– Please, introduce yourself, tell us a little bit about you.

I live in Manchester and work at the University Centre at Blackburn College as Print Technician on the Visual Arts BA (hons) course. My practice is based in collage and screen print and I work mainly with archive images from local history collections.

I’m interested in architecture and urban planning and regeneration, particularly post war modernism and brutalism and the role these architectural styles played within social housing and the creating of new futures and building of new times.

This extends to research interests in the development of the Welfare State and the history of the Working Class movement, that further inform my work.

There’s also a huge element of the personal within my work, a passion for my Home Counties of the North West of England and my identity as a Northerner; investigating the landscapes, heritage and industry of the region.

– Your work seems to unite elements that are apparently very far away… How do post-industrial Salford and the female body gather in your work; and what are the issues you want to talk about through them?

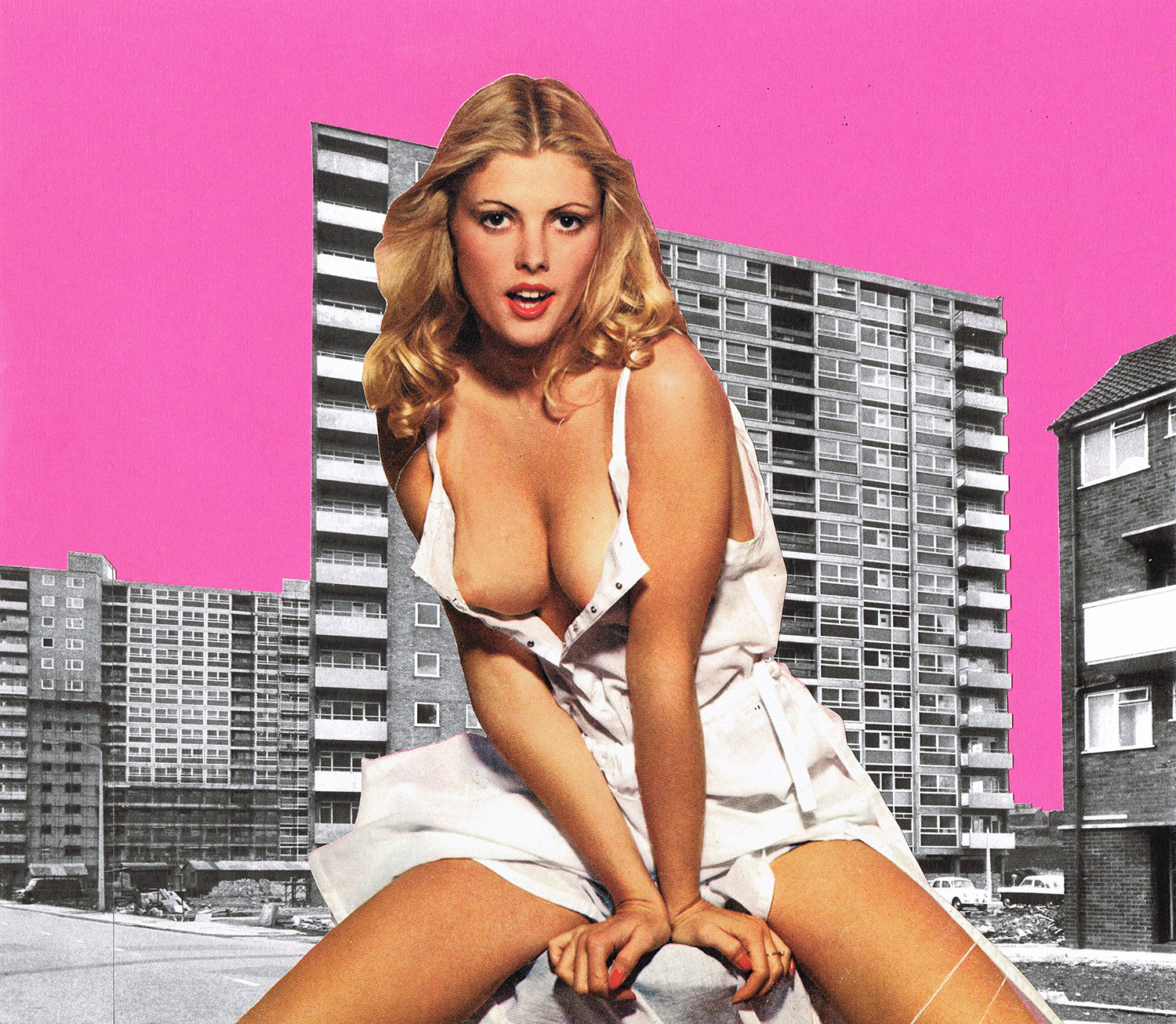

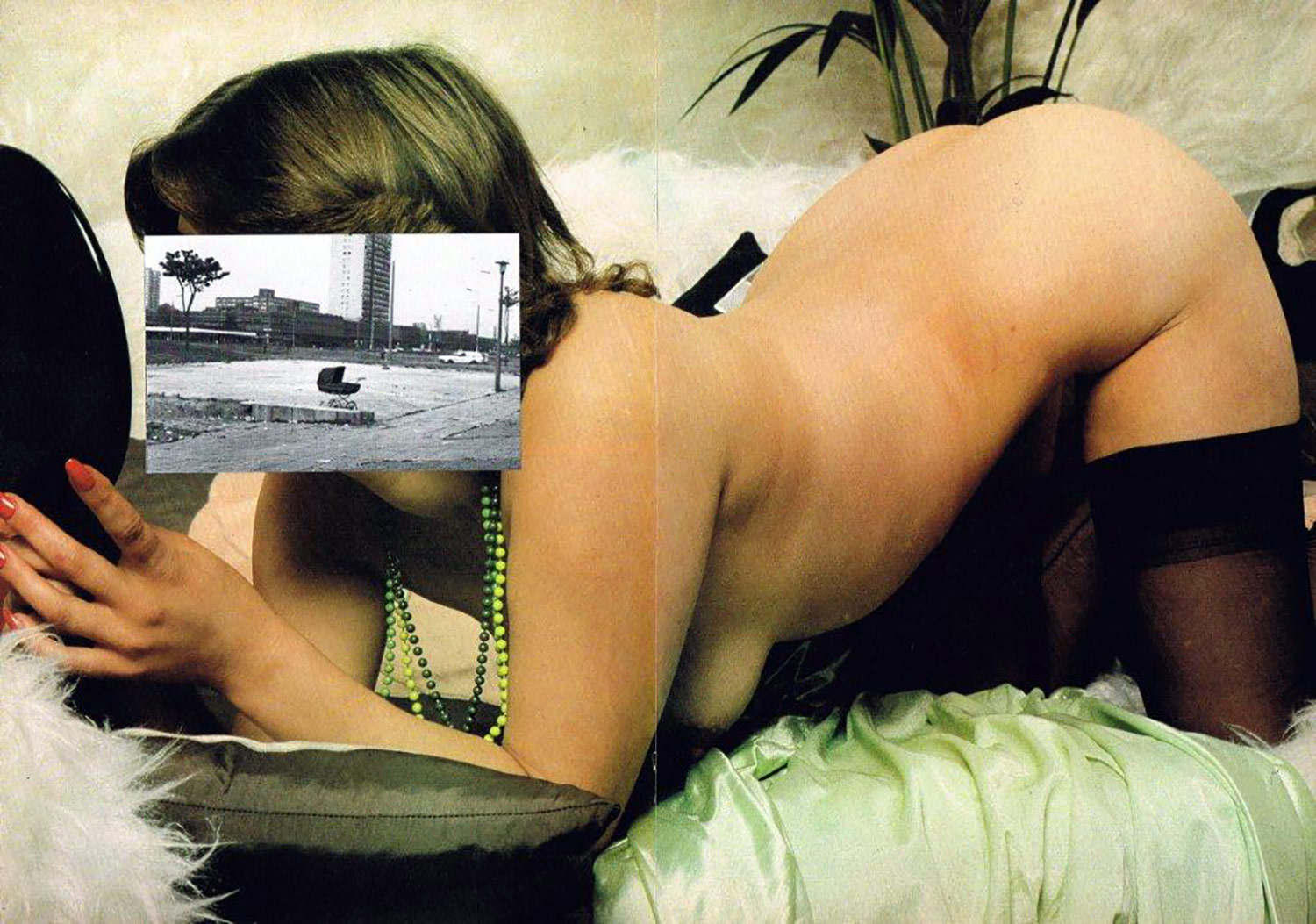

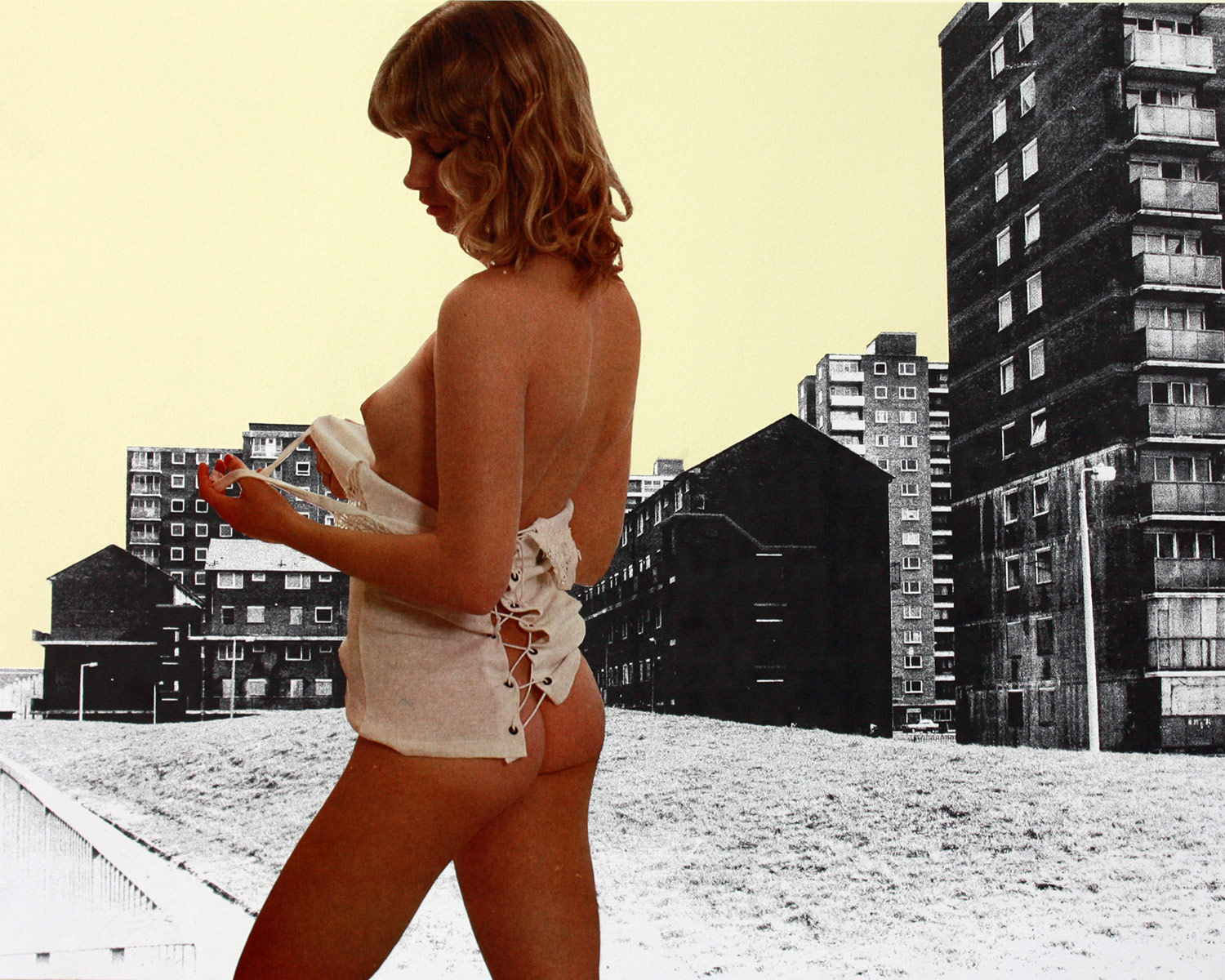

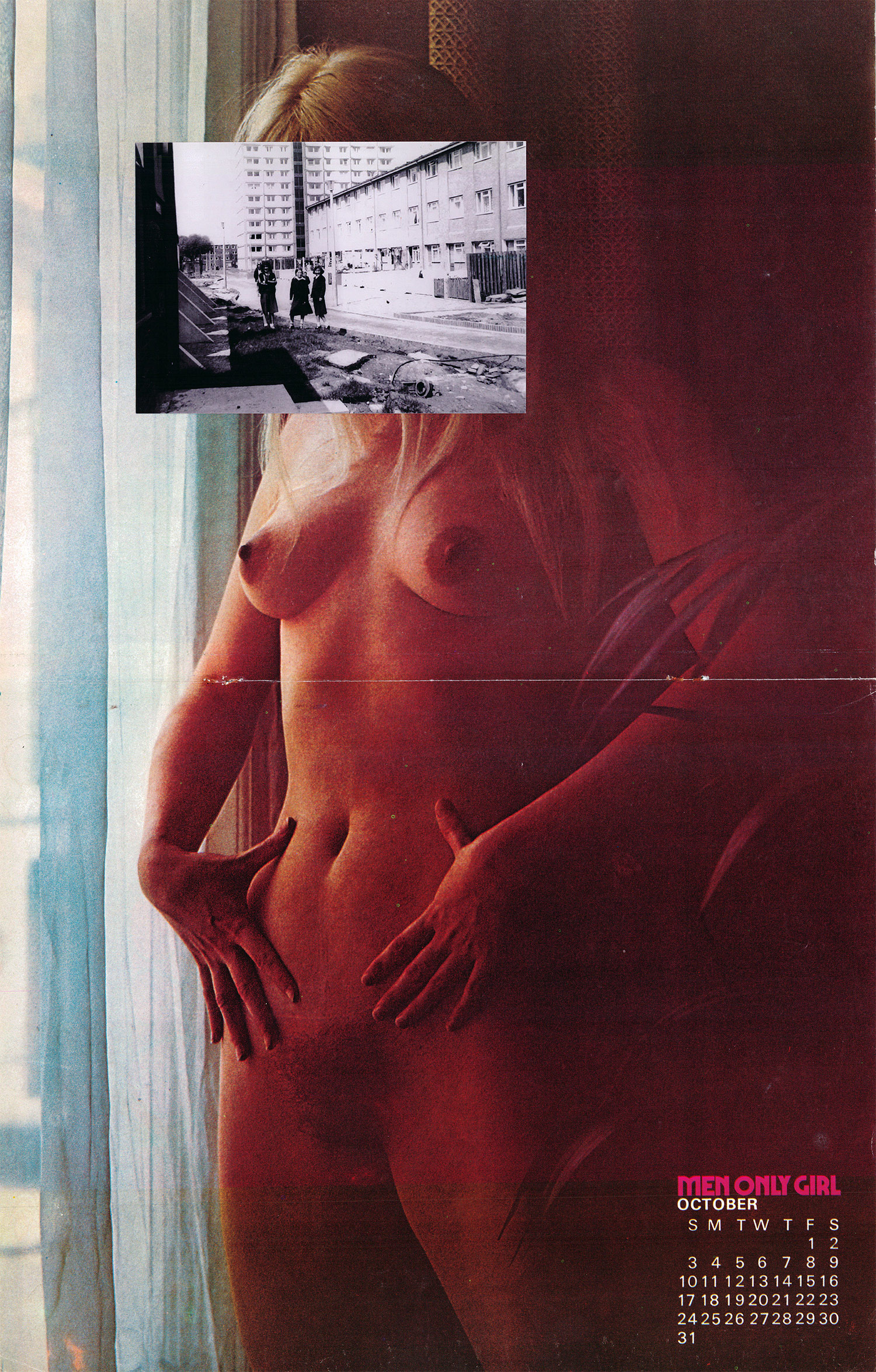

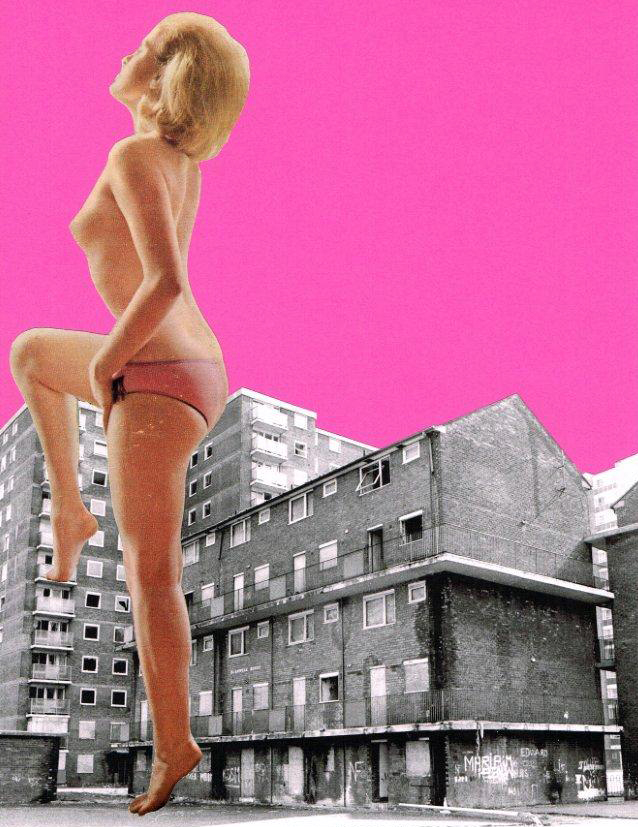

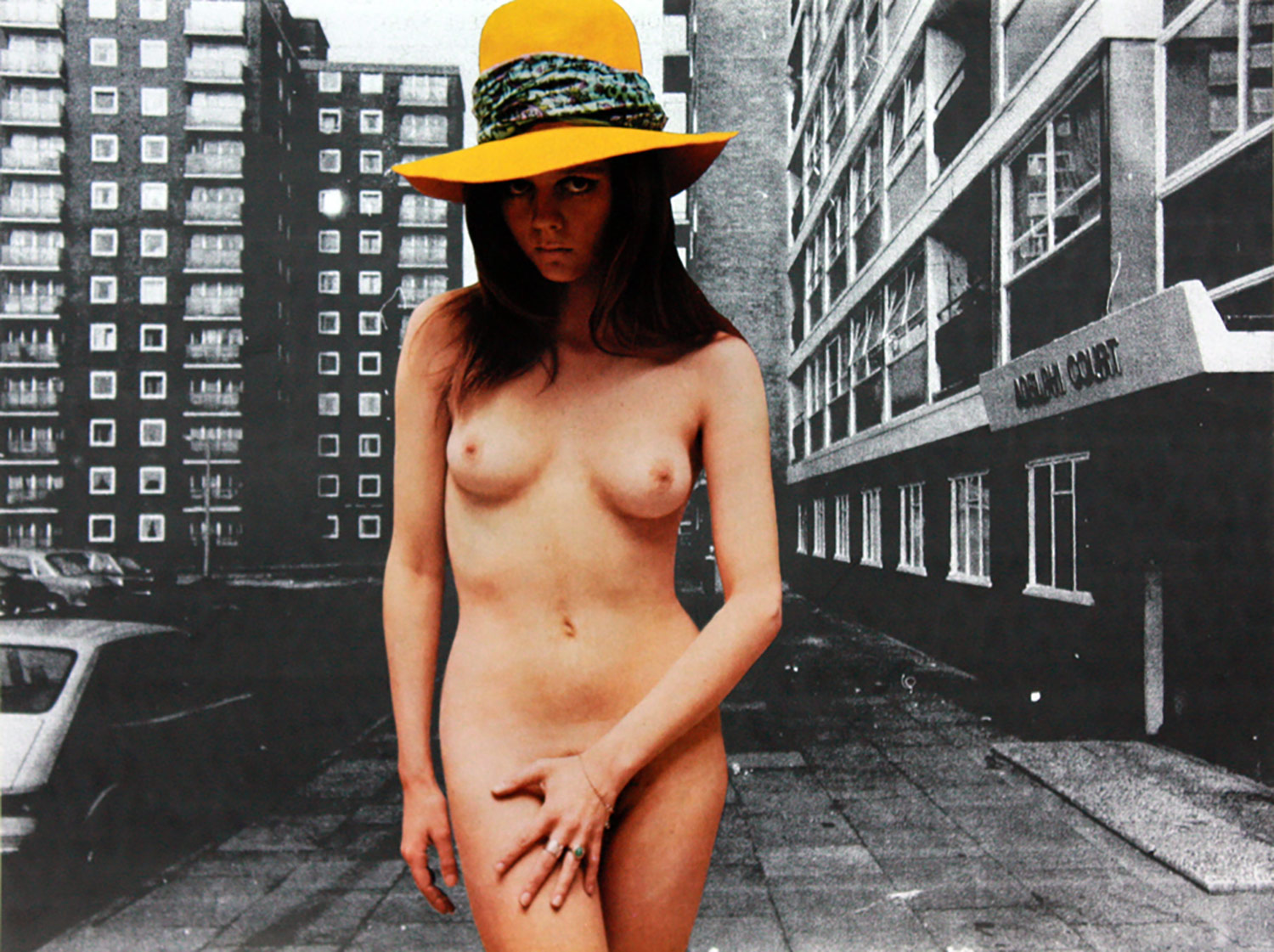

I work with images from public archives and images from vintage porn magazines, primarily from the same era; using images of women printed at roughly the same time as the tower blocks are documented being built.

So in some ways, there’s a unity of time within the juxtaposition of images.

There’s also an element of a personal and lived experience within the work, a kind of self portrait of my journeys through these post industrial landscapes, so this is perhaps where the female body gathers in these post industrial landscapes.

And while I’m not particularly trying to talk about anything through my work, I am however questioning gender roles, sexuality, cultural stereotypes and researching the influences architecture and political, social and housing/planning policy have had on dictating female identity within a particular regional setting.

In my work, the women are presented on a huge scale compared to the architecture, giving them power and prominence and turning the landscapes they inhabit into playgrounds; a bit reminiscent of the ‘Attack of the 50 Foot Woman’ 1958 film poster.

The women are in charge, in control and these housing schemes that are currently being re-developed, obliterated and gentrified are protected by these unmoveable matriarchal monoliths.

– What drew you to work with collage?

I get asked this question a lot and I honestly don’t know the answer!

It was a totally unconscious thing when it started but I guess it stems from my obsession with archives and print ephemera and my own ferocious need to collect images.

I’d been working more sculpturally with found objects while I was studying at the University of Salford and when I graduated in 2008 the process just morphed into a more two dimensional form with images instead of objects.

For me, collage provides a great vehicle to reveal hidden histories, uncover forgotten narratives and in many ways make the impossible real.

– How do you perceive the role collage in contemporary art?

With its roots in the photo montage tradition of European modernism, which was politically anti-fascist during a time of rising totalitarianism, I think collage now coincides with similar political shifts taking place across the world today and has the ability to be a tool to critique the status-quo.

The medium can cut and paste history and juxtapose epoch spanning imagery to question and challenge the contemporary issues we are struggling to resolve.

Now, more than ever, we need art to be political.