An Interview by Andrea Burgay

All photos furnished by the artist unless otherwise noted.

AB –A residency at Weir Farm seems to be perfectly in line with your work. How has your time in this particular space influenced your work?

TB –Even though I had very specific things I wanted to accomplish while at Weir Farm, I also wanted to take advantage of the history of the location, which is not insignificant in the history of landscape painting. Julian Alden Weir (1852-1919) is one of the founders of American Impressionism, and I took advantage of my proximity to the birthplace of the historical movement and dedicated my mornings to research. The park has a small but wonderful library, and I borrowed several books which filled my imagination and initiated projects which I am actively collecting text and imagery for; I plan to add a work or two about Weir’s contributions as well as the birth of the American suburb to the LV series.

Every day I read for the first two hours of the morning and earmarked dozens of passages that are of interest. The other thing that was more subtly influential was looking at and studying Weir’s paintings and how that informed my eye as a creator. While it is understandable that the cottage where I slept does not have his original paintings, the facsimiles are quite good and there are several original paintings at the Weir Farm Museum and Gallery, which I spent a lot of time looking at and studying. I also took advantage of the trails, took in the surroundings regularly, and amassed a lot of photography that may prove to be a storehouse of resources in my studio practice in the future.

Weir was a realist who used color truthfully but also emotionally—I found his paintings to be singular, iconic, and haunting. Specifically, I appreciate Weir’s strategy of placing obstructions in the path of the viewer as well as cropping the view of a given scene in unexpected ways. This was a topic of discussion for the museum curator, Jessica Kuhnen, who provided a lot of insight and further reading, not to mention provided access to the museum’s digital archives and highlighted passages in letters Weir had written. I still have access to the museum’s archives and consult them from time to time.

What was most surprising was noticing the way I frame a photograph changed while at Weir Farm. Imagine that, after decades of photographic experience and thousands of photographs taken, I changed the way I take images due to Weir’s influence! I found myself moving my camera off of central alignment to my body to obtain oblique views with obstructing objects between me and the thing seen. I began experimenting with taking photographs in an obstructed way. I also got permission to temporarily remove Weir’s facsimile paintings from the cottage and take them with me along my walks to photograph them in situ. I produced a small series of eight Painting Exports.

Finally, perhaps my biggest takeaway from J. Alden Weir is that I want to research and write an article on Weir’s practice of “Holly hocking” — embellishing a painted scene by adding pops of color (extra flowers) for the sake of the image. In light of his attitude toward naturalism and truthful observation to capture the moment, I liken Weir’s attitude toward such embellishment akin to a collage practice. Given my thesis, the history of collage and the history of landscape painting are the same story, I am greatly interested in how Weir reached for more of a thing, in order to capture the spirit of the place at the expense of his attitude to be true to shat he sees.

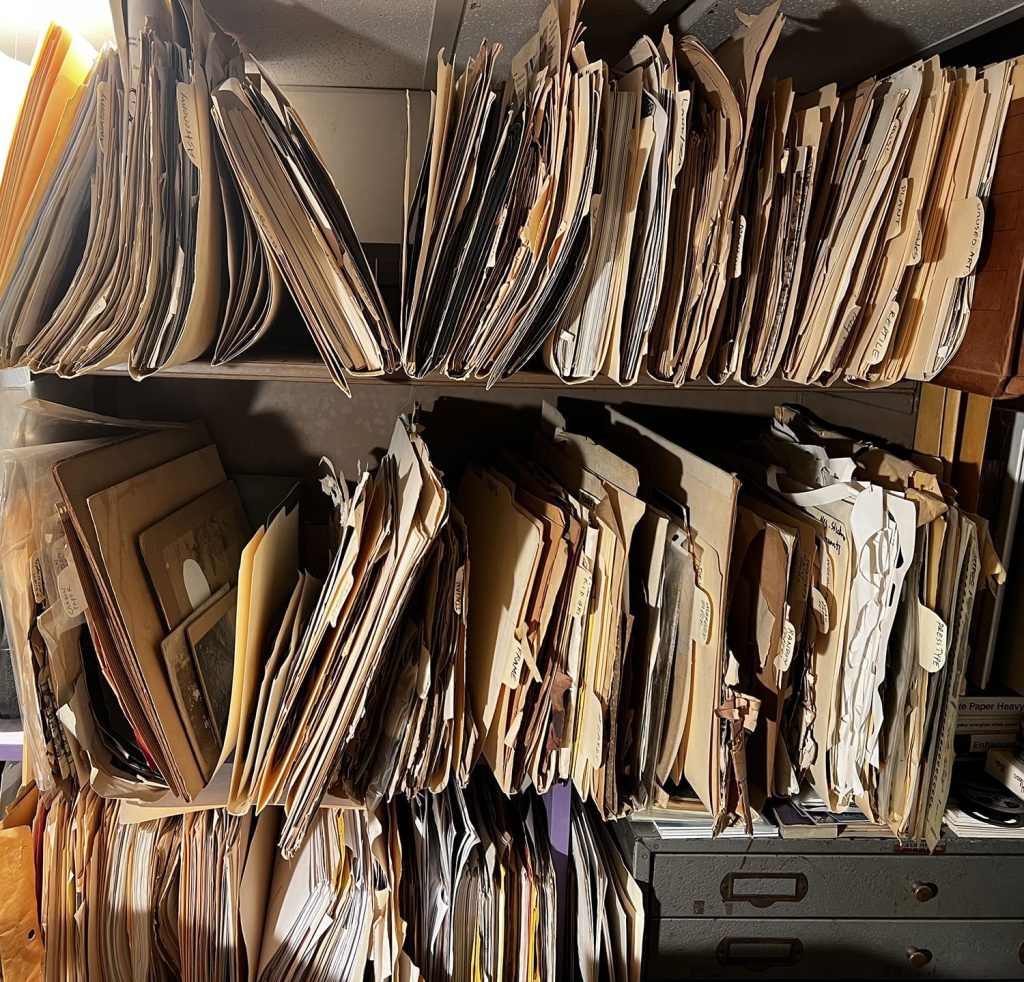

AB –In your studio space, folders collect materials for upcoming projects, and stacks of books and documents form research libraries related to the topics of your work. How do you organize the many aspects of each idea and project? How does the deep research of each project become visible to the viewer? And how did you decide what materials to bring to this residency?

TB –Thank you for this question! The short answer is that the individual collaged texts and images act like stepping stones that require a mental leap from one to the next. How I select the material to import requires commitment to research and collection.

While in many ways, I must honor and credit Joseph Cornel for his use of the “dossier,” creating receptacles for collected magerials is a basic materials for any collage artist. I have been storing my materials in folders ever since I first started making collages seriously in 1983. First of all, it was practical to bring materials to and from my home studio to the classroom during my junior year at RISD. But what really forced the practice was purchasing an entire set of encyclopedias from the 1880s and not having enough space to keep all of the books in my dorm room, so I began to rip out all the engraved images and sort them into folders. Even before discarding the first book in the alphabet, I began collecting texts that might come in handy in the future. I laugh about it now, but the collection of text occurred as early as my first collages, and even though I did not emphatically involve text in my collages until the 1990’s my first harvest of encyclopedia text foreshadowed my proclivity to use the written word.

Deciding what to bring to the residency was a big challenge. Beyond the dossiers on the specific collages I wanted to work on during the residency, I also brought with me things I thought I might need as well as peripheral support materials and a lot of reading materteral — what I affectionately call my “now playing” books — any books that I thought could connect up with any of the topics I was exploring.

I drove our electric car from Boston to Wilton, and the weight of the books and supplies was so heavy I had to charge the car battery three-quarters of the way there, when normally the same charge can make it to Queens, NY and still have enough to find a charging station there.

I keep both analog and digital folders on a great many interests. Some are object-related, but most are theme-based. Analog and digital dossiers exist for all 24 extent pieces in the LV series, and there are roughly a half dozen dossiers for projects I am currently working on. At present, there are 105 digital dossiers that are in various states of collection. What makes the Landscape Vernacular dossiers different from general folders is that they are hyper-connective; like the Internet, one subject easily links to another to form network or constellation of relationships. I like to call such hyperconnectivity information tag. I actively look for things that connect to a topic or subject that are not necessarily obvious connections but augment and stretch as much as inform the meaning of a given topic. Sometimes, what goes into a folder is so richly connected to other things that I have to siphon-off a portion of the collection to establish a new dossier. I collect multiples of a given artifact so that I can eventually be free to use whatever I need as I reach for it. And, I also use my dossiers as portable museums, intending to show the contents of the dossiers along with the collages themselves.

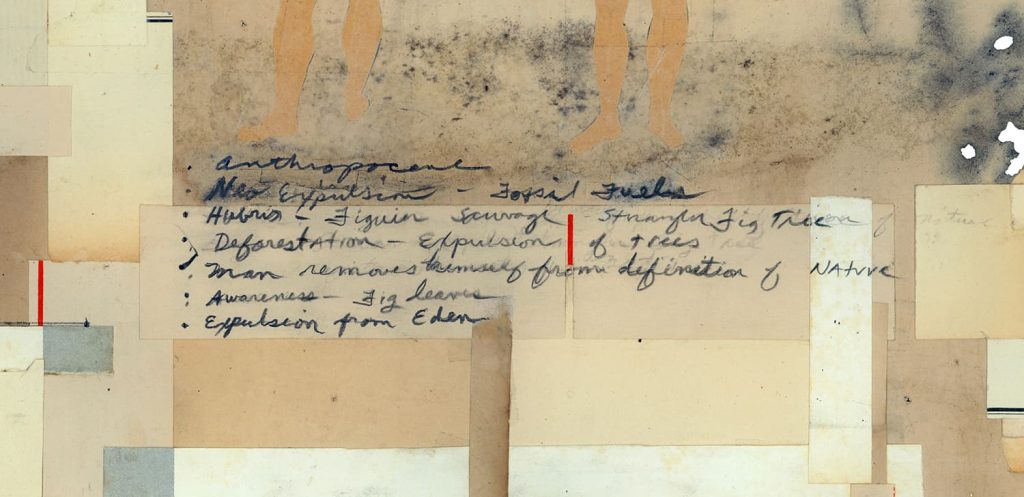

When I find an unexpected text or image that acts like a catalyst or otherwise galvanizes the contents of a given dossier, that is typically when I can’t contain my enthusiasm and have to start making a collage. Such was the case with siphoning off the materials that ultimately became Two Trees. I did not set out to make that piece at the residency. However, I recognized that my dossier was too big for one collage on “wilderness” and that I had enough material to address another theme within a theme. I made that collage start to finish within days of creating the new dossier. If I remember correctly, when you visited, I had created the new dossier for Two Trees only a day or two before.

AB

Research and collecting related documents and images seems to be only the beginning of the long process of creating each piece. You often go to great lengths to make, or remake, your own materials, “translating” or reworking primary documents. And all of this before the physical cutting and attaching. Though I’m sure it may vary by piece, can you walk us through the process of creating one of your recent pieces, from inception to physical completion?

TB

The entry point for each work in the Landscape Vernacular series is different from one to the next. For example, I have known I want to create an LV collage about white supremacy that addresses red-lining, and I already know I want to use Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America and juxtapose that with the chapter from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick entitled The Whiteness of the Whale, but I have been looking for a second catalyst that activates my spontaneous making process because, for me, Melville’s text was too quick of a connection, and I want something new or unexpected to work with. A recent purchase of Chromophobia, by David Batchelor, seems to have a promising possibility, but I have only just read the first few pages and yet have to collect the text that will ultimately catalyze my collected imagery and instigate its assembly. Redlining is a big topic with cultural complexity, so it is a project I am collecting slowly and carefully, and thus, that piece was not ready at the time of my residency.

The LV series will not be complete without acknowledging the Dutch origin of the word “landskip.” And this is yet another topic I want to get right. I set the goal to create a work about Dutch Holland at the onset of the LVseries in 2011 and I am still collecting for it. I know I want to involve Miguel de Cervantes’ Don Quixote and I even know the passage that I want to use from that book, as well as that I want this particular project to have an interactive component—a moving windmill that viewers can operate to reveal changing imagery. But the history is so interesting and interconnected to various things that it will still take a while before I find the catalyzing pieces that instigate the making process. I started reading The Nutmeg’s Curse, by Amitav Ghosh, about a year ago, and that book has already proven to hold the connective ideas I seek. The problem is that the book is so rich with potential for the LV series I am forced time and time again into a siphoning-off phase with every chapter. So there is yet some organization I need to do before I begin making the long-hoped-for collage.

One easy example to point out is that for one of the earlier works in the series, I created the semblance of an engraving for Caspar David Friedrich’s Wander Above a Sea of Fog. To create the look of an engraving, I divided the painting into zones and used a Photoshop plugin to accomplish the task—a process that took several days to accomplish.

Translating Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, (c. 1817-05) into the semblance of an engraving.

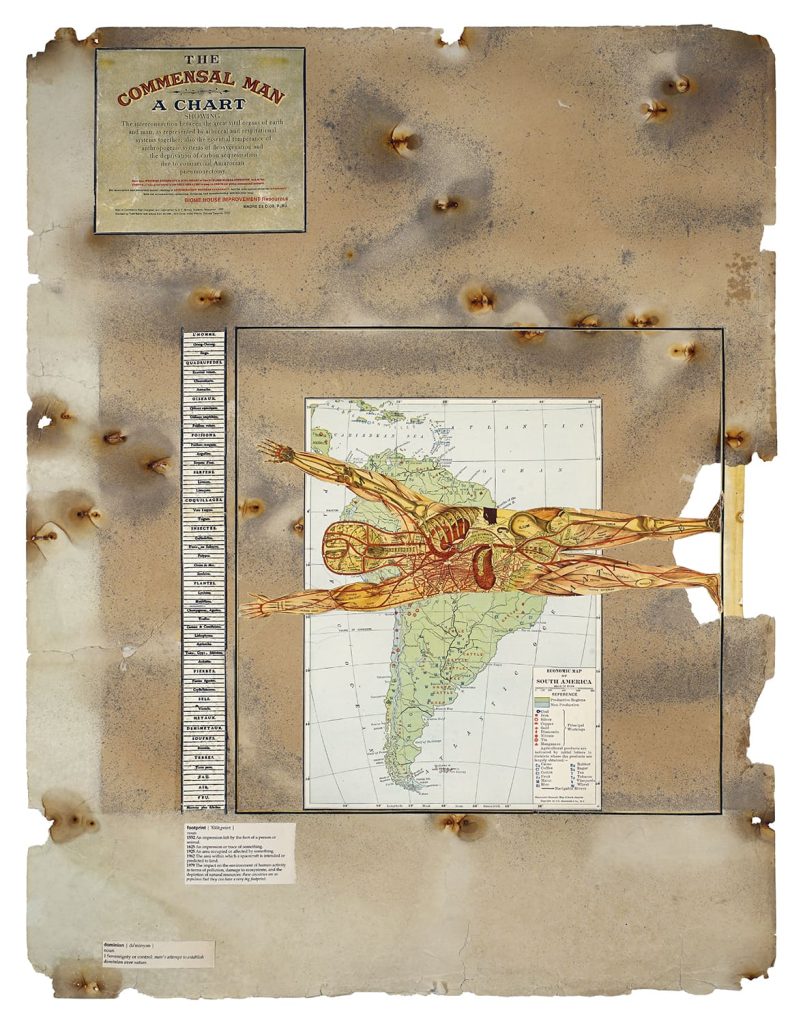

An example of the lengths I went to realize a single component for a work that I completed at the residency is taking the text from the original Man of Commerce Map and adapting my own redressed text. Well in advance to my residency, I spent 12 hours just getting the verbiage to echo the spirit of the original text, and then I digitally removed all the original text from the background using Photoshop’s clone tool in order to build the new text on top of the background as if it were the original text—that process was was also hours in the making. That was the first element I created for Surrender to Commensalism, a piece I submitted for an initiative that raised funding to save the Amazonian jungle of Peru, which I was only able to realize a digital facsimile of, but which was accepted in that show and subsequent publication. The work was initiated in my home studio as a digital work first, and then it became an analog collage. It was the piece on my desk in late June and was the first piece I completed while at Weir Farm.

Some pieces come together quickly, but take a very long time to cut. Such was the case with Dangerous Dualism and Magnificent Desolation. For these works, I had collected all the materials I wanted to use in a relatively short period of time, but as a high school teacher, curator, and parent, I lacked sufficient uninterrupted time to commence the construction of those pieces due to the intricate and time-consuming demands of each vision. The residency at Weir Farm was the right time and place to actualize such works. In fact, it was my desire to finish these pieces in particular that inspired me to apply for the residency in the first place. For years I had wanted to translate the haunting painting Moonlight, Wolf c. 1904 by Frederic Remington into a blank paper collage, and Weir Farm provided the time and space to actualize my vision.

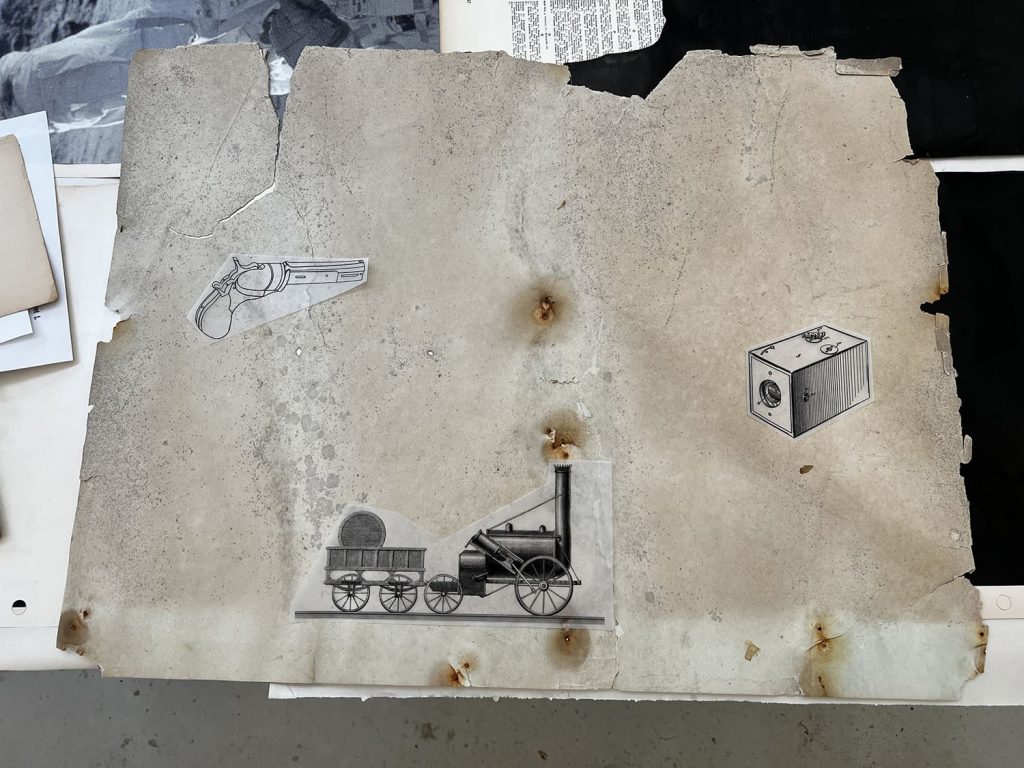

AB –We talked in your studio about the conceptual nature of your work and how this is balanced by the spontaneity of your process. There is a physical element to this, such as the surprise of a paper’s water stain that creates the look of smoke coming from a train engine. There is also the spontaneity of a convergence of events which create the sudden spark to begin a piece, like hearing Aldrin speak the words “magnificent desolation,” which ignited work on your piece about the moon landing. How do you think about these two aspects of your work? Can you talk about this balance of the conceptual with the elements of convergence and spontaneity?

TB –That is such a good example! It took me over a week, working from 10:00 am to midnight every day, just to cut the reflection in Buzz Aldrin’s visor. And yes, seeing a documentary on the Apollo missions alerted me to the lesser-known quote by Buzz Aldrin. The moment I heard his utterance, I immediately thought of putting the reflection of Earthrise in his visor while he was standing on the surface of the moon as if to transform his comment from being about the look and feel of the moon to a characterization of the state of the planet we call home. That idea was instant, and I have wanted to make it ever since, but to translate the juxtaposition of photographs into a blank paper collage would take months to realize. While I had accomplished the Photoshop work to digitally posterize the original NASA photos within days of having the initial idea, I did not have time to dedicate to the long hours cutting the project. Such work is painstaking because, for every color of paper I have to cut the same image and then release all the parts that need to be exchanged and they all have to fit exactly. It is time-consuming detail work, to say the least.

Once I have collected all the imagery for a piece like Gravity Roads, which only took a few weeks to assemble all the materials I wanted to use, as soon as enough time presents itself to start a new project, I look at my store of antique paper and select a page that seems to communicate the content in a compelling way. Aligning the paper stains to double as smoke from the locomotive was the deciding factor for selecting the page used, as well as setting up the composition for that piece. Such decisions are made with lightning speed. Sometimes, as soon as I place an image on the page and play with it, moving it around to select a composition, the available possibilities often dictate where a thing needs to go. In such cases, I just go with the flow and start cutting. In this way, even though it takes time to cut these projects, the decisions of where things go are a very quick affair. I sometimes act so quickly, I shock myself that I risk one-of-a-kind pieces of paper so readily. I would say I often work collage with the immediacy of a painter—which is how I was initially trained in the first place. I just make broad strokes with great speed—the rest of the time spent making an image is devotional and disciplined. I give the piece the time it needs to come into existence.

In this way I work incredibly fast while I am working incredibly slow.

Locating a conceptual element and collection time can also be slow. But by far, the slowest activity I engage with is the time it takes to read all the material I consider using. I am a VERY slow reader; I average about thirty minutes to read a page of a novel. I rarely read novels because my artwork demands so much reading time that I just have to let go of ever having that guilty pleasure. Reading books about history is an even more drawn-out process for me. I often have to reread a passage several times before I can grasp a meaning that is ultimately utilitarian for my work. I am a deep reader though and I mark the passages I read with post-notes so I can find what strikes my imagination. My family gives me Post-It notes as gifts, and I plow through them regularly! When I find material to use, I add it to my dossiers on a subject. I have redundant files—analog and digital, but often, unique materials are in one or the other respectively. One of my favorite features of an iPhone is that you can now select text in any photograph, so I am constantly taking photos of pages I read that have content I want to use. I could easily keep an army of assistants busy taking the passages of text I find interesting and putting them into a word processor for easy retrieval when I need them for my collages. So the collecting can take a while before I have what I need to make a work. Once I have a text, then I need to designed how it will be placed on the page and that requires a lot of measuring and planning. I often print on trace paper to visualize how it will look in advance of what I like to call “re-publishing.” When I republish, I either print directly on vintage paper or I involve a solvent transfer process directly on the collage in progress. As you can imagine, republishing is quite risky—I have to be very careful and thoughtful about each and every step.

Sometimes I start with an image and then look for a text that suits the image, and sometimes I start with text and then look for an image to juxtapose with it. While at Weir Farm I played with rust transfers and decided to pair my first experiment with a text I have long wanted to use: Silent Spring by Rachel Carson. I plan to cut out John James Audubon’s, American Robin, including the nest and branches and replace the overall shape with the rust transfer page I plan to cut off the “A” in “USA” so that it reads “Product of US.”

I came very close to making this piece but have yet to actually start cutting.

AB –Your works often feature two sides, like Joseph Cornell’s two-sided boxes and collages and Jess’ “Translation” paintings, which you’ve mentioned as significant inspirations. Through the incorporation of verso sides, you expose the intricate collage processes by which the works were made, including document repair tape, “paper band-aids,” “butterflies,” and “flying buttress repairs.” Can you elaborate on how this process contributes to the overall meaning of these works and sheds light on the creative process behind them?

The decision of what goes on the front versus what goes on the backs of these artworks seems crucial. Could you walk us through your considerations when making these choices?

TB –In some ways, the back of an LV collage is like a thing in the back of your mind—not quite in the visible light or in the forefront of your thoughts. Such ideas or connections are often more remote, or lying in wait—unconnected—but nevertheless present if not reminding, informing, or influencing.

Seeing Jess’ A Grand Collage at the Whitney Museum in 1994—actually, I saw the show twice—was when I first encountered his puzzle exchange collage, Deranged Stereopticon (1974), which got me thinking about puzzles and collages and the seed of that inspiration is directly tied to my use of interlocking collage. Jess’ Translation paintings are truly bizarre in how they are made. Each of the thirty-two paintings in the series are translated from black-and-white imagery into unusual color combinations, painted as though intermittently distributed objects like rocks were somehow attached below the surface of the paint. The paint itself is built up into thick impasto plateaus that rise well above the level of the original drawings, which have a coloring book feel in their line quality, are thus rendered like trickling gullies below. On the backs of his paintings are selections of text that enhance and inform the rectos. Seeing his Translation paintings cemented my interest in producing series work and exploring how text can extra-illustrate.

burnished interlocking collage, 25.875 x 20 inches

[verso]

My LV collages, like puzzles themselves, are seamed, single-surface composite images once assembled. And like puzzles, the individual pieces are easily separated if moved or handled. As I evolved the techniques to make what I used to call a “puzzle-piece-fit collage,” I developed various ways to attach the cut pieces on their verso sides so that the works could be picked up and handled, and ultimately, framed. One of the things about making interlocking collages is that sometimes the cuts are so well dovetailed that you can’t necessarily ascertain they are even cut in the first place, and I decided to develop various ways to assemble them so that the cut pieces could be appreciated from the backs. I use document repair tape so you can see the cut pieces, and for less crucial imagery, I use what I call paper band-aids to cover the seams. Butterfly band-aids are used when the piece of paper I selected is not whole to begin with, but I am fortunate enough to locate the missing pieces that allow me to reform the sheet, more or less, to its original size. In these instances, I use decorative joinery that also points to medical joinery—some cuts do not need sutures but demand another kind of support. (See: Two Trees, for an example of butterfly joinery.) When I leave holes in the parent pages need additional structure so protruding paper peninsulas won’t otherwise fold or tear when handled, I utilize a flying buttress repair technique that makes the paper band-aid visible as the repairs extend across the gaping holes. Surrender to Commensalism uses this form of repair; I have the missing piece of paper by the feet, but wanted to emphasize the “footprint,” so left the missing piece out of the work.

As the backs of the collages necessarily get built up, I often make drawing decisions, choosing various shades of vintage blank paper to offset other shades already there. I really enjoy making such incidental drawings, which are much more in the service of restoration than they are to art-making per se. In this way, I allow my work to have a kind of non-human-made quality or an otherwise accidental-nature-made quality. I have long been enamored by frescoes with missing chunks of plaster, indiscriminately redacting visual information, often crucial to the overall imagery. Studying nature, in this way, has given me a kind of roadmap to be rather bold about making repairs. I refer to this way of drawing (collaging) as brutal-incidental. As I evolved the series, I quickly realized I loved making the backs as much as the fronts. But the dedicated activity to make all these repairs I liken to acts of stewardship and caregiving.

The first pieces in the LV series were traditionally framed, but I lamented mounting them to mats because you could not see the interesting versos. The 6th piece in the series, Proportions and Table Manners, was a more complex work and had a lot of information I needed to include. As I was working on it, I realized there was a story I wanted to handwrite on the piece that I did not want to put on the front.

verso, center detail

I thought about Joseph Cornell’s handwritten and typed notes on what music he was listening to when he made each piece, and what constellation informed the front of the work, which he often collaged to the backs of his collages and assemblages, and I decided to try to make a piece with a back that informed the front. The series was so young I didn’t even consider how to frame a two-sided piece at that point. But two days after I finished the piece, I was invited to be in a 50-year anniversary show in honor of select European Honors students who attended Rhode Island School of Design’s Rome program, and when I spoke to the curator about the two-sided piece, he asked how viewers could see the back. On the spot, I offered to create a frame that could hinge open. He loved the idea; I made the first frame in less than a week to get it to the opening in time — that is why that frame is so rough around the edges.

burnished interlocking collage, 30.25 x 13.125 inches

[verso]

burnished interlocking collage, 26 x 20.5 inches

[verso]

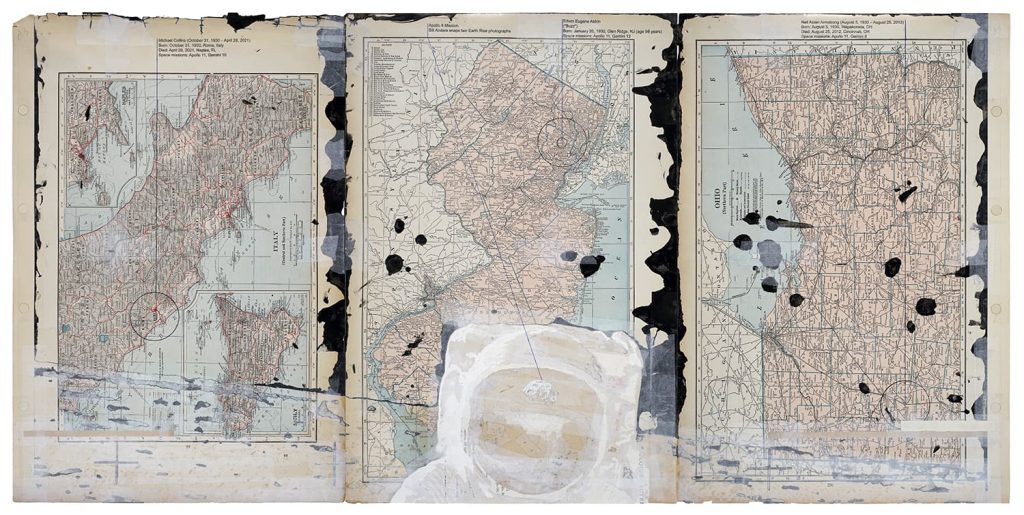

Eleven of the twenty-four collages in the series have folding frames to view the versos. Most of the time, the backs have ancillary and/or supplementary imagery, which allows me to simplify the frontispiece imagery. In one rare instance, the collage, Dangerous Dualism, has no text on the front so as to confront the viewer with their own uninfluenced ideation and associations.Due to its size and shape, Magnificent Desolation does not have a folding frame, but the verso side nevertheless pays homage to Apollo 11 astronauts. I selected a map of each astronaut’s birthplace and footnoted William Anders’ Earthrise photograph.

burnished interlocking collage, 20 x 13.5 inches

[verso]

AB

Though your works deal with large-scale global problems, there is a poetry to the arrangement of words and images, and a sense of care that comes from your considered approach. I wonder how you see yourself and your sensibility within these works and how that adds to the meaning of each piece.

TB –Thank you for this question, Andrea, and thank you for appreciating this aspect of my work. While it is a cliché to make a beautiful thing about an ugly subject, I try to overcome the trope; I hope my devotion to every aspect of the work circumvents the problems with the ages-old formula. I want the work I make to unfold slowly, like a realization that clings sweetly to the mind, once illuminated, but then yields yet another illumination due to the double and triple entendres I play with when combining images and texts. For example, the title of the work Terror Follows Territory is both a truism and an alphabetical dictionary arrangement of definitions. I want to be surprised when I look at my work, even though I made it. I hope to accomplish this by addressing each image on multiple levels simultaneously—juxtaposed images and texts that inspire associative linking, poetic transference, emotive awakening, recollection that yields questioning, or logical thought amidst the unexpected. Because I prize emotion, association, memory, and concept equally, I try to balance them all in any given work. With so much to contend with in the LV series, I tend to counterbalance the abundance of entry points with a feeling or illusion of space. Thus, the blank page at times acts like an open sky that goes in every direction as far as the eye can see. Some topics are so dense that, at times, I feel the need to deny the elegance of space, as in the piece Terror Comes After Territory. But all the new works have a sparing quality that I hope speaks to the beauty and splendor of the world we inhabit, and my belief in the human project to redress our behavior that harms our most precious resource: home.

I have the deepest belief in the human project, but we really need to work in a more collective spirit now that we have invoked the Anthropocene era, and this, above all, is why I consider myself a steward of nature and humanity.

AB –There are many things that collage as an art form can do very well, many of which you’ve outlined in your writings and previous TWS interviews. Looking at and talking about your work over time, it is clear that one of the things that your work does is present materials that bring issues and ideas from the past back into awareness, specifically things that need more attention and that haven’t been fully investigated. What do you think about this aspect of collage? And do you have a name or definition for this aspect?

Quote, cite, reference, copy, sample, cover, ekphrasis, phrase, refrain, renew, recycle, reuse, regenerate; like water, collage conforms and adapts to any location, situation, or condition. Collage is the preeminent shapeshifter. When collage brings something back again, it just means we are not done thinking about or experiencing that thing. Collage is the art of collection, even if only a single element is brought to hand, eye, or mind. It only takes one collector to remind us of a thing. We all stand on the shoulders of immeasurablecontributions to the human project; to be reminded of a previous contribution is not only a gift memory it’s also a gift of instigation. It is a thing of contemplation and beauty to see again the old thing as yet still relevant because, in the context of now, and concert with another things the original thing becomes something else: a hyper object. One object plus another object becomes a third thing. Collage is always new. My word for this aspect of collage is “unfoldingobject” — a work that reveals layers of meaning over time.

This is the interview’s second part. If you haven’t read the first one, follow this link)