paintings need to be seen from afar, where the entire composition is clear, and up close where texture and materiality come to the fore. I want the letters to be very organic, almost like animal or plant forms, rather than strictly typographic. I want the letters to tilt and nudge and drip and drop, like living things.

AB: The titles of your work seem to serve many functions, sometimes adding additional layers of meaning (such as Einstein’s Compass), evoking a particular way of looking at a piece (and the sea the sea crimson sometimes like fire), or provide an almost musical accompaniment (Samba Bamba Cool Green Mamba or Harmonious Erroneous Felonious Thelonious). Can you talk about the different relationships these pieces have to their titles? I am particularly curious about the story behind The Night the Cat Stole My Dream.

DF: The titles are doors to the experience of viewing the art, but I want a title that evokes rather than describes. I try to keep the painting open and subjective not fixed and static. In The Night the Cat Stole My Dream the feeing I had as the painting progressed was one of mystery and perhaps something negative, as all those x’s seemed to reference unknown variables such as you see in mathematics, and also a negation. Also, I had been reading Haruki Murakami short stories, so a cat snuck into the piece and stole my dream.

AB: Mapping, grids, and structures seem to organize and hold the elements of your work together, while other forces interact, changing directions or sometimes pulling them apart. Can you describe your approach to ideas of structure and order vs. chaos within your studio practice?

DF: The structure of the paintings is often a grid, but a grid that is collapsing or cratering inward. That seems to be what is happening in the world today. We built up all these systems to insure stability and order but through greed, ignorance or progress these social, political, and ecological structures are collapsing at an alarming rate. And this lends movement to the works, which is fine by me.

AB: While many artists use found or sourced materials in collage-based works, you make the majority of your own materials for each piece. How did you come to this particular way of working?

DF: Collage for me is in part a solution to the problem of revising a painting. If you have, say, a dark green area that you wish to be bright blue you would first have to paint a white atop the green to achieve a brilliance of color. Then you have to wait days for the white to completely dry before to paint over it. In collage you can make almost instantaneous changes, and you can first tack pieces up to see if they work. Also, when you work large, then small sourced materials, such as printed matter in books or magazines, become more problematic, unless you’re willing to tear up billboards as some artists have done. I do sometimes sneak some found matter into a piece.

AB: Can you walk us through the process of creating one of your works, from creating the initial painting, which becomes your raw material, to composing, arranging, and finalizing a piece?

DF: Each painting is different to some degree as I don’t wish to work from formula. I sometimes start from a combination of colors and shapes and then lay down a structure with a few shapes glued to the surface, often establishing a grid, and movement within and against that grid. Each piece, either a square or a strip is painted before it is glued down but I do make revisions after all or some of the pieces are glued. Sometimes a radical change occurs if the painting dictates that and some of the most successful works were dismal failures at first. It’s always difficult to know when to stop and I want to avoid overworking a piece where it just becomes busy rather than complex. In fact, usually towards the end I’m simplifying the composition until it’s most compelling.

AB: There is an effortless feel to your work, as if each one just jumped into being, though I understand that this is the result of a very deliberate process. How do you make changes throughout the process? What guides these changes?

DF: I do want the painting to look effortless and natural but it may take a lot of painstaking revisions beforehand. Often when I photograph a work and see it on my Mac I go back to it to make revisions. The work is both intuitive and counterintuitive.

AB: Looking at your work up close, it is clear how much attention is paid to every detail — how the edges of the cut squares come together, sometimes like the pieces of a puzzle, sometimes slightly overlapping; how the colors are slightly adjusted to create the perfect effect; the decision to leave in the imprint of staples in the paint. Are there any other details or overlooked parts of your process or aspects of your work that you would like to share?

DF: Because I may work with cut squares, the result can resemble a mosaic when the edges abut each other, rather than overlap. Working with linen, I love how the threads may come loose and sit on the surface or how the colors may bleed through each other, run down, or pool up. I prefer the irregularities of linen to aid this in ways that cotton cannot. I also like how older pieces beneath peek out in spots. I sometimes use lines of colored pencil on top of a color to enrich or enliven it and get away from flat color. I do sometimes sneak staples, or lines made with a cookie cutter, or eyes into a piece, all seen up close.