All photos by Todd Bartel.

In March of 2022, collage-based artist Todd Bartel visited the studio of little-known collage and assemblage artist Salvatore Meo (Italian, b. Philadelphia 1914–2004 d. Rome). Mary Angela Schroth, the Artistic Director of Sala 1—Italy’s oldest non-profit art space—and the founder and President of the Fondazione Salvatore Meo, invited Bartel to develop a project to pair and exhibit his work with Meo’s. After a year of preparation and a three-week residency with the Fondazione Salvatore Meo from late November to mid-December 2023, the project culminated with the exhibition entitled As Is at Sala 1 in March of 2024. This was Todd’s second residency in 2023, during which he produced a focused body of work that shed light on the two artist’s various approaches to collage and assemblage. The work he created for the As Is show overlapped in concept with his work at his Weir Farm residency in July, the summer before. (To read the first interview, follow this link: Reflections on Nature—Todd Bartel’s Artist Residency at Weir Farm.) The As Is exhibition ran concurrently with his Landscape Vernacular exhibition at Anna Maria College, Paxton, MA. In this follow-up interview, we discussed Todd’s residency at Fondazione Salvatore Meo and how he continued his work on the theme of “nature” while working in Rome.

AB –You share a mutual affinity for materials and a dedication to collage and assemblage with Salvatore Meo, the artist for whom this residency was centered. Tell us a little about the Foundation and how you became involved.

TB –I felt an immediate sense of resonance with Salvatore Meo’s found materials approach to collage and assemblage during a slide lecture that introduced me to his work, given by curator Kelli Bodle (Boca Raton Museum of Art, Boca Raton, FL) in November of 2021. During her talk, Bodle shared that it was possible to visit Salvatore Meo’s studio. Afterward, I wrote to Mary Angela Schroth about visiting Meo’s studio during a trip I had already planned for March of the coming year. Her answer came as a surprise. She followed my website address in my email signature without provocation, and when she replied to my visitation inquiry, she said, “Love your work, and feel that perhaps we could even do some kind of project with you in the Meo studio in Rome…So for sure, let’s meet up in Rome.” I feel quite fortunate and grateful for Mary Angela’s unsolicited acknowledgment of the shared affinities between my work and Meo’s and it was a thorough joy to collect monographs on his work and to learn about his approach to artmaking. After my first visit in 2022, we began planning a project in earnest.

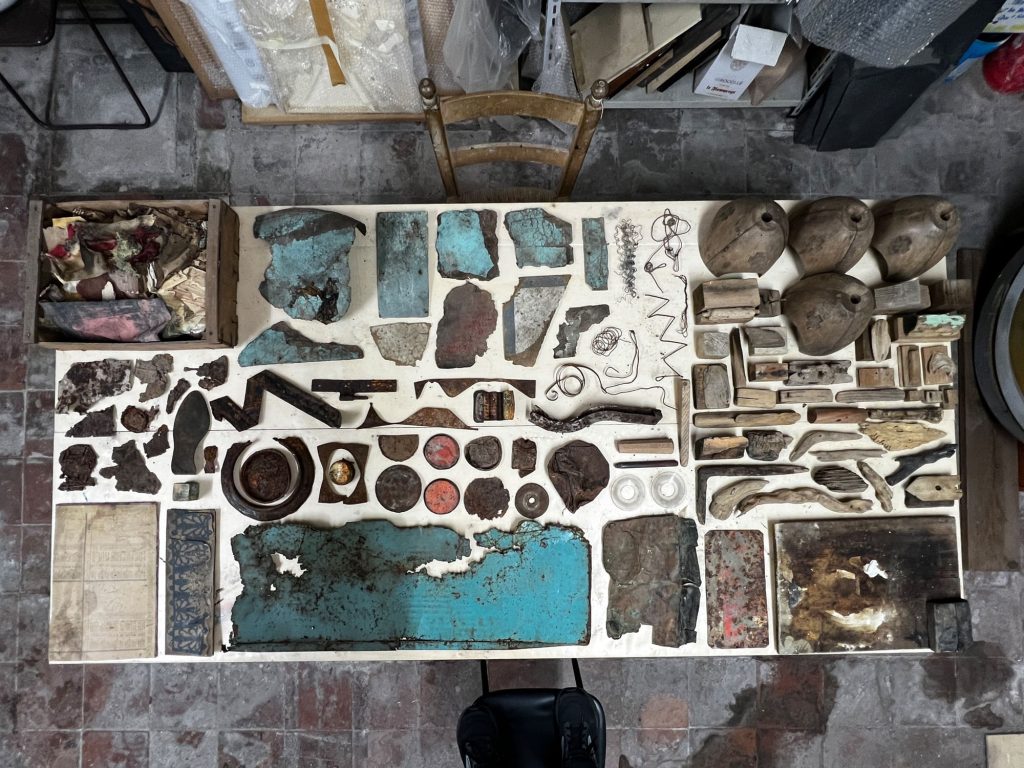

While I was invited to plan a residency at the Fondazione Salvatore Meo, there is yet no formal residency program; the foundation is in its early years, and programming is a bit impromptu. I am the second artist invited to plan a project with the Fondazione Salvatore Meo. The site itself is Meo’s studio, which is now a protected landmark in Rome. It is, for the most part, as he left it after his passing in 2004. It is quite literally a time machine that allows visitors to see how the artist worked. The time embedded in the things Meo collected remains visible in the fabric of the place. For example, in the initial photograph of the second floor, the arrangement of objects is actually an installation piece titled My Life that the Foundation is working to restore. The present state allows you to see that he kept things on the wall for very long periods, as evidenced by the ghosted shapes of objects that have been removed. That kind of time is felt throughout the place. Meo came to Rome in 1949 and while it is not the studio that Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly visited him in 1951, he occupied the Foundation studio just a few years later. Many of the works of art scattered about the Foundation Studio trace the span of time he worked in Rome. The things he collected and distributed about the place capture the feeling of the nearly six decades he worked in Rome. It is an incredibly rare window into an artist’s creative environment.

Since there are no accommodations for visiting artists at the Meo Foundation, my actual residency was divided between several locations. I rented an apartment in Trastevere, strategically located between the three places I needed to frequent during my time in Rome: the Fondazione Salvatore Meo, Cosetta Mastragostino’s studio, and Sala 1. I did my collage work at the Trastevere apartment, produced assemblage work at Cosetta’s studio, and regularly visited Meo’s studio to do research. I was even invited to spend time in his attic, where boxes and bags of materials he collected that never made it into his work still reside. Moreover, I was invited to select materials to work with — that had been designated for the trash.

AB –This wasn’t your first time living and working in Rome. You studied in Rome between 1984-85 as a European Honors student in painting during your senior year at Rhode Island School of Design. What was it like to live and work in the Eternal City as a seasoned artist? Knowing you had to downsize to work in Italy, please describe your studio setup in Rome and how you managed the needs of a studio practice abroad.

TB –One never grows tired of Rome! I can still manage to speak Italian, and I quickly get around because I still remember where to find everything, and so, in many ways, it felt like a homecoming. Of course, there are inexhaustible treasures to see, but I elected to be particularly focused during this residency to develop an entirely new body of work during my sojourn. In the mid-1980s, I was developing my voice as a collage artist. I was slow to create work back then and was often inefficient with my time, whereas my focus and intentionality were much more honed this time around, 40 years later. Interestingly, the way I collect materials was exactly the same then and now—eyes always looking at my feet, ready to find and ever-ready to visit flea markets, book shops, and antique dealers.

While I knew what I wanted to do for the Meo Residency, generally speaking—to address themes that address landscape and nature—I had to produce a lot of work quickly. Out of respect and interest for my environs, I elected to limit myself to working with materials obtained exclusively while in Rome.

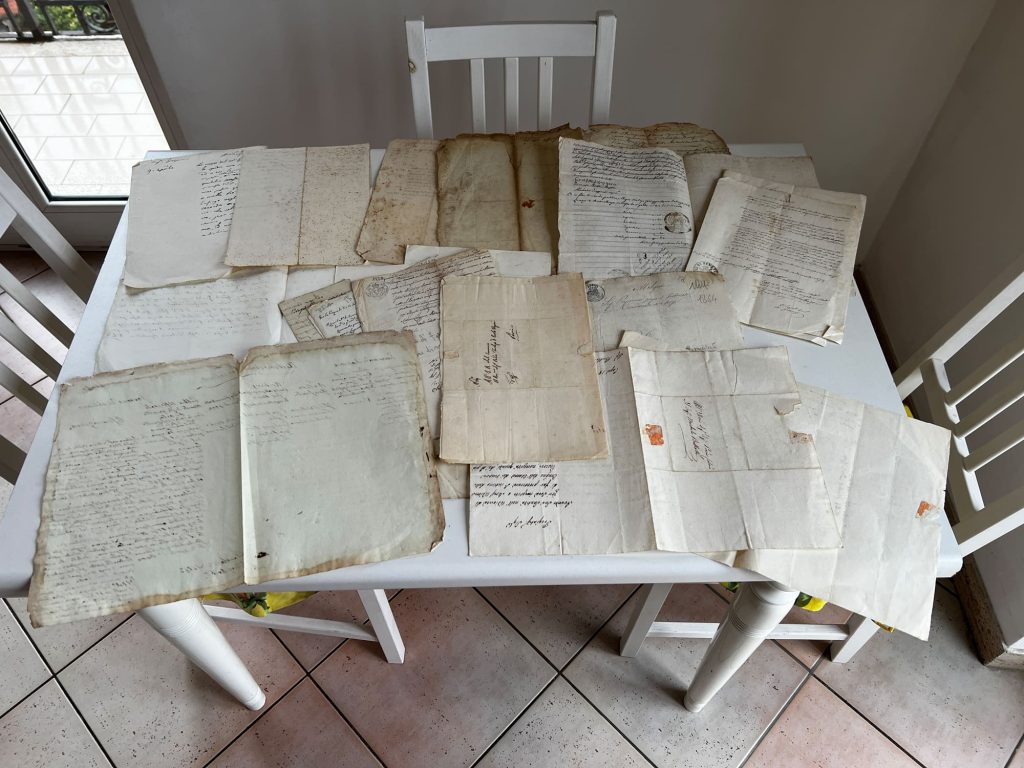

That prospect was as daunting as much as it was exhilarating. For starters, I brought some of the original materials I had found in Rome in 1984-85 with me to the Meo residency. I also procured materials at antique bookshops and the well-known Sunday flea market at Porta Portese. But much of what I used came from discarded materials I found along my walks. During my three-week stay, I visited Porta Portese twice, where I obtained many of the object-based materials that I ultimately worked with. I made a habit of visiting the open-air market twice each time I went. I went in the morning, just after they opened—along with every other antiquer—and then later in the day after the vendors left. The wake of the market is where I found half of the materials I used discarded on the streets of Rome—mostly paper-based but also sculptural.

I brought materials with me to ensure I would not be at the mercy of what I could newly find, but I really wanted my inspiration to emanate from what I found while I was in Rome. That’s a bit of a challenge because it is risky to depend on what you don’t have in hand when time is short in supply. I lucked out and found all my materials by the end of my first week. I worked intensely afterward and developed all the collages and all the assemblages in the remaining two weeks.

Regarding my workspaces, I was offered a place to use tools so that I did not have to bring them with me to Italy. Mary Angela’s long-time artist friend, Cosetta Mastragostino, was very kind and generous in lending her studio and tools since she was not planning to work in her studio when I was scheduled to be in Rome. Without her space, I would have been hard-pressed to make the assemblages.

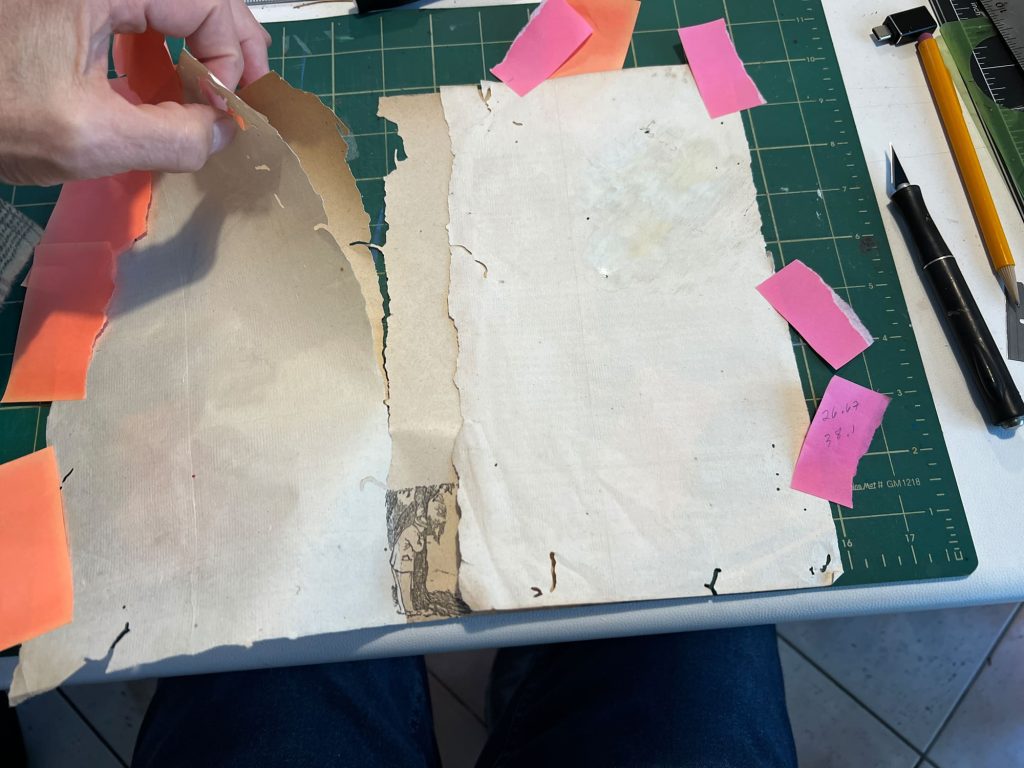

Cosetta’s basement studio proved to be a bit too dark a workplace for the intricate cutting I employ when making my interlocking collages, so I used my apartment’s kitchen, which is a glorious, light-filled space during the day.

Simultaneous cutting allows for identically cut shapes to be exchanged, which results in the creation of positive/negative interlocking collages.

Joining “trace-cut” 19th-century end pages to form the semblance of a tree in the space between the pages using a darker-toned, 20th-century end page in the middle

AB –How does the phrase “as is” capture the essence of your individual creative processes? In what ways do the As Is collages reflect the shared interests and aesthetics between you and Salvatore Meo?

TB –Rome itself sheds a lot of light on my answer. Meo lived in Rome beginning in 1949, and I lived in Rome between the school year 1984 – 85. We never met while we both lived in Rome at the same time, but our respective neighborhoods bordered one another, and no doubt our mutual creative interests could easily have made our paths cross—I often wonder if they ever did.

Regarding a kinship with materials and our respective interest in collage and assemblage, we share an obvious affinity for aged things—Rome is filled with them, and the city itself visibly embodies the patina of history. We share classical and minimal sensibilities for arranging found materials, and such classicism and elegance abundantly surround everyone who walks the streets of Rome and visits its wonders. I’d point out, however, that in my estimation, despite the prominence of the collage aesthetic in the 1980s—and even now—it is not so common to find artists who are exclusively dedicated to collage practices. Sure, there were hundreds (likely thousands) of artists using collage within their practices, but it is something altogether different when an artist dedicates their creative oeuvre to the pursuit of what collage is and what collage can be. Meo and I share that commonality too. I like to muse that if we ever walked down the same street simultaneously, we would most certainly have fought over picking up the same city detritus.

While I was in Rome as an emerging artist in the mid-80s, I had not yet dedicated myself to understanding the history of landscape; I tended to make art about whatever was suggested by the things I found. In this way, my older work, like Meo’s work in general, had a kind of unwieldy randomness that was unified by a sense of visual poetry of the random things we found. Interestingly enough, when I studied in Rome, I used to repeat to myself the phrase “painting as poetry” over and over in my mind. For me, visual poetry was a kind of joiner of aleatoric happenstance visible in aged materials. As an aesthetic, it was the city itself that cemented my interest in weathered surfaces. I not only collected worn materials there but also dedicated my studies to learning how to make them.

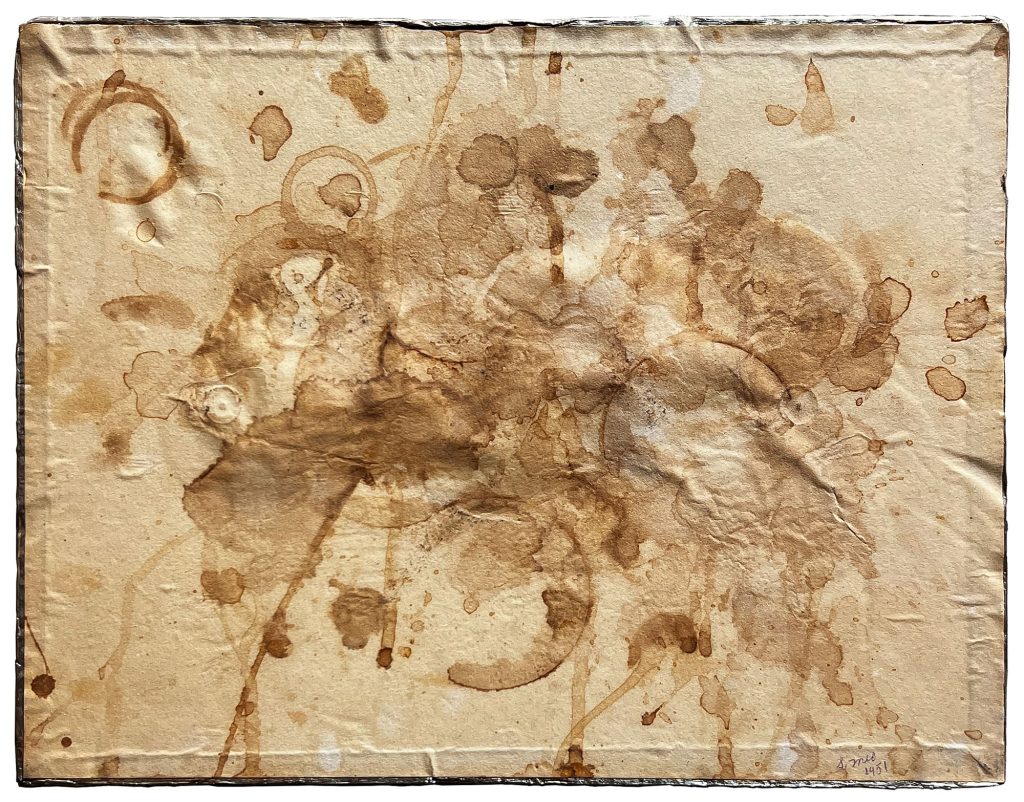

I sometimes had to apply a makeshift patina to age my materials because they were not weathered enough. Meo was similarly drawn to weathered materials, but Meo would never purchase his materials. He would collect the most decrepit items off the streets of Rome—what most people wouldn’t want to touch, let alone use. Furthermore, Meo frequently used these items without alteration other than what it took to fix them in place.

The first sense of “as-is” that both our respective practices share is that we both tend to have a high regard for things that reveal their history. But we, of course, diverge in our applications of using what we find. While we both gravitate toward the object trouvé and the strategies associated with using the readymade and the assisted readymade, Meo is more apt to place two things that generally point to meaning when placed near one another, whereas, in contrast, I tend to heighten meaning through juxtaposition in overtly conscious and often linguistic ways.

Another sense of As Is has to do with the potential of materials to suggest similes—two things of different kinds that link in a way, or a thing used as something else or otherwise representing something else. In this regard, both Meo and I tend to allude through our juxtapositions. However, in my case, it is the norm, and in Meo’s case, such communicative possibilities were less common. Most of Meo’s work was made with emotive- or visual-based poetics, not linguistic- or concept-based poetics. I had read a lot about Meo’s work between my first visit to his studio and my residency, and I recognized the simile concept early on, which inspired the show’s title.

AB –How did materials from the streets of Rome and from Salvatore Meo’s studio play a role in shaping the visual and conceptual elements of the As Is series? Was it meaningful to use materials from the artist’s own collection?

TB –I had no problem finding things I was attracted to of Meo’s to use. Everywhere I looked in Meo’s studio was of great interest! In some ways, I felt unsure of using someone else’s collected things. The documentarian in me wanted to leave everything as is—right where I found it. But it was not the first time I had been given materials that belonged to other artists. I often make work that pays homage to the artist whose materials I use or reference. It was easy to follow through with the invitation to use Meo’s unused attic holdings. What was hard was only taking what I could carry with me! There are six visible items on the tabletop photo in Cosetta’s studio that ultimately went into the assemblages I made, and I am sure I will use many more of his materials, which I will always credit in my material listings.

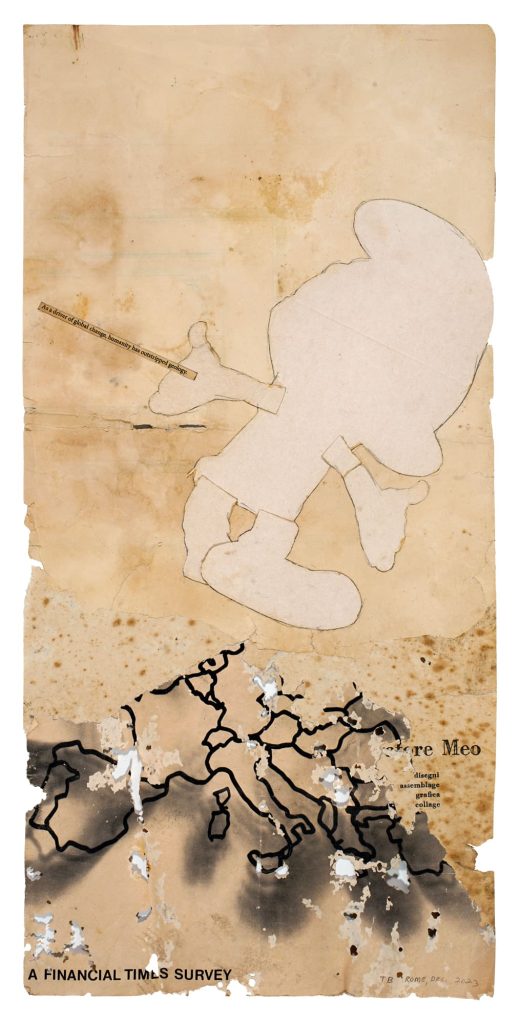

In one of the largest colleges, As Is [No. 8] (Driver), the bottom half is entirely made from Meo materials:

• a severely bug-eaten poster fragment with a generalized map of Europe, bearing the words “Financial Times Survey”

• torn pieces of vintage, foxed paper—upon which I transferred text from an exhibition announcement I found in his drawer that I brought to a photocopy store (Trastevere Stampa) and made several copies of.

The announcement disclosed the types of Meo’s work exhibited, the list of which I felt was a great way to catalog the various ways Meo worked with found materials. Also, Meo’s surname poetically points to or implicates a would-be viewer in a playful way as if to say, “It’s me.”

Interlocking collage, poster fragment collected by Salvatore Meo, Smurf print on cardboard and xerographic transfer on 20-century end-page cutting inset into Florentine book page (Book of Kings c. 1900), xerographic transfer on 20-century end-page cuttings, document repair tape. Text at upper left: Jedediah Purdy, After Nature, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2015, p. 1

“As a driver of global change, humanity has outstripped geology.”

Collection of Fondazione Salvatore Meo

The upper half of the collage was formed of things I found in Rome from both times I lived and worked there. I used the last piece of paper from a book I purchased in 1984—a book titled “Libro dei Re” (Book of Kings). Almost every collage I produced in Rome as a student there was made on pages from that book. I knew when I brought the last remaining page with me to the Meo residency that I wanted to use it somehow. I used the reverse side of a cardboard cutout of a Smurf as the primary image, which I found on the street during my first week in Rome in December.

The choice to use the Smurf was significant because it is VERY unlike the type of imagery I tend to work with. I allowed for the breach of personal aesthetics as a way to honor Meo’s sense of whimsy, which is prevalent not only in his work but evident in all the trinkets he littered throughout his studio. In one instance, he placed a saw on top of one of his assemblages as though it were an integral part of the work—visible in the stairwell photo at the top of the article. Toy figurines and fragments are regular additions in his assemblages and collages. What also interested me about the Smurf inclusion was the possibility of linking that character as a kind of court jester, which is not a far leap of the imagination to embed into a page from a Book of Kings. When I found it on the street, it was upside down and facing away from me; I recognized it instantly and thought, “I would normally walk right past that—but look at it! It aged well and has the neutral color of my Landscape Vernacular series.” I knew on the spot I would break my own rules to put it into a collage.