In this exclusive TWS interview, Barcelona-based artist Gina Giménez shares her creative journey. She explains how a “flawed” Mondrian piece inspired her to embrace imperfections in her own work. Giménez also discusses her unique process of using old maps and science books as inspiration, transforming them into art. The conversation offers a glimpse into her world of constant curiosity and artistic exploration.

TWS – What’s the first thing you’d like people reading this to know about you?

GG – Nothing specific, because one of the beautiful things about art is that everyone can think and know different things about me. And it happens: there are those who think I’m simply a painter, others that I’m an important international artist, and there are those who see me as an art teacher who also paints. It doesn’t bother me at all; it’s all fine with me.

Now, if I had to choose, I’d simply say: an artist who works every day and who no longer knows how to do anything else but art. I’m at that cool point of no return.

TWS – Which is the earliest moment you recall that art became part of your life?

GG – When I was very young—8 years old—you could sign up for basketball or painting in after-school activities, and I signed up for painting. I think it had a lot to do with finding a safe space for myself, because I was very shy. In team sports, there’s pressure; you depend on the team. In painting, there was no pressure; I was alone. I found a place of safety. I was wrong, of course, because now I compete with myself, which is much worse.

After that I simply kept taking classes, doing courses, and I never got bored. When I had to choose what to do after high school, my parents didn’t want me to go to Fine Arts; they thought it was “sex, drugs, and rock and roll” and that I wouldn’t find a job. They told me, with all the best intentions, to pursue a “serious” career and paint later. At that time, when I was already reading art books and artist biographies, I saw that “serious” artists paint seriously, but they don’t do anything else.

So I tricked them, saying I was going to study biology, which I also liked. The Faculty of Biology was next to the Fine Arts, so I signed up for Fine Arts with a lot of anxiety about passing the entrance exam, since if I didn’t pass it, I wouldn’t have a spot in either. When my parents found out, I cried so much that they told me to try Fine Arts, that it would be okay.

TWS – Do you remember the first graphic piece or work of art that caught your attention in your life?

GG – I don’t know if it’s the first, but there’s one I’ll always remember. It was a small Mondrian piece I saw in New York, I don’t know if it was at the MoMA. I was about 20 years old, and until that moment, I had only seen Mondrians in books. When I saw it in the museum, I saw that the same thing that happened to me happened to it—and I don’t mean that I felt I was as good as him—: there were marks, imperfections, it was “badly painted.”

When you see a reproduction, it looks fake, almost digital. But in the museum, I saw that the paint had bled a little when the tape was lifted, and that moved me. I thought, “This wasn’t made with just the head, but with the hands and with all the soul.” Until that moment, I saw his pieces as very cold. From then on, I think it helped me overcome my fear of being clumsy in my work. To not try to hide “mistakes” and to use chance by incorporating elements like ink smudges—which happened to me as a child in technical drawing. I began to feel that the work was not just about placing things, but about creating an atmosphere where the support is part of the piece.

TWS – You were going to sign up for biology, and your work recovers things from the sciences, geography. Did you already see something interesting in them back then, or is it something you’ve picked up over time?

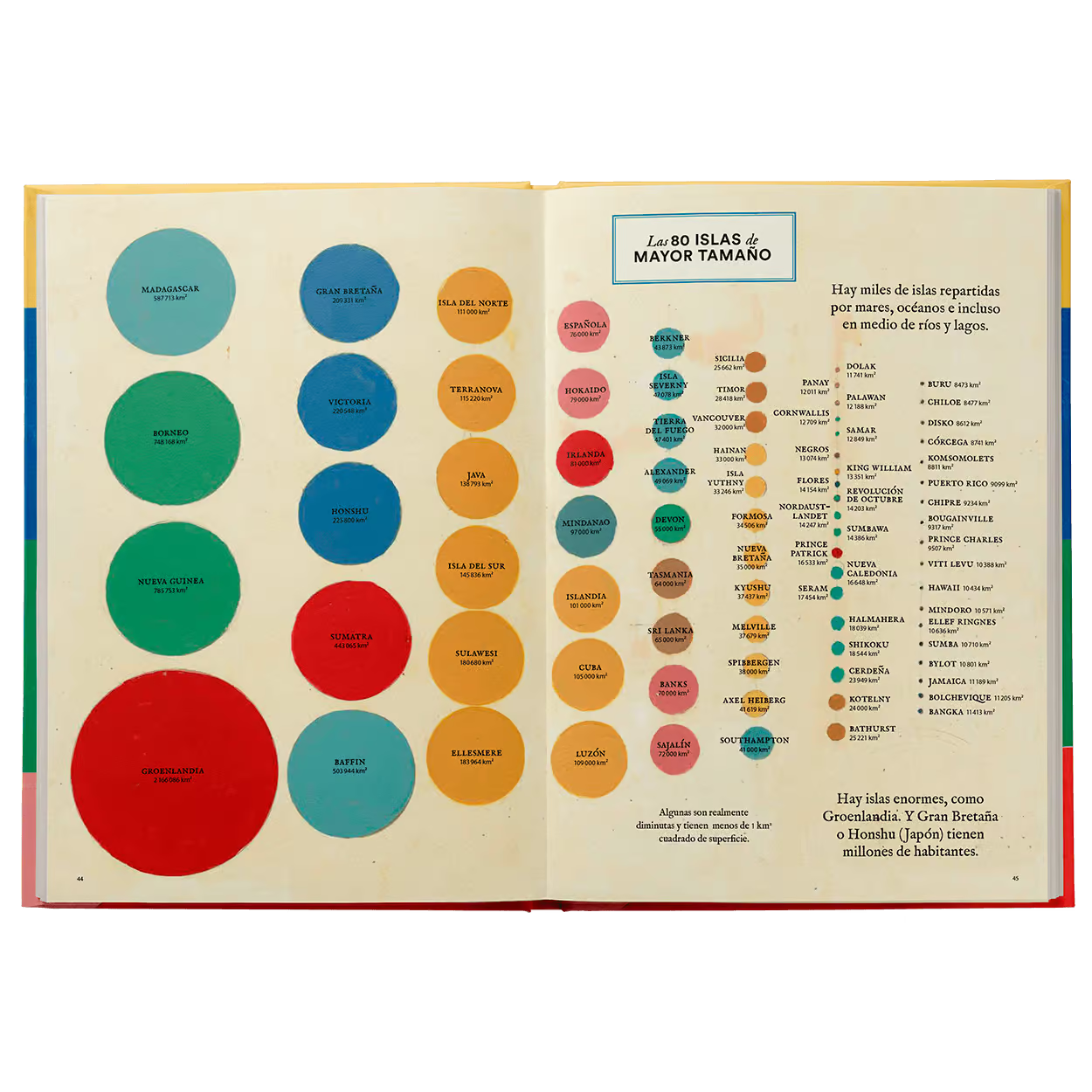

GG – I’ve always liked it. But in a way that I now recognize as aesthetic. I remember looking at my parents’ atlases and geography books. I was fascinated by the placement, the diagrams, the shapes—organic and synthetic. Although I’m dyslexic and didn’t understand anything, I spent a lot of time looking at them. I also remember looking at biology books, about DNA, without understanding it. Now I’ve discovered that it was probably those graphics that I loved. I like the representations that human beings have created to try and explain all these things in a pedagogical way—things that are often difficult to understand because they’re abstract or complex concepts that are hard to represent visually.

Back then, I thought science was my thing, but over time, I saw that, because of my dyslexia, I wasn’t good at it. Art and dyslexia get along better; it doesn’t matter if you mix up right and left. Now I use these graphics, images, and statistics, taking them out of their context and creating my work from them.

TWS – There’s an interesting relationship between science and art in your work.

GG – There has been a great link between both science in art and art in science. I think, for example, of early cartographers and botanical illustrators. We call their work “scientific illustration,” but these are actually authentic works of art. The same thing happens in medicine—we have doctors who made drawings and notes that are truly impressive.

An exhibition of Rubens just opened yesterday (in Barcelona, in May 2025), and there was a notebook with anatomy notes where you could see that fascinating mix of art and science. The “la Caixa” Foundation also had an exhibition where they showed some small drawings by Ramón y Cajal (a Spanish Medicine Nobel Prize Winner from late 19th and early 20th century) … and you don’t understand anything, but they’re marvelous! And the interesting thing is that they were exhibiting them as works of art; they had transcended science. Because they are probably obsolete—what they explained in those papers has already been surpassed, right?—so they can go directly to another stage, another place. And that place can be art.

That also happens in design. I think, for example, of the Russian avant-gardes where many posters were created for political or social reasons. And of course, those pieces were born with a very specific function, but now they’re pieces of art—and authentic marvels.

TWS – When you take a map or a geographical element and you remove its symbology, what’s left in your work?

GG – When I remove the legend that makes it readable as a map, what remains is an abstraction. But it’s not entirely abstract because your mind recognizes what it knows—and in my work, it half-recognizes something familiar. So what’s really left is a mystery, a question. It’s a half-abstraction. Depending on the graphics, they can be read as landscapes or a cosmography. They’re not impenetrable abstractions; they’re open but they maintain that link to geography –or cosmography.

And then everyone interprets the work in their own way. I love how children see ice creams, and an astronomer sees a star. I never contradict them. Each piece has many layers. One thing is the artist’s intention, another is how it reaches you. The first layer is visceral, like the children’s. Then, you can go deeper. I want my work to arrive like that, with that first direct relationship.

TWS – Have you heard incredible interpretations of your work from viewers?

GG – Yes! It’s the best. I love it.

Sometimes you’re standing nearby, quiet, listening to someone say, “Let’s see what they say…” And there are interpretations that leave you speechless: “What has this person seen here?” And for me, that’s the magic. I never contradict them. Because we all do that with art.

Many times we see a work and we think: “The artist probably wasn’t thinking this, but I get something else.” And that’s valid. As you well know, more than trying to understand what the artist wanted to say, the important thing is how it reaches us. Every work of art has many layers.

If we see a work by Miró, we already know when he made it, why he made it, and we can easily access that contextual layer. But we still have the first one, which is the most visceral: “I like this little line,” even if for him it was a universe, or perhaps nothing.

That first layer is fundamental. Then come the others, more profound, that enrich the experience. But I’m especially interested in my work reaching that first layer. That’s why I go back to children. They get that first impression. They won’t say: “Oh, you’re in a pink phase after a blue one…” No. They say: “I like it” or “it’s ugly,” and that’s it. And that’s perfect.

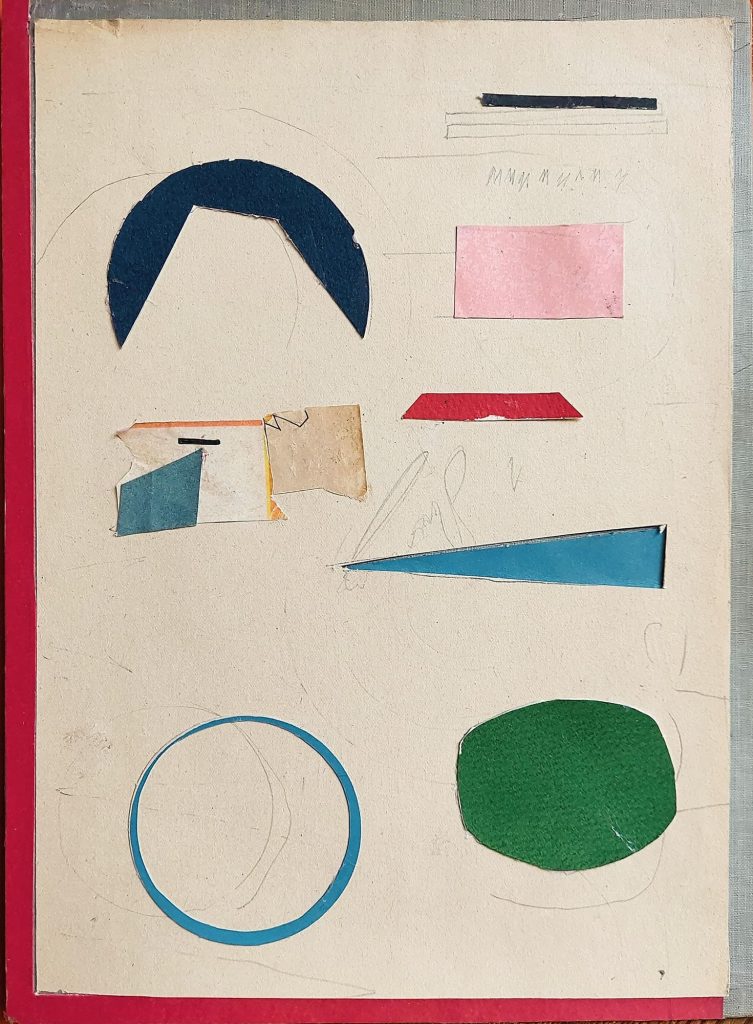

TWS – You work in series. How does a series start? That is, what’s the starting point?

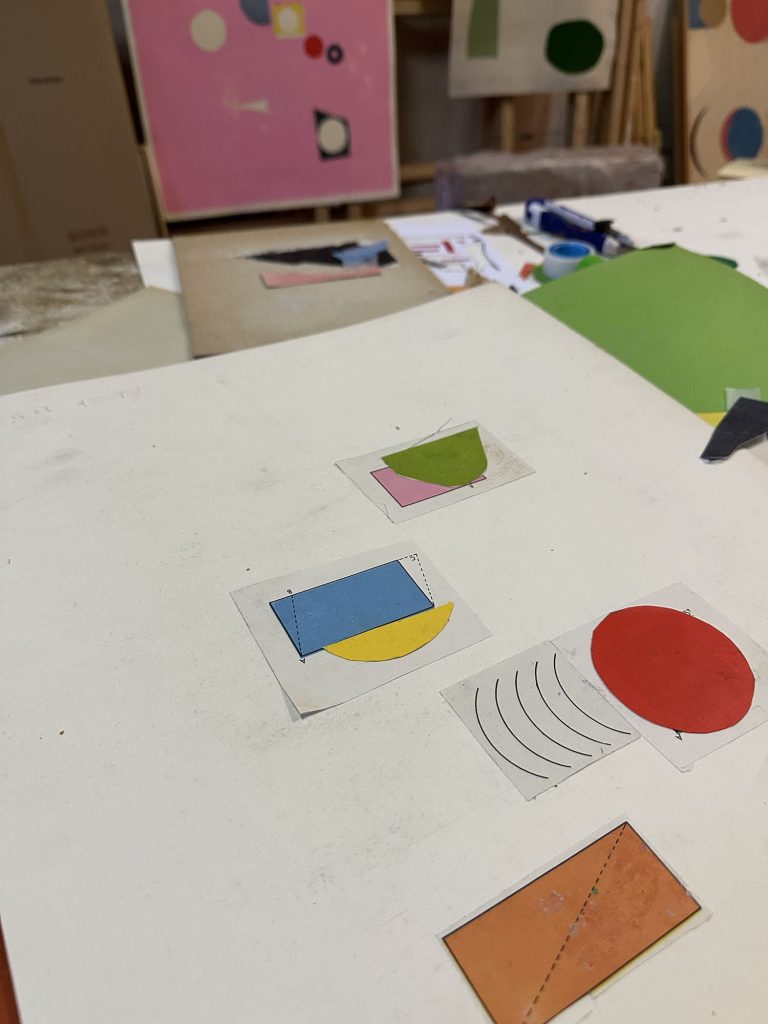

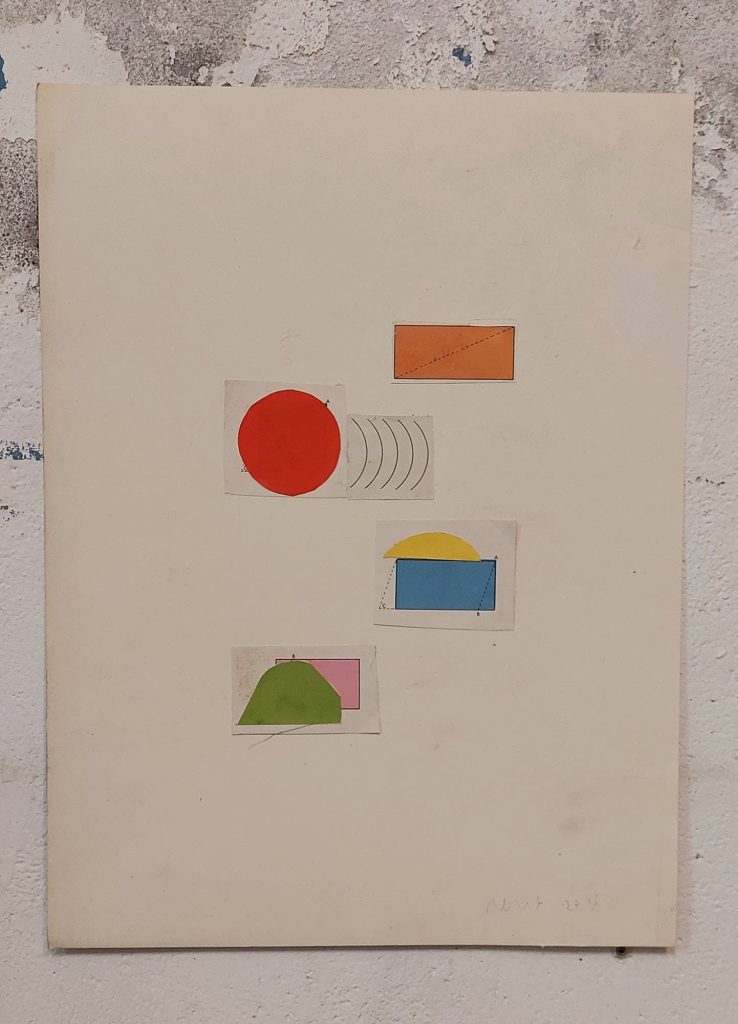

GG – Sometimes there’s nothing big or important. It can be something totally random. For example, in these latest works I’m doing on landscapes—which are titled Pensar un paisaje (Thinking a Landscape)—the starting point was the casual encounter with some children’s craft books from the 1950s. In them, there were elements to cut out and assemble a landscape. But what surprised me is that the landscape was already drawn by the author, and the children simply had to glue the elements where they belonged. That is, they were crafts, yes, but zero art. There was no space for critical thinking.

I remember when I saw one of those pages, I thought: “This is a marvelous landscape.” What I did was very simple: I photocopied the page, cut out the elements, and glued them. And from there, a world emerged.

Sometimes it’s very simple. Everything can start by opening an atlas or any book. I provoke those encounters: if there’s an old bookstore, I’m there. But I’m not looking for first editions, but school books from the 60s, for example. I’m interested in how complicated concepts were explained with images that were often very difficult for children to understand. When I was studying, there were already photographs, but in those books, there were extremely simple graphics.

Many times the trigger is simply a color. I have a certain obsession with colors. It’s not that I like some and not others, but about finding that right tone, that exact nuance. Sometimes I get obsessed. And that’s why I collect colored papers. I remember Josef Albers’ book Interaction of Color, which recommended doing the exercises with papers because the tone always remained the same. And I thought: “Of course, that tone must be kept.” In my case, they are old, faded tones that are no longer manufactured. So a small detail like a color can also start a series.

The same thing happens to me with supports. I don’t usually work on a neutral support, like a blank sheet. I need the support to already be part of the work. Sometimes, that support is also the click that sets everything off.

When does the series end? I don’t know that for sure. I do know there’s a very clear feeling: when I start to get bored. And I say “bored” in the sense of feeling that I’m repeating myself, that I’m no longer discovering anything new. At that moment, I think: what am I doing? But a series can last a long time. And it can come back, even years later, with another form, another perspective. Because you have also changed. You have gone through other places, other works, other thoughts.

TWS – And of all this process, is there a part that’s your favorite? That stage where you say: I’m good here, I enjoy this the most?

GG – One of my favorite moments is finding the click that allows me to see something special in what I’m doing. Sometimes you’ve spent three days with a cutout image, a drawing, a photo… and you’re there, waiting, not yet knowing what to do with it. But you know there’s something, until at one moment you see it, and there are a few seconds of surprise that are incredible. I don’t see what I’m doing until I step back a little, look at it… and suddenly: surprise! It doesn’t always happen, of course. But every once in a while, it does. That first click, that moment of “there’s something here,” is what tells me that there’s a path to travel. Maybe I don’t even think about a series at that moment, but then it becomes one. Because I need to go deeper; I can’t stay on the surface.

But of course, when time passes and that click doesn’t appear… there’s anguish. You go to the studio, you look at what you have, you move things from right to left, but it’s not there. You don’t see it. And over time, you learn to live with that, to wait. But it’s hard.

Then comes another important moment: the first piece of the series. That first piece comes out with freshness, and then everything gets more complicated. Because, of course, that first magical gesture can’t be repeated indefinitely.

Every time I finish an exhibition, I feel a kind of depression. Something like a total void. I think: “That’s it. I’ll never be able to do anything again.” I tell myself: “This is all I had; I can’t go anywhere else.” And then I calm down, of course. I continue. But that moment is there. Always.

TWS – The idea of a series also implies a global presentation. What role does the exhibition space play?

GG – Before, when I worked with galleries that would ask you: “How many paintings do you have? 20, perfect, we’ll hang them,” I felt that made no sense. I needed there to be a global reading, a journey. That’s why I left those galleries and looked for other ways to present the work. Now I work more from a site-specific perspective, and that also changes everything.

My work has a lot to do with the space now. I can’t conceive of the work without the space. The work is disorganized until you place it there. I have to go see the space, feel its atmosphere, light, color. It’s like another support. Each place is different, and that determines which works and how they will be presented.

TWS – You have works of very varied formats. How and when do you decide on the format?

GG – Sometimes it’s conditioned by the space. But often, the format is decided by the work itself. Each piece has its format. I guess it’s because I’ve been working for so long that I see it automatically. There’s no formula, but by working, you mentally “see” the work or imagine it in a certain format. Although I also make mistakes; sometimes you want to make a small work that you love large, and it doesn’t work.

I’ve always thought that the beautiful thing about art is that kind of uselessness it has. And its greatness is precisely there. So, why on earth are you copying this small work, making it large, freehand, when you could do it digitally, on a large scale, very clean? For me, the greatness is there: in that nonsensicalness, which is sometimes absurd, yes, but also necessary.

But if you think about it, it’s something anachronistic for the time we live in. We’ve already gone through everything in art history: all the “isms,” conceptual art, performance, video art… And you reach a point where you think: “Are you seriously cutting things out and painting?” Well, yes, I am.

And it’s precisely that anachronism that gives it value. Beyond the poetry, beyond everything else, there’s that uselessness that makes you think, that forces you to ask yourself: why is this being done?

TWS – Your work has that “perfect imperfection.” How do you handle materials and their imperfections?

GG – I like there to be a trace of the past, a preexisting history. Many times, that trace is the click I need to make a piece or start a series. I save many supports or materials until I feel that the time is right. I like to work with that information that was there before I arrived.

For example, the supports I have here are not canvases; they are felts from a printing press. I bought these specific ones from an engraver in exchange for paying for his new felts. They had stains from more than 30 years of use, and I used them as a support and passed them through the printing press again with inked shapes, using the existing stains. This series is called Sobre tierra abonada (On Fertilized Earth) because they have 30 years of artists passing through. The stains, the rust, the tears are part of it.

It also happens with the old papers that I collect. Some I find on the street, others aren’t old but they have a color I like and I take them. Sometimes I’m in a fruit shop and I say: “Can I take this paper?” And they look at you funny. Until you say: “It’s just that I’m an artist.” And then they look at you even funnier, but they say: “Yes, yes, take it… who knows.”

TWS – Speaking of accidents and related to the idea of “taming accidents.” How much of your process is planned and how much is letting go?

GG – My process is very little planned. It’s not that I haven’t tried to plan it; I’d like to be able to do it a little more, but it just doesn’t work when I plan it. So, how much is accident? Quite a lot. When I work, I let myself go, and many times I get angry with myself because I’ve gone too far: it’s too dirty, too stained, not right… and sometimes I even ruin it.

But it’s not about seeking a kind of purification, but about having a sharp eye to recognize that moment when you say: “There, yes, that works.” That’s why I often save stained supports or papers, or with brushstrokes I made at any given moment, perhaps just to test a color while I was painting.

So, really, there’s very little planning. What I’ve done is adapt and stop obsessing over “why does everything come out so dirty?” And when I say dirty, I don’t just mean literal dirt—although that too—but, for example, a line of drawing that no longer fits because I’ve changed the arrangement of the elements. That line is still there. Sometimes I try to erase it, if I can. It’s a matter of composition, of rhythm. I guess there’s a balance between that “dirt,” that accident, and what ends up composing the work in its entirety.

And I want to think that the magic of art is there. Because if there were a formula, we would have already written it in a book to hand out. But there isn’t one. And it’s true: there isn’t.

TWS – Was it difficult for you to learn to accept mistakes as part of your work?

GG – Yes, it was difficult. Until at some point I said: “Well, whatever, forget it, it’s just how it is.” Because this is part of my work. It had happened to me, for example, to exhibit somewhere and have a collector say: “But this is very dirty, isn’t it?” And for me to think: “See? Of course, it’s dirty.” Although it wasn’t really that dirty, but he saw it that way.

And look, I also love seeing a perfect work. It’s not that I don’t like it. When I see a work with the impeccable white of the paper, the perfect edges, and only a small gesture or a minimal intervention… I think it’s marvelous. But that doesn’t happen with my work.

It was quite hard to accept, but now I try to let myself go a little more. It’s not always easy. Sometimes, since there’s no planning, not everything comes out well. I remember a four-meter canvas that I didn’t get to present because the accident that happened on it didn’t work; it didn’t contribute anything. But well, it’s part of the game. You take a risk. And I realized something: since I couldn’t remove what I didn’t like, I started to enhance it. Sometimes I cover it with a square, or I turn it into something else. It reminded me of those old grandmother’s sheets that had patches. So I make a patch. And you can clearly see that it’s a patch. Because I didn’t like that accident, but I can control the patch.

TWS – Do you recognize a feeling of nostalgia in your work, maybe because of the materials or the base images you use?

GG – I understand that it comes across, even though I’m not actively looking for it. I think the feeling of nostalgia has to do with my admiration for certain works, certain artists, certain pieces, and how they have reached the present day. On the other hand, by using the materials I use, part of that nostalgia is already in them. That paper, when I use it, was already like that; I can’t do anything else. I could avoid it, I could paint it white and cover it up, but no, I want to preserve those marks of the passage of time. I’m using that support and those images because they interest me at that moment, and that color interests me at that moment.

And there’s the obsession again, with both the support and the color, with those old tones. It seems like a constant struggle to try to achieve those tones. And it’s impossible. There are times when I spend hours trying to reproduce them, and I don’t succeed, because we’re talking about a paper that has lived for fifty years, that has been exposed to light, that was printed at the time, and whose color has been changing. Many things have happened to it.

In the case of the fabrics I’m using now, they’re not old, but they already have accidents. They’re recycled fabrics, and sometimes they have some defect, like a badly sewn thread or some mark. That also fascinates me. I’ve realized that I was bored working on white fabrics, the ones they sell in stores. The first thing I did was dye them a certain shade, but even so, I didn’t enjoy it. It was a support without play. Now, yes, now I play with that support.

For example, this other fabric was collected from the street. It’s an old burlap. It’s not prepared; there’s no priming. I paint some images on top, but of course, it already has stains. It already has history. And I understand that that generates a feeling of nostalgia, although I’m not entirely conscious of it. No, I’m not.

TWS – It gives the impression that you’re trying to “tame” what you have around you.

GG – Yes. Yes. Now I’m working—well, for a while now—with book covers. They already come with a specific format, and I like that a lot. I accumulate them; I save them until the possibility of using them arises. It’s about finding a cover that has already lived things. I like that there’s already information there before I intervene. That information, that time… you call it nostalgia, and many people do too, but I don’t call it that. For me, it’s information, it’s memory, it’s history.

TWS – Collage is recontextualizing objects with history and putting them somewhere else. Do you see your work as collage?

GG – Exactly. That’s exactly what I’ve been doing. You take objects—graphic elements—you take them out of their original context, you place them somewhere else, you join them with colors that aren’t their own… For me, that’s collage.

Collage is the world we live in, entirely. Today more than ever. With globalization, there’s an absolute collage of everything. It’s impossible not to see it. We take things from one place, we put them in another, they’re decontextualized. You see it even in the products we buy. I think: my grandmother would never have received a t-shirt made in China, but finished somewhere else, and transported by another company.

The thing is that for a long time, collage has been considered a minor art, like: “Oh, what a fun idea.” And that perception has reached us today partly because of how art has been taught to us. And the idea of collage is something else: It’s about taking things from many places and building a different universe. Or many different universes.

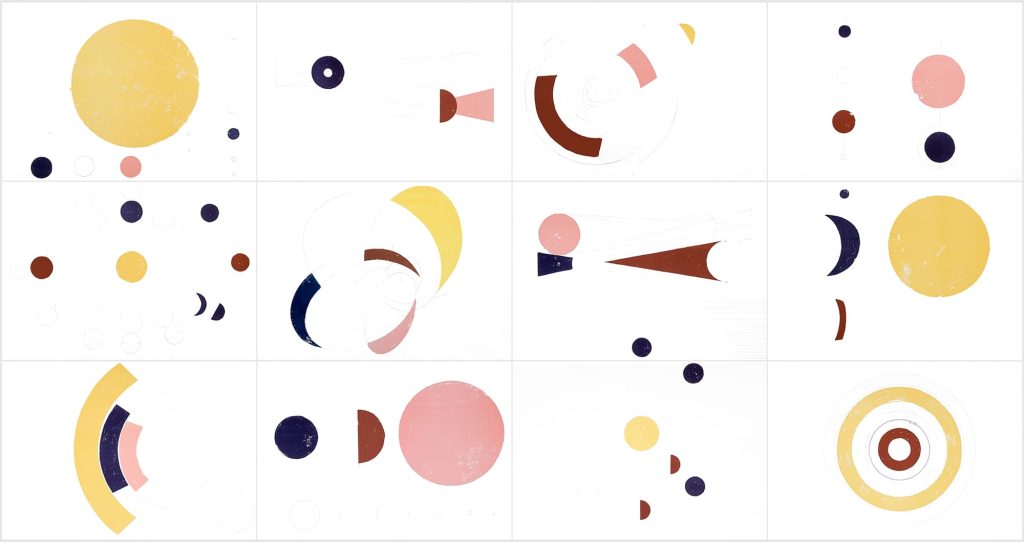

TWS – Tell me about your book Geográficos. How did it come about?

GG – The creation process in this case was very clear. I met the book’s editor, who already knew my work and liked it a lot. She said to me: “Could we do something with you? Would you like to make a book?” She first proposed something for children or young adults.

And the first thing I replied was: “No, no, no… I’m not an illustrator in that sense; I won’t be able to build a traditional story.” I told her: “If I make a book, it will be more like Bruno Munari.” The editor said: “Okay, whatever you want.” And I said: “Well then, I’d like to make an atlas. But without maps.” She accepted right away. She was making it so easy for me that I thought: “This is a trap, for sure.”

And I started working in a very natural way. It was like closing a circle; doing a 360-degree turn. If in my work I took images or graphics from old geography books and extracted the legends, taking them to contemporary art—it was a kind of visual translation—for the book I collected the works made from those images and updated the data. So, the gesture was exactly the opposite: to add informational content back to them, without losing the artistic part.

I’ve said it in some interviews: it was also a tribute to the first geographers. Making a geography atlas seemed like climbing an eight-thousander: a crazy idea. I couldn’t do it alone. That’s why, in the book, the graphic part is mine, but the theoretical part, the data, is by a geographer.

I also found that contradiction interesting. It made no sense to make an analog atlas, without maps, with works that look like geometric abstractions… in the middle of the 21st century. Digitally, absolute marvels are made: statistics, visualizations, real-time data… That “not making sense” was precisely what gave the project its meaning. It turned it into something different.

I said to the editor, Mireia: “We’re going to make an atlas, but there are already many.” And some are beautiful, made digitally, very polished. But this one wasn’t going to have anything digital. You would see the paper, you would see the stroke, and you—I said—are going to put all the necessary data so that, in addition, it’s a popular science book. Not just illustration.

And surprisingly, she said yes.

But that’s not all. Once the works were finished, scanned, and sent to the printer, I took the originals and exhibited them at the Museo Patio Herreriano, in Valladolid. They took up an entire wall. No one understood what they were seeing. They said to me: “How beautiful this is… are they circles?, are they countries?, what is it?” No one knew it was part of a book that was still at the printer.

I really like that constant back and forth. Even within the same book, sometimes you have to adapt, to put the purely artistic part aside a little in order to include the data, so that it’s understood. We wanted it to be informative, so we made small concessions. But then, from there, I’ve taken things that came up in the book and taken them back to more personal works.

And in the second book, the one about Mountains, exactly the same thing happens. It’s based on the idea of talking about all possible aspects of mountains, but it’s still a very simple and very personal work. And honestly, I feel very good working like that.

TWS – It gives the feeling that you’re in a territory located between many practices: painting, engraving, printing, collage…

GG – That’s another very controversial topic: starting to put definitions on everything. Everything has to be defined. And in art, even more so: What are you? What do you do?

I still understand that question when it comes from someone who isn’t in art. But now I’ve found a way to answer: “Do you have Instagram? Yes. Well, look at my Instagram.” Because it’s impossible to explain. How do I explain what I do to someone if they’re not in the art world? If I start with “I work with geometric abstraction, but it’s not so geometric… and it’s not so abstract either, because there are figurative elements that are understood… but they’re arranged in space in a random way to create a new universe, a landscape…” And you see their face and you think: “Ugh.”

It’s difficult. Especially for someone who comes from a tradition of landscape, still life, figure. That was easy. But this is something else.

I think one of the big problems is art education. We still teach the same thing: from the Renaissance to the Modern Age, and we never get to contemporary art. It doesn’t matter. And it does matter. Maybe we should start with contemporary. If we understood contemporary art, we would understand everything else. Because contemporary art exists thanks to all of art history. Nothing comes from nothing. No one invents anything completely new.

TWS – Do you feel comfortable in this mixed profile?

GG – Yes, I do. Although I think it can be a problem for galleries. I need to work this way, but it’s not always understood. From the art market, it’s easier for them to pigeonhole you: if you’re a painter, you paint; if you do photography, you take photos and that’s it. This in-between space is harder to accept. But I feel very good in it.

I use the technique that I feel each piece needs. I like that game, that spirit that appears when I go to an engraving workshop and experiment there. It has something magical, like analog photography, where you never know exactly how it’s going to turn out. I then take that spirit to the original work, and from there back to printmaking. It’s a constant back and forth.

And in the end, it’s a very Bauhaus way, isn’t it? To unite the major and minor arts, the popular, the applied… I’m interested in everything, and I don’t mind mixing it. But it’s true that the art market is very rigid about this: they prefer you to be clear and repeat what already works. Why? Because they don’t want risks. If something sells, it’s better for you to keep doing exactly that.

But of course, we go back to the beginning. The series, the works, end when you yourself say: “I’m getting bored, I’m repeating myself.” Then you need to change. Sometimes the series last, but they transform. Maybe it’s not noticeable if you only see one piece, but if you see an entire exhibition, you perceive how it evolves, how something changes.

I move constantly; I just can’t avoid it. I like it. Although I didn’t start that way. When I was 20, 22, 25 years old, I worked more with painting. But it was when I discovered printmaking that I understood that it allowed me to investigate my own practice from another place. I found it very interesting. And from there, I started collaborating with engravers, working in workshops, creating community.

Learn more about Regina Giménez on her Instagram and about here books here.