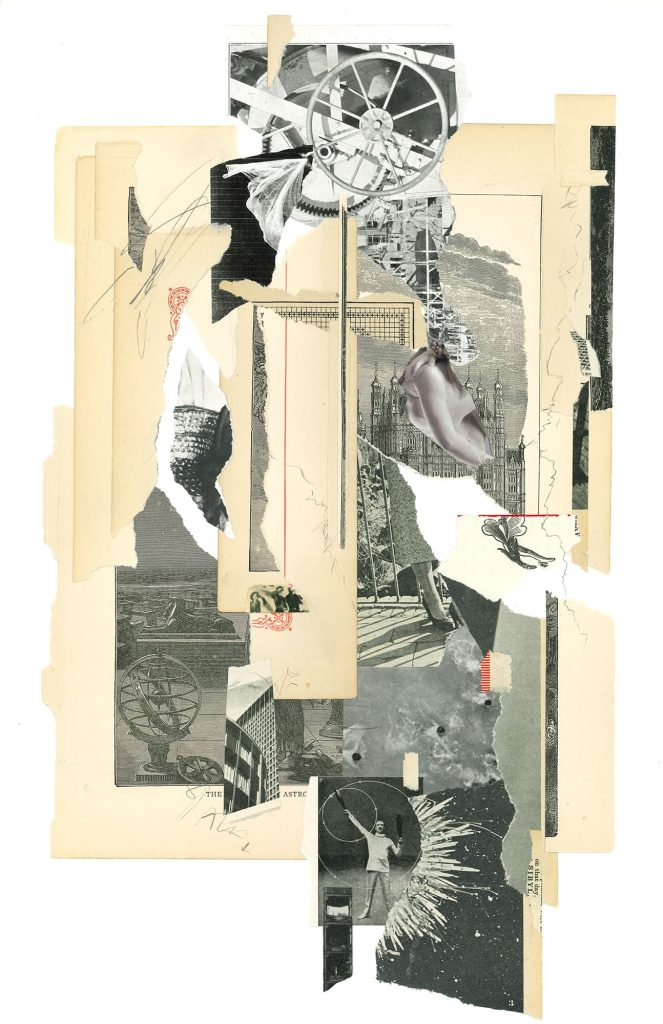

by Clive Knights.

Architect and collage maker Clive Knights doesn’t see collage as just cutting and pasting. For him, it’s how we make sense of the world—piecing together fragments, finding connections, building meaning from what’s broken or incomplete.

In “Fragmentary Gestures Towards the Invisible,” Knights draws on phenomenology (particularly Merleau-Ponty, Gadamer, and Ricoeur) to argue that collage has been unfairly dismissed as craft or “minor art.” Its accessibility—the fact that anyone can do it—is precisely its strength. Knights traces collage back centuries before Cubism, through domestic albums and pressed flowers, showing it as an ancient human impulse: to gather, arrange, remember.

What makes collage powerful, Knights suggests, is what it asks of us. The fragments don’t add up to neat meanings. They gesture toward something hidden, something that emerges only when maker and viewer both lean in, willing to play, to imagine, to participate in the work’s unfolding.

This is Part 1 of a two-part essay.

PART 1: WHY COLLAGEMATTERS TO A CULTURE

“…we situate ourselves in ourselves and in the things, in ourselves and in the other, at the point where, by a sort ofchiasm, we become the others and we become world.” (Merleau-Ponty 160)

The French hermeneutic philosopher Paul Ricoeur used to ask his students an initial question – “From where do you speak?” Not, who are you that is speaking, implying a sovereign identity that is yours and yours alone; but, where are you when you speak? In other words, the question acknowledges that one’s identity is not, perhaps, discrete and isolated like an island, but rather an amalgam of qualities formed in and through renewed acts of speaking from a shared cultural place. This implies that your sense of self emerges as an interpretation of multiple fragments constituted by the cultural milieu in which you actively participate with your body in its deployment of commonly understood actions, gestures, words, symbols and practices. The suggestion is that individual identity is articulated less by an inward submersion towards a center of pure and unadulterated selfness to be venerated in its uniquity, than it is by an outward excursion across the worldly terrain of human actions and settings that weave a matrix mapped in the configurations of language.

Humans are both linguistic and contextual beings who draw meaning from the figuration of relationships with all that lies both within, and beyond, reach. The cognitive scientist Mark Johnson states, “Human meaning concerns the character and significance of a person’s interactions with their environment. The meaning of a specific aspect or dimension of some ongoing experience is that aspect’s connections to other parts of past, present, or future (possible) experiences. Meaning is relational. It is about how one thing relates to or connects with other things” (Johnson 10). Art making is a primordial response to the human predicament of being in the world, and reflecting upon the practice of art is a dangerous task. The discursive precision of the written word in attempting to clearly present conceptual thinking about the human creative act can kill the very object of its investigation stone dead, like the entomologist’s collection of insects pinned down in taxonomic categories. I am not an art historian and I do not presume to comprehend art in terms of historical alignments, movements or legacies. Nevertheless, as a creative human being I have developed a deep passion for investigating what human creativity is all about, mainly so I can learn how to do it better myself, and be able to teach others. My guides have been many and varied, but include Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of the body, and the philosophy of interpretation (hermeneutics) espoused by Gadamer and Ricoeur. From these philosophers I discovered the roots of human communication in mimetic bodily gesture, and Aristotle’s notion of ‘poiesis’ – poetic making – where metaphor, the revelation of likeness, is the primary motivating force of creative activity, and, in fact, the guarantee of human community in how it reveals similarity in things that, on their face, differ. All forms of language are metaphoric both in origin and at their vital contemporary edge, at their creative horizon where new ideas emerge to challenge and enrich the familiar. As Philip Wheelwright has noted in Metaphor and Reality, “Poetic language, generally, by reason of its openness, tends towards semantic plenitude rather than toward a cautious semantic economy. The power of speaking by indirection and by evoking larger, more universal meanings than the same utterance taken in its literal sense would warrant, is one species of semantic plenitude. But it may also be that the tenor of an image or of a surface statement is not single; the semantic arrow may point in more than one direction.” (Wheelwright 57)

I am fascinated by how the notion of semantic plentitude, or as Ricoeur calls it, “a surplus of meaning” (Ricoeur 45), plays out through the contributions that all the poetic arts make to the settings of our lives. I speak as a collage maker but also as an architect, as one who configures the lived world with, and on behalf of, others. Architecture, of course, is always in the public domain and thus, potentially at least, has the upper hand over the other arts in communicating directly with its public as it aims to enrich and transform their lives with innovations of meaning. More recently though, unfortunately, architecture has, for the most part, forgotten how to engage this potential, but that is the subject for another discussion.

So often, the invention of collage is credited to the Cubists of the early 20th century. They championed the genre as a means of challenging the tyranny of perspective vision that has dominated painting and, indeed, architecture since the Renaissance. The Cubists attempted to paint the fullness of their experience of things in the life settings in which they unfolded over time. By refusing the unity of the singular fixed view, they were not breaking things up into pieces, they were actually more effectively visualizing the dynamics of their conversation with things installed in a shared lifeworld, ongoing, temporal and vital, rather than as ‘nature morte’, dead nature, the literal translation of the French term for ‘still-life,’ where autonomous objects languish in discrete arrangements across the deadening space of perspective vision. By contrast, the Cubists’ collages are ‘situational’, and as such, I would argue, they are architectural in how they engage the depth of life situations, not narrow perspectival depth, but ontological depth, the depth of being over and beyond the depth of vision, where vision is just one of the many dimensions of the fullness of being. The content of their collages remains alive, animated by our imaginative occupation of the spatial interstices and temporal intervals they evoke and that we recognize as fragments of our own life situations at the same time as we acknowledge the inexhaustible nature of the reality they infer.

A recent exhibition at the National Galleries of Scotland, titled ‘Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage,’ claimed that the origins of collage extend back as far as, perhaps, the invention of paper in China in the first century AD. The earliest work they gathered for this exhibition was from fifteenth century Germany (Elliott 10). The curators also recognized the burgeoning of domestic craft activity practiced predominantly by women in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Pressing dried flowers, for instance, pasting small watercolors of flowers into books, collecting paper memorabilia to paste into sentimental albums and so on, eventually augmented by the proliferation of images enabled by the invention of photography. These acts of gathering, collecting, and organizing betray the historical emergence of the collaging sensibility in the figuration of an array of fragments as an allusion towards a fulfilled life. They act as mnemonic devices, a mode of visual recollection, a refiguration of human relationships organized by the perspective of the one who remembers through the very act of making. In the ubiquitous, chronological photo- album that later ensued, the simplistic structure of temporal sequence replaced the more creative, figural act of the maker, nowadays entirely eclipsed by the disengaged, immaterial, algorithmic order of digital photo libraries.

In 1930, the surrealist poet Louis Aragon reflected on the virtues of collage over that of painting in an essay titled ’The Challenge to Painting’ in which he admonishes painters for being obsessed with self-expression and states that with collage “art has truly ceased to be individual” (Aragon 60). Elsewhere in the essay he says “Collage is poor. For a long time to come its value will be denied. It appears to be freely reproducible. Everyone believes they can make their own” (Aragon 61). I consider the accessibility of collage to those who remain uninitiated in the traditional skills of so-called professional art-making, or nowadays the sophisticated skills of digital visualization, to be a virtue. To the art world, it is seen as a reason not to take collage seriously. Yet, I see a collage as Octavio Paz sees a poem, “A magnetic object, a secret meeting place of many opposing forces” (Paz 14). A collage holds the promise of revealing something of that secrecy, like a divination of that which remains hidden despite all that the artist puts in front of themself in making the collage, and in front of others as they experience collage work, as they respond to these fragmentary gestures towards the invisible. I do not purport to have a theory of collage. Rather, in the manner of collage itself, I offer a gathering of fragmentary insights into collage and collage making in the hope that the light projecting from each might intersect enough to conjure the specter of coherent understanding, albeit temporary, partial and fleeting.

The architectural theorist, Dalibor Vesely, in his book Architecture In the Age of Divided Representation, references what he calls the ”restorative role of the fragment” in creative practice (Vesely 343). The apparent fragmentation of the contemporary world, he suggests, is manifest as so many isolated forms of specialist knowledge dislocated from a common, latent background, what he calls the primary or natural reality. The necessity in scientific research, for instance, to control the process of experimentation, observation, and verification, requires the encircling of its content to remove it from a broader lived reality into the controlled environment of the laboratory. The result is the conception of a positivist world built from separate, empirically clarified components joined by explicit logic. This is not the world of lived experience in which our bodies precede our thinking selves, and where we piece together partial perceptions bound by shifting, overlapping horizons, that imply a primordial whole without ever offering it up in its totality. These partial perceptions are a different kind of fragment with a synecdochical capacity to imply the fully present but never fully disclosed whole, a shared cosmos which surpasses each individual human life while informing and structuring the possibilities of each.

Linda Nochlin, in her book The Body in Pieces, identifies 18th century revolutionary dismemberment as an emblem of transformation and release from the dictates of monarchical and therefore religious hegemony (Nochlin 10), a symbolic ‘breaking apart’ that has its origins in earlier forms of iconoclasm; shattering a cultural whole into fragments, out of the debris of which the possibility of a new and differently comprised unity might arise. A fragment can be seen as evidence of a previous, complete thing now broken into pieces, a fragment ‘on its way from,’ so to speak. Alternatively, a fragment can be understood as a part of something incomplete, yet to be completed, a fragment ‘on its way to.’ The deftness of the collagist is to be able to enact the transformation of the fragment in either direction. The dismantling of books and magazines, of previous wholes issued by the machinations of popular culture can be seen, perhaps, as a form of contemporary iconoclasm, challenging preset meanings embedded in the iconography of printed media. The acts of cutting, ripping, tearing, splicing, displacing, removing, and re-assembling are minor revolutionary acts in themselves, performed within the reach of the hands and the purview of the eye. But then, like the quarry of archeologists, these multiple fragments of previously manufactured artifacts, once released from the fixity of the medium in which they have been buried, hold the potential to speak of imagined worlds, re-enacted in terms of human lives and their unfolding.

In his insightful essay “On the Relevance of the Beautiful,” Gadamer identifies ‘play’ as one of three crucial aspects of meaningful art (Gadamer 22). To play at ‘make-believe’ as a child is the burgeoning stage of mimetic creation, to imagine ‘as if ’ something, a blanket stretched between two chairs, is something else, a castle, yet without the configuration ever literally becoming a castle or ceasing to be a blanket and chairs. If any meaning is to be gleaned from this playful event by its creators or its spectators, it derives from the shared willingness of all to participate in a metaphoric shift, to recognize something as something else and in so doing to commune in being re-oriented together. As Gadamer reminds us, “Something known assomething means: to know again, but recognition is not merely a second re-knowing after a first acquaintance. It is something qualitatively different. When something is recognized it has already been liberated from the uniqueness and accidental elements of the circumstances in which it is met. It begins therein to raise itself to its perduring essence and to become unraveled from the accidental character of its occurrence. (my emphasis, quoted in Schweiker 59)

A collage is the site and outcome of playful, mimetic incarnation, where it is the artist’s developing relationship with the fragments and the worlds they invoke, that is presented, the result of which cannot be pre-ordained. If a collage can carry any meaning at all it is ‘bodied-forth’ in the only way available to the work itself, and there it awaits interpretation by the viewer. A collage demands effort on the part of viewers to be willing to participate themselves, engage their imagination, seek out the situational meaning of the combination of fragments, “in the context of the world to which each fragment directly or indirectly refers” (Vesely 337). Do not expect to be fed neatly pre-packaged unambiguous, and explicit significations. That is not how participation works, it demands give and take, openness and offering, attention and response. It takes sincere imaginative effort to recognize the blanket and chairs as a castle, just as it did for ancient cultures to see the city as the cosmos, or a lump of stone as an ancestor. Stated another way, in the collage-making act, the material fragments and the collage maker collaborate in a search for an elusive, hidden, but ever-present otherness, where the combination of fragments reaches beyond what each literally is. The resultant collage acts as a cipher between the viewer and that otherness, to be recreated through open, participatory, and above all, imaginative involvement. In this way, collage challenges vision to look beyond itself, beyond visual perspective and objective thinking, deep into the communicative space of the collage where the fragments metaphorically engage with one another and thus go beyond themselves to reference not only the multiple contexts from which they are sourced (fragments withdrawing from a whole), but also a world of nascent and unexpected liaisons (fragments opening onto a whole). As Vesely says, “Meaning depends on the continuity of communicative movement between individual elements, and on their relation (reference) to the pre-existing latent world” (Vesely 345) to which they all, together with the collage maker and the collage viewer, belong, a world “always present, waiting for articulation” (Vesely 338).

Part 2 of this essay will look and what collage can be by way of analogy to conversation, to the poem, to theatre and to song. A version of the full essay first appeared in both English and Italian in Visione ed Intuizione, la Ragione dell’Arte (“Vision and Intuition, the Reason for Art”), edited by Roberta Guarna, Italian Collagists Collective, Bari, 2021.

Learn more about Clive Knights on his website or Instagram

Bibliography

– Aragon, Louis, “The Challenge to Painting” TheSurrealistsLookatArt,edited by Pontus Hulten, Lapis Press, 1990, pp.47-74

– Brook, Peter. TheEmptySpace.Simon & Schuster, 1968

– Eliot, T S. FourQuartets.HBJ Books, 1943

– Elliott, Patrick. “Collage Over the Centuries” Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage,National Galleries of Scotland, 2019, pp.9-23

– Flusser, Vilém. Gestures.U Minnesota Press, 2014

– Gadamer, Hans Georg. TheRelevanceoftheBeautifulandOtherEssays, Cambridge UP, 1986

– Ingold, Tim. BeingAlive.Routledge, 2011

– Johnson, Mark. TheMeaningoftheBody.U Chicago Press, 2007

– Kearney, Richard. Touch.Columbia UP, 2021

– Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. TheVisibleandtheInvisible.Northwestern UP, 1968

– Nochlin, Linda. TheBodyinPieces.Thames & Hudson, 1994

– Paterson, Don. ThePoem. Faber & Faber, 2018

– Paz, Octavio. TheBowandtheLyre. U Texas Press, 1987

– Ricoeur, Paul. InterpretationTheory. Texas Christian UP, 1976

– Schweiker, William. MimeticReflections.Fordham UP, 1990

– Vesely, Dalibor. ArchitectureintheAgeofDividedRepresentation. MIT, 2004

– Wheelwright, Philip. MetaphorandReality.Indiana UP, 1962