TWS –Hi Andrea, can you please tell us something about yourself?

AM –I’m a Canadian artist. I grew-up in Toronto, Ontario and have lived in the maritime town of Sackville, New Brunswick for most of my career. Sackville is a rural place with a disproportionally large artist community—mainly visual artists and musicians. Among other favourite things, it’s home to a summer music festival called Sappyfest and an artist-run centre with a great artist residency called Struts Gallery.

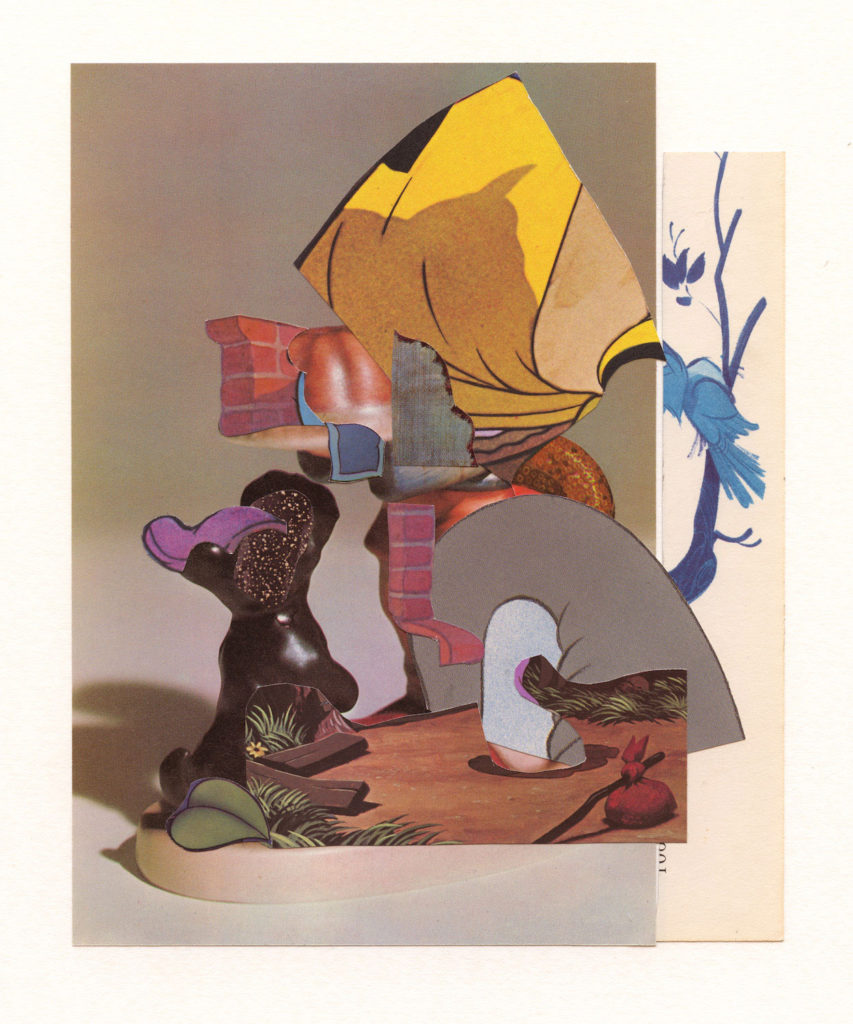

TWS –Andrea Mortson, collage artist, is the doppelgänger of Andrea Mortson, painter. Can you tell us about the difference between them? How did you get started and what led you to the other medium?

AM –I’ve spent the majority of my career working exclusively with oil paint on canvas. Being someone who has too many ideas, I sometimes set limits in my practice to avoid getting overwhelmed. Using only one medium was a way to do that. When I started collaging after a 20+ year painting career, it was intended to feed my paintings. I knew I didn’t want to paint from collages directly, but I thought I’d find other ways that collage could inform my practice.

Then, once I started collaging, I stopped painting. I realized that I was tired of seeing the world through the lens of painting… and more than this, through the lens of the history of painting… and even more than this, I was so, so tired of the blank canvas. It suddenly struck me as grotesquely disingenuous as a starting point.

So the collage artist has replaced the painter for now. There’s no difference between the two, other than the tools. I keep thinking that a return to painting is imminent, but for now I’m solely focused on collage. My studio space is a frightening mix of the two mediums—they are still very much in opposition to each other—but I haven’t ruled out the idea that they might one day meld. (Sounds so creepy.)

TWS –What do you find unique in each medium?

AM –When I’m painting it’s just me and the canvas, and the weight of hundreds of years of Western/Eurocentric perspective. It’s simultaneously lonely and oppressive. Every blank canvas is loaded. I find it strange then, that it’s the idea of the autonomous gesture that I miss most about painting despite believing it’s impossible. Or maybe it’s just the ability to make an exacting mark with one stroke that I miss.

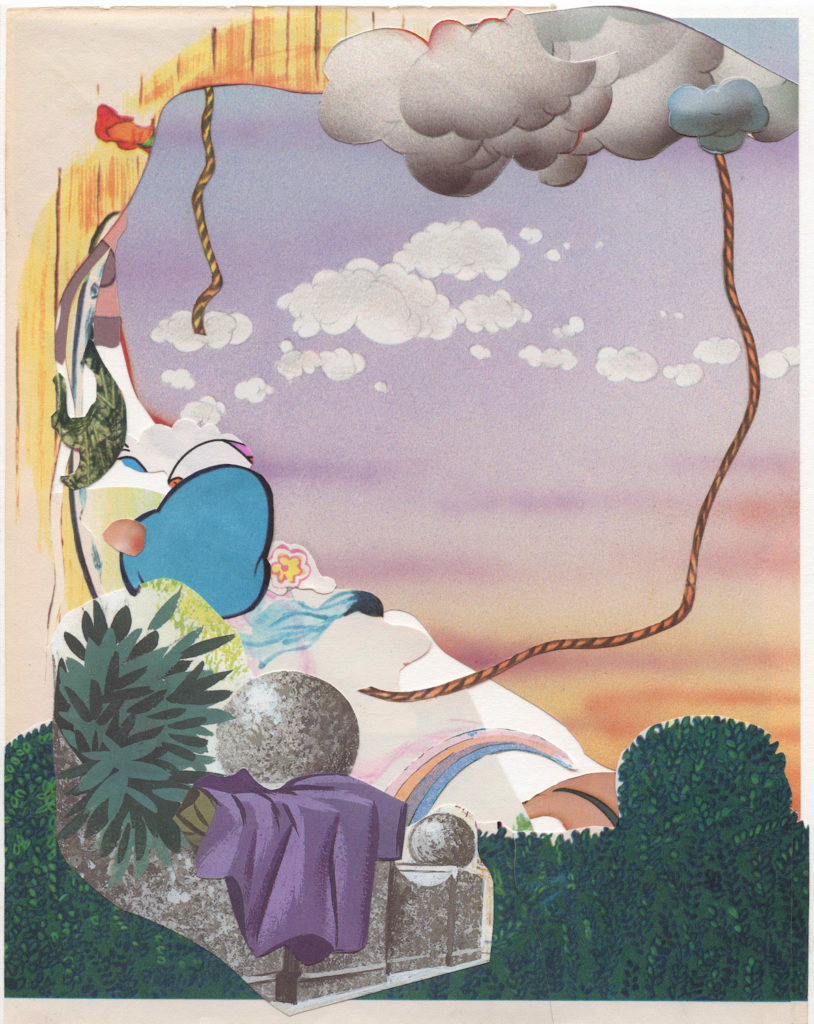

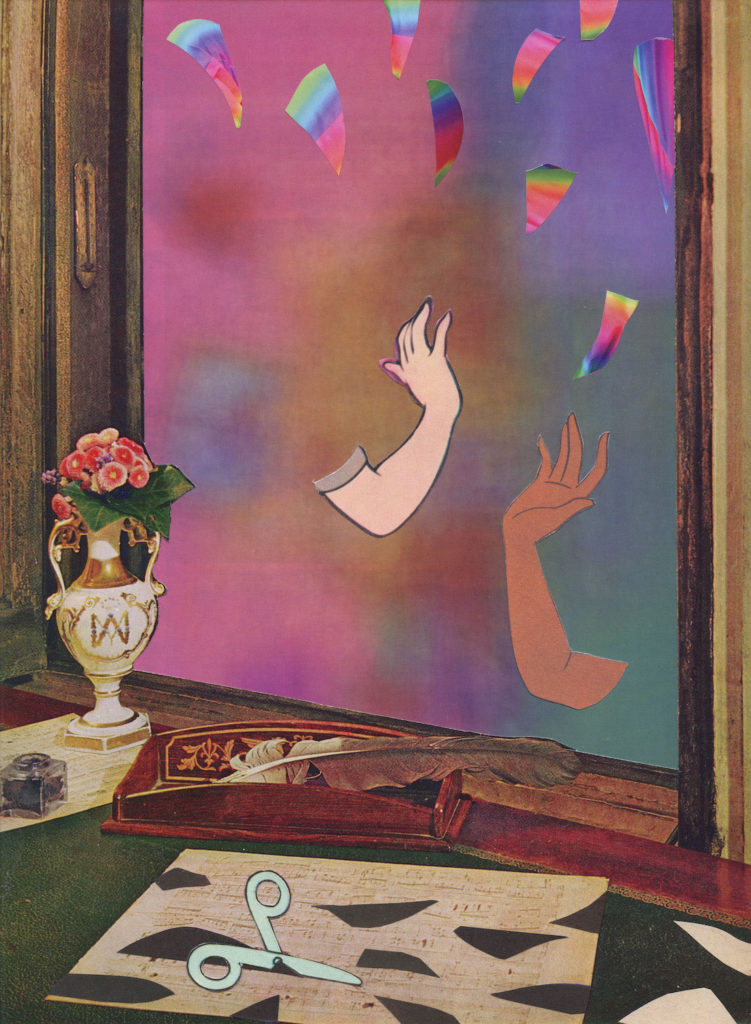

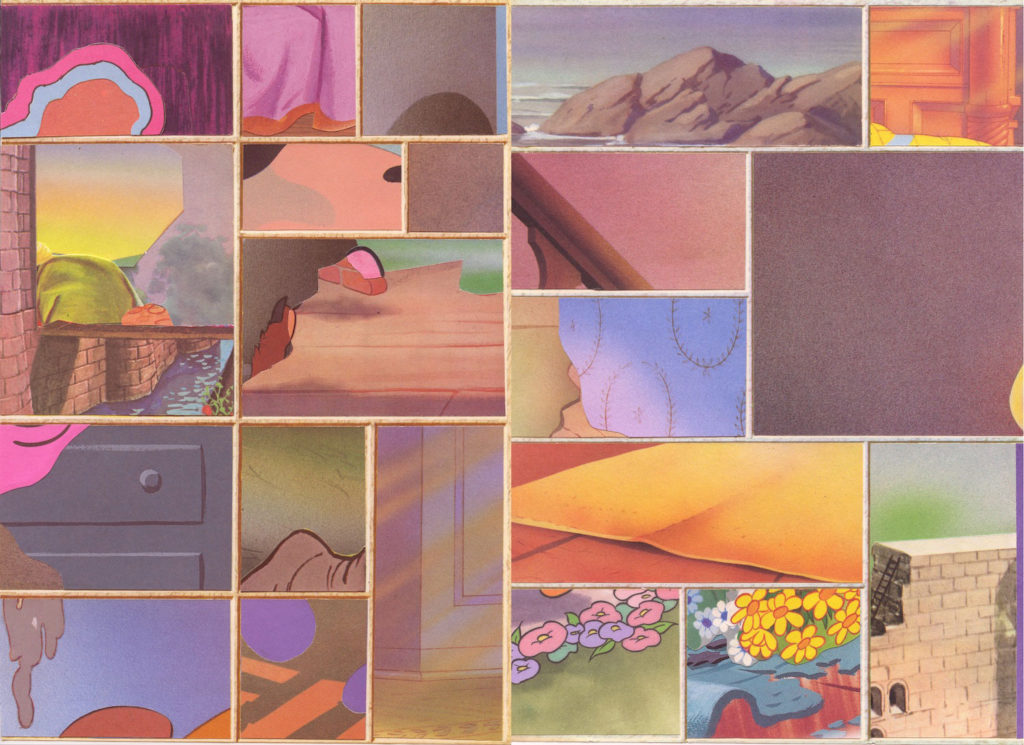

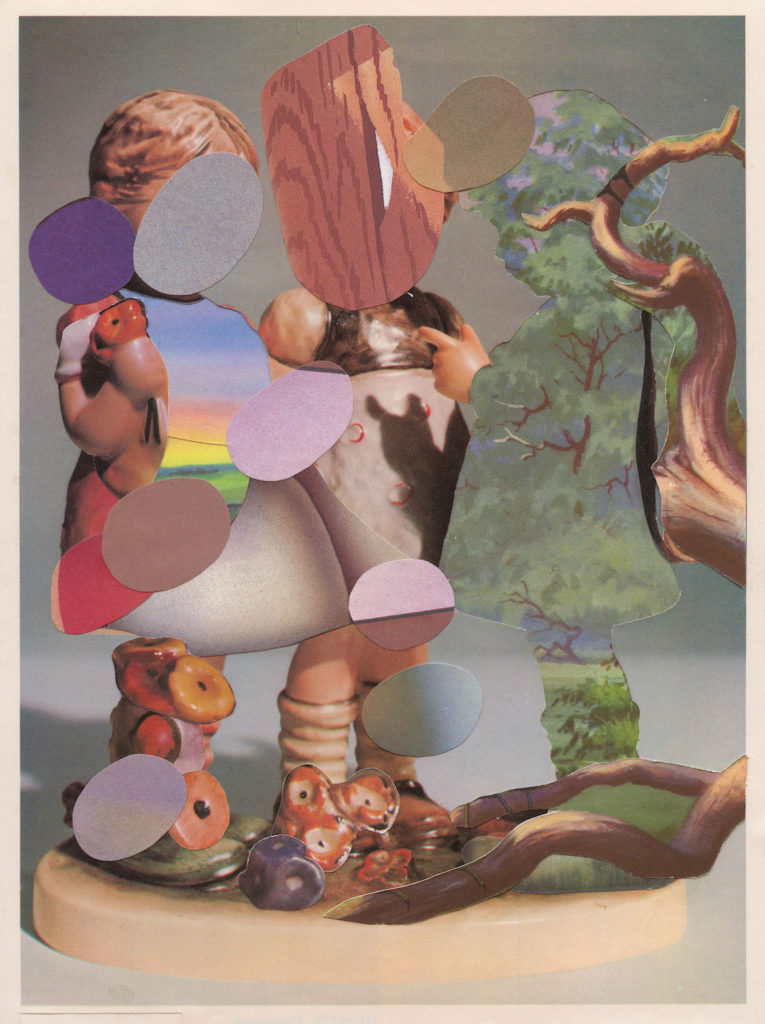

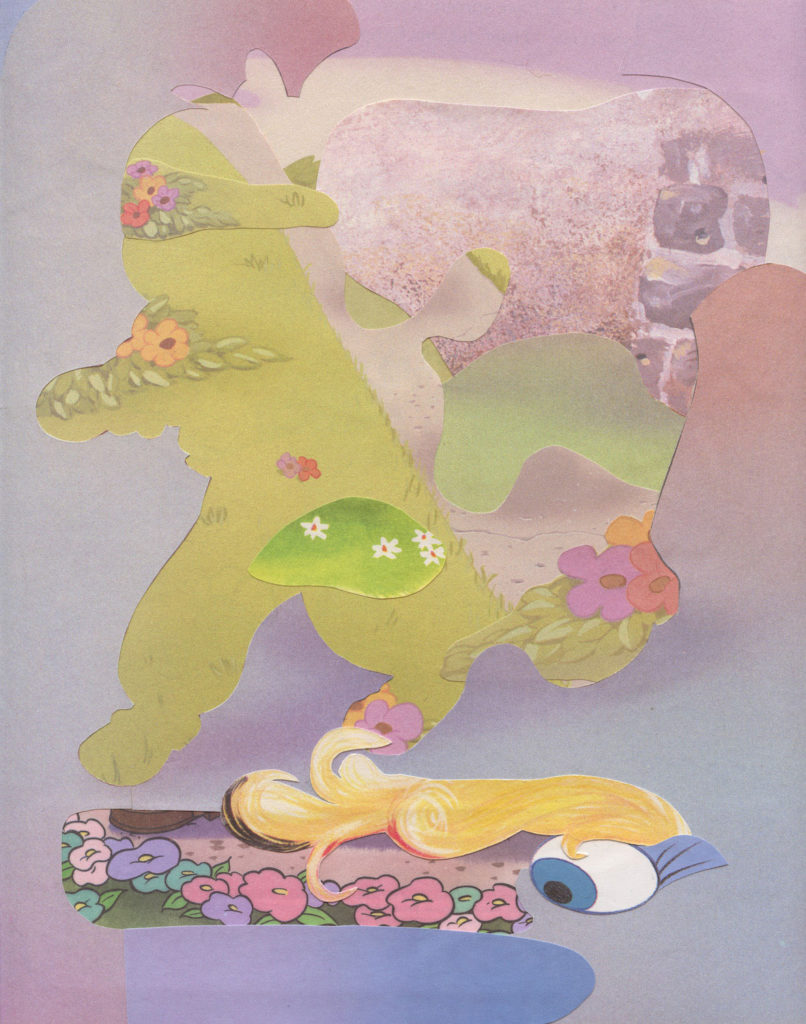

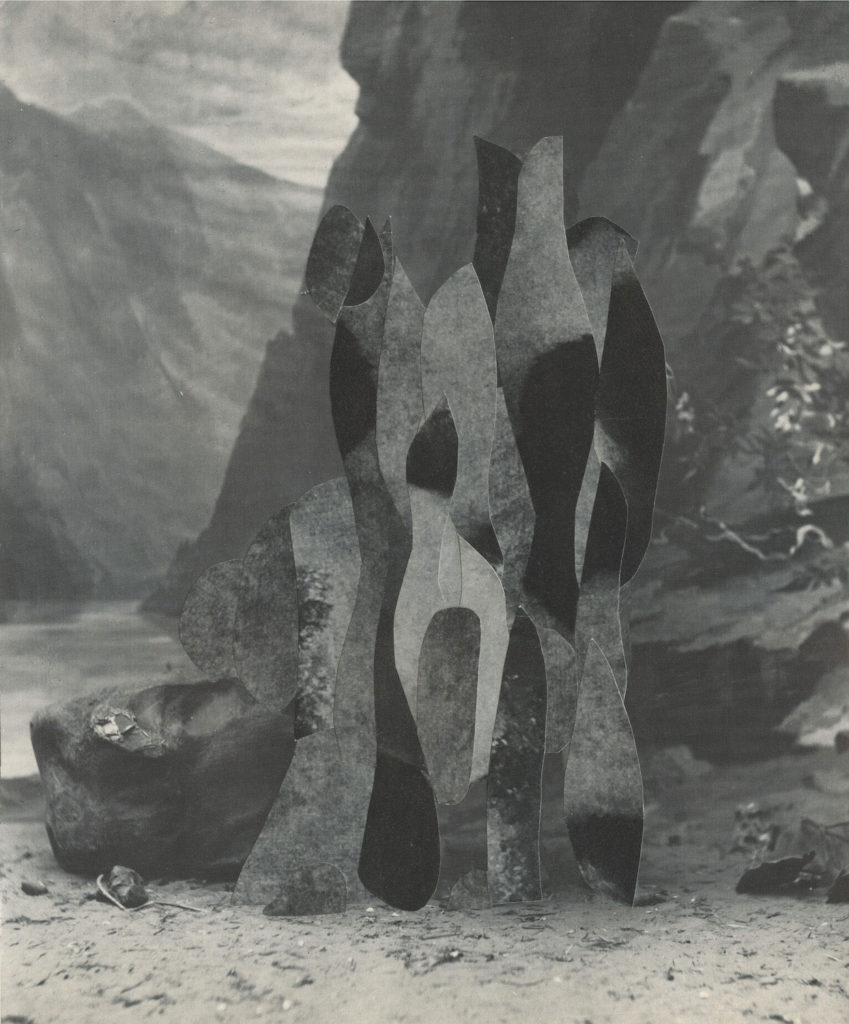

Collage is rooted in its own rich history but it’s also a medium that, by it’s very nature, lives in the moment. The found image is essential, and the act of creating begins with its destruction—this makes sense to me. Images are pervasive shapers of our individual and collective perspective, yet we cannot begin to account for all the images that influence us, they simply are, or were. Their power is in their ubiquity. What I love about analog collage is that not only can I engage with the images that shape my understanding of the world directly—actually hold them in my hand—I can also engage with their histories and the systems that uphold these histories by deconstructing books and other printed material so that images can be reconfigured into being more what they really are, culminations of lived experience rather than static purveyors of specific attributes.

Then there’s the speed. Collage keeps up with my ideas better. Even as my collages gradually become more complex to execute, I get a thrill out of how quickly images and ideas can develop.

TWS –Focusing on your collage work: Your work is full of opposites. Colourful but rather dark. Childish but also trippy. How would you describe your work? What influences have informed it? How has it developed over time?

AM –When I was an art student, I had a studio visit with the artist Nancy Edell. During our conversation, she repeated a question that a senior artist had once posed to her: “What do you want to see?” It’s a question that I routinely go back to when I’m working. There’s power in it because it relies on trusting both your inward and outward vision. Maybe that’s the light and dark you’re referring to. My work is what I want to see.

As for my influences, my long-time partner, Erik Edson, is a printmaker and so I had an intimate relationship with printed material before I started making analog collage. My friends and family and neighbours are all influences. I’m lucky to count Paul Henderson (@oldernowthen) in that group. He showed me a way of looking at collage that was new to me and he has continued to be a huge influence. And of course there’s the online collage community. My kids think it’s hilarious when I refer to it (So what’s happening in the online collage community today?) but living in a small town during a global pandemic, it’s become even more important to me.

TWS –What are your thoughts on your relationship with the viewer? What you want to transmit with your abstract compositions?

AM –The things I’m trying to transmit are foggy and unformed and raw, like dreams. The artist/viewer relationship will always be complicated because most art originates this way, in the peripheries. Most of the time I don’t know what I’m doing or who I’m doing it for. Because it’s gleaned through the process of living, my work is both limited by my specific experience and based in shared experience. To make it, I have to believe that no one and everyone is paying attention.

TWS –Can you walk us through your creative process when making collage?

AM –When I first started collaging, I cut-up eighty or so National Geographics and filed them under titles like “Space-ish”, “Fur & Hair”, and “Ideas in themselves”. I made half a dozen collages with them and then boxed them away. The cutting process is still important to me though. I find it very contemplative. I’m amazed at what I’ll cut-up—guilt free for the most part. I used to be much more precious with books and other original source material. I think the change is a reaction to the increased accessibility of digital images today.

My process is pretty straightforward. It begins with collecting source material at thrift stores and second-hand bookstores. I keep cut pieces and extracted pages in shallow boxes around my studio. I sort through them looking for a particular kind of thing and then find other pieces that, in combination with ones left lying around, become the beginning of a new idea. These new ideas get spread out over surfaces in my studio until they are rediscovered, often much later, during the important process of “cleaning-up”. Many of the pieces then get put back into boxes along with new off-cuts and the process continues ad infinitum. Somewhere in there, I finish some things. I love the element of chance that’s inherent in the mess and the collecting, and the re-messing and re-collecting.

I use blades and scissors, glue and tape.

TWS –What’s your definition of collage?

AM –I don’t feel confident defining collage because I still feel like a visitor to it. The process of moving things around, uncovering and reordering and reimagining? Sometimes you have to tear down, and sometimes time has done some of that for you. This may be the nostalgic part of collage that I respond to. I like using older material because it has been worked on by time. So in many ways, collage, for me, is a process of collaborating with the original creators of the images I use as well as the unseen forces that shape the way we look at and understand images over time.

TWS –Being a painter and a collage artist, what’s your perception of collage inside the contemporary art world?

AM –Because of its responsiveness, I think collage is particularly relevant during this time when the world we’ve constructed is reconfiguring at a pace that can be difficult to navigate. And, in an environment increasingly saturated by images designed to propagate conventions, I think collage is uniquely positioned to disrupt normative discourse. That printed images are becoming more and more obsolete in the wake of digital information makes them all the more appealing as material—they’re both metaphorical and actual debris. Analog collage using found material inherently speaks of the currency and lifecycle of images. It questions our creation of histories and the role of nostalgia within those histories, and it activates the complex relationship between individual and collective experience.

More Andrea Mortson on instagram and at Galerie 3