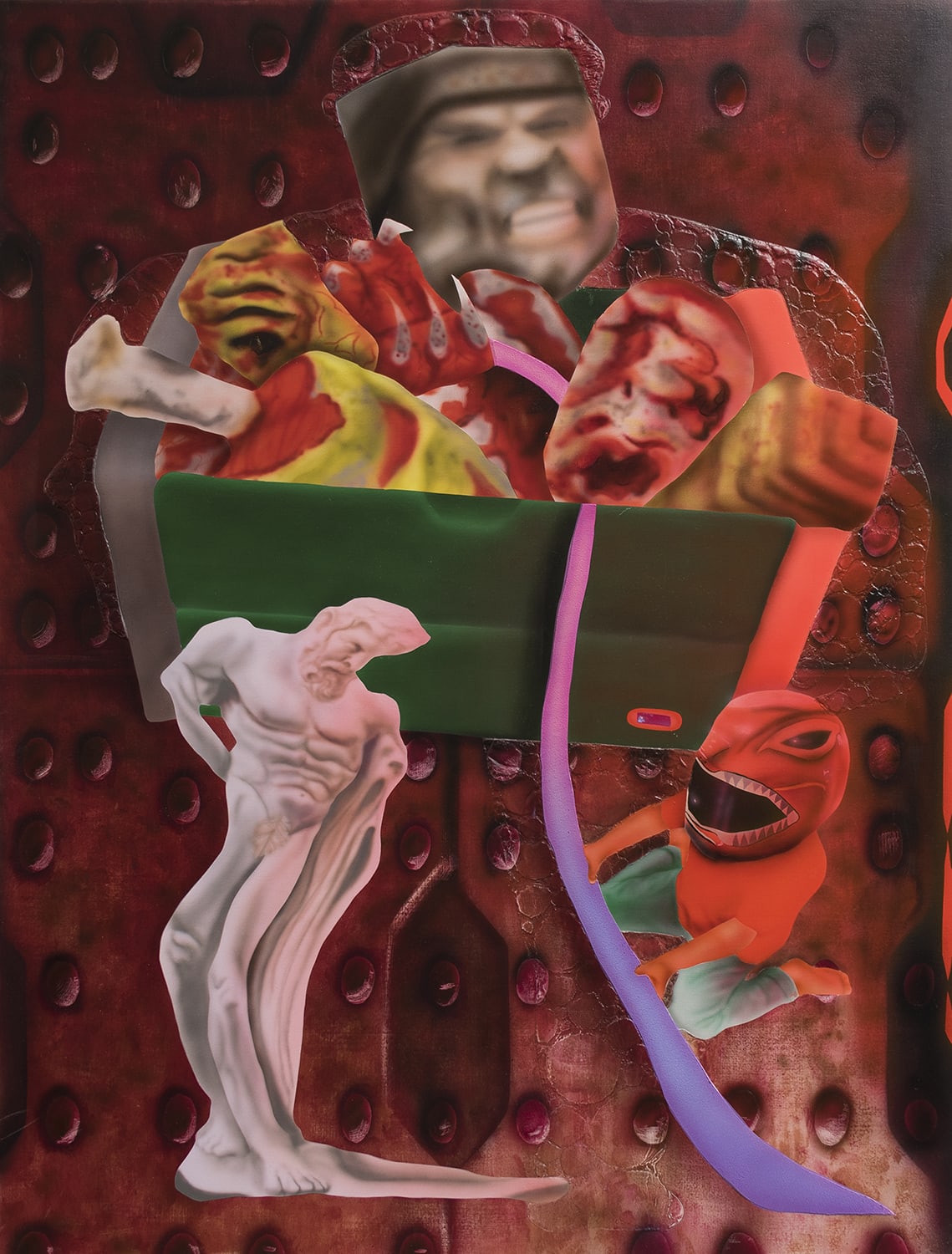

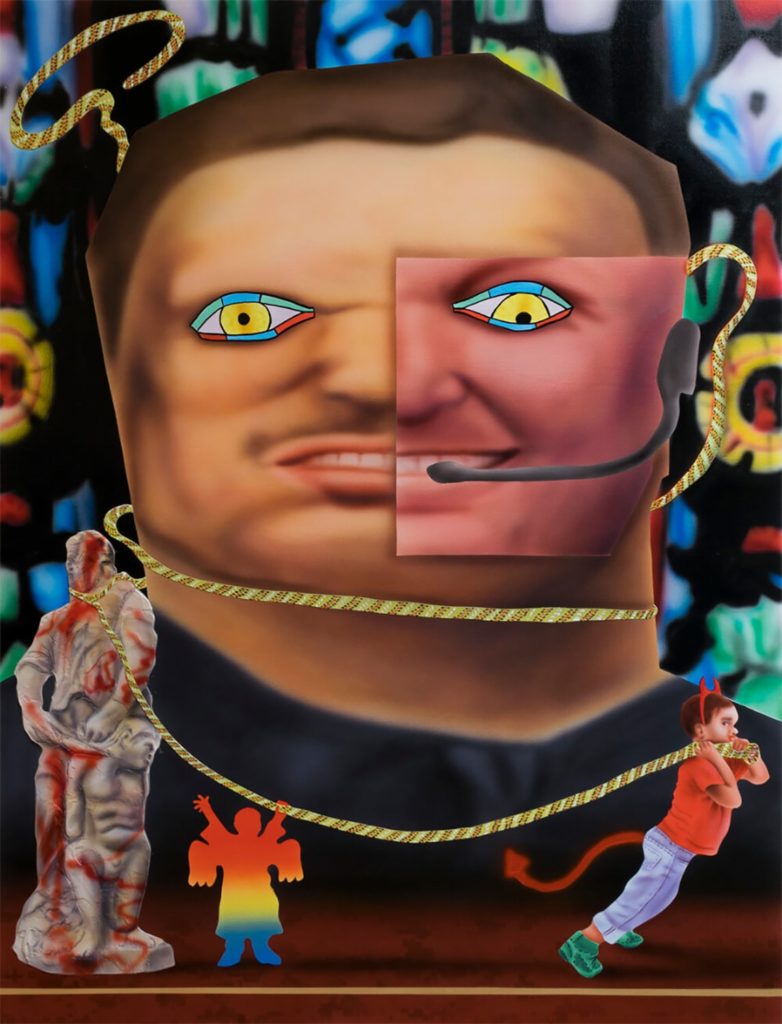

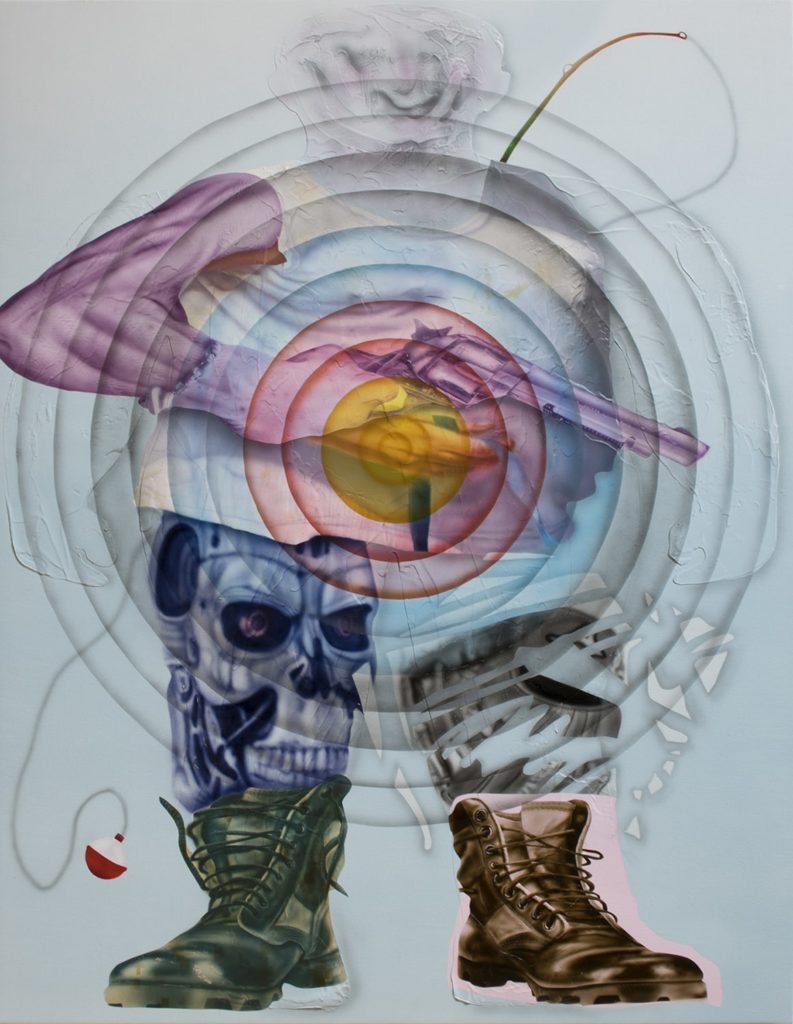

Chris Regner is an artist born and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, who currently resides in Providence, Rhode Island. He works serially, using autobiography as a jumping-off point for satire, humiliation, and explorations of the grotesque. His work tackles a variety of topics, including religious and cultish indoctrination, the effect of technology on societal discourse, how to navigate adulthood as a male with no strong role models, and stereotypical notions of masculinity that find their way into every subject he explores. Using his personal experiences as a foundation, his paintings have questioned archetypes found within these themes, all the while challenging his own values and beliefs. He positions himself as an anti-proselytizer, complicating the easy answer and presenting morally questionable individuals with the intent of causing contradictory interpretations by the viewer. Navigating this discomfort is vital when searching for a greater truth.

Chris is a recent graduate of RISD’s MFA Painting program. He has shown his work in shows nationally. His work is a part of multiple private collections internationally.

TWS –Hi Chris, can you tell us something you’d like people to know about you?

CR –I almost went to school for fingerstyle guitar.

TWS –You mention that you use autobiography as a jumping-off point for satire, humiliation and explorations of grotesque. Has making your art helped you to overcome or approach in new ways the issues that you address in your work? How does putting this issues out to the world has worked with you so far? Have you been able to navigate your discomfort better thanks to your work?

CR –I’m not sure if making art about myself has helped me overcome anything, but perhaps framing these events in a different, productive manner has been cathartic in a way. I try not to overthink it as I feel there’s a danger about falling into an angsty trap when making personal work. There needs to be a bit of distance to communicate more effectively.

I’m generally a pretty open person if you ask me things, but I don’t like to overshare if I feel it isn’t wanted. In this way it was a hurdle to make more vulnerable work, but I’ve been happily surprised by the positive reaction. I think some of what I experienced growing up is relatable, so I’m very grateful that others can feel a connection to the themes.

I have been able to become more comfortable with this approach as I go. I still feel uncomfortable painting some of the things I do, but I think that’s generally a good sign I should do it. It’s fun being a little risky and to pushing boundaries. Peter Saul is a hero of mine, so I’m drawn to that sort of thing.

TWS –You also mention that you are a “Anti-proselytizer”. Can you explain us what that means and how you manage to be so through your work?

CR –I’m incredibly skeptical of ideologies that promise utopian visions. I’m also distrusting of art where the sole function seems propagandistic. Art is one of the only venues for human expression where I truly believe an individual can transcend herd mentalities and offer a relatable, nuanced, personal view on difficult topics. I want to hear what YOU think. I suppose in this way I’m an idealist. I want my work to be complicated in a way that goes beyond “right” or “wrong”, “moral” or “immoral”. I’m not interested in convincing the viewer to join a side. I want the viewer to be conflicted, uncomfortable, and have to contend with their own morality and sensibilities. It’s not an artist’s job to conform to your world view and it’s not the viewer’s job to conform to the artist’s. This conflict is one of the reasons art is so beautiful.

TWS –Being your work so driven by your personal experience, where does a series start? In the need of addressing an issue? Or your work start visually and it slowly conveys into subjects you want to explore?

CR –A series generally starts with an annoying obsession that I have been contemplating as of late. This varies quite a bit. My old work dealt with working at an art retail store right after graduating college and how frustrating I found it. Another series dealt with political ideologies pushing into cultish, religious territory, which I find myself constantly thinking about, despite my best efforts. My more recent, personal work has stemmed from my own experiences as an adult man and how I feel I failed in some aspects of my life and where that stems from. So to summarize, nagging frustration is my fuel I guess.

My work generally starts as concepts and I build the visuals around it. I decide the best style to use for the topic and go from there. Lately this has changed as I feel I am settling a bit into a way of painting, and now I find myself reacting to things that happen through the act of making the work. This is new for me, but I find it exciting. There are surprises that happen in each piece that I can now build on with subsequent work.

TWS –What are the role of titles in your work?

CR –Titles can act as a way of injecting humor or meaning into the work. I am deliberate about how I choose to title my pieces, as I find this can be vital to deciphering the mass of symbols. I want the title to act as a guide of sorts to pick apart the minutia, and to have that understanding build up as you start to put the pieces together. I also wish to convey that these paintings are supposed to be reveling in their pathos, and that you can laugh along with them and at them. A lot of my themes are quite dark, but I want pity and humor to humanize the subjects depicted and put the viewer’s judgments on hold. I’ve been watching Twin Peaks again recently and I find that David Lynch taps into that sort of emotional whiplash with his characters perfectly. That’s the reaction I aspire to.

TWS –There are personal, artistic and cultural references layered and blended together in your work. Can you walk us through some of your most relevant influences that helped you to have your own and unique way of making your art?

CR –I tend to pull from all of my hobbies, interests, and inspirations. I don’t like to categorize them as high-brow vs. low-brow. Everything is valid and if it is relevant to the concept, it should be used. Some major influences to the aesthetic choices in my work have been the Chicago Imagists, German Expressionism, Baroque painting, crappy CGI, video games new and old, video game engines, kustom kulture art, pulp sci-fi illustrations, and film. I try to throw a bunch of these together in each piece in an organized fashion where they can all play off each other.

TWS –Airbrush and soft shapes had become a big part of your latest work. What does the airbrush has that attracts you? What role has the airbrush look in the construction of your discourse, where the grotesque somehow collides with the softness of the lines painted with this tool?

CR –I was initially drawn to the airbrush as a way to emulate the digital collages I was painting from. This quickly evolved into a love for the tool and all the possibilities it presented. I majored in drawing in my undergraduate education and never completely developed a relationship with traditional methods of painting. I primarily used graphite and charcoal, building up layers slowly. The airbrush is very similar to this, so it was a natural fit. I began focusing on learning how to render convincing images with this tool in the past 2-3 years and now it has become my go-to way of painting.

I’m generally intrigued by activities and hobbies where you have a limited tool set or strict rules and it’s up to you to find the creativity within these limitations. The airbrush is versatile but it can be a hurdle to offset its default appearance. I try to counter this with varying edge quality, stenciling, xacto blade scratches, and acrylic medium grounds. It’s an enjoyable challenge to make the same tool look different within the same painting.

There’s something about translating grotesque images into painting and drawing that beautifies them; makes them easier, if not desirable to sit with. There’s a distance between you and the wretchedness that makes it palatable. I think the seductively soft transitions with textures and values achieved with the airbrush heightens this effect.

TWS –Although your work is all handmade (paintings, drawings or sculpture), there a digital feeling to many of your pieces. Some elements seem to have passed through photoshop filters or through their transformation and perspective modification methods. What’s your feeling about this? How do you relate with digital tools? Are they used anyhow in your work?

CR –I want my images to feel fake, as if they are a bit distant or detached, but to allow room for depth and feeling. My collages are made via Photoshop where I manipulate, edit, and filter each piece and fit them into a grander whole. I used to fight against the inherent awkwardness of this but I eventually decided to embrace it. I think it fits into the general theme of failure and embarrassment. In my Father Figure series, for example, I consider what it means to not have a true figure like this in one’s life and how one finds it through different means. These experiences are found through through digital interaction (message boards, video games, etc.). I want these to feel artificial, but not without their personal touch. Emulating digital language, such as drop shadows, gradient maps, and saturated, poppy color plays a role in the concepts of distance and mediated experiences.

TWS –There is a very thoughtful and committed search for imperfection in your work. What does this imperfection means to you? What do you want to say through it?

CR –It’s important that the subjects I portray feel awkward. The pieces don’t quite fit together, or the edges are warped and janky. I’m not looking to provide a seamless image that feels realistic and convincing in a traditional sense. Failure and imperfection are paramount to most of my concepts. I feel that it is more reflective of the inherent human spirit to strive to be better, to be more, to be as perfect as one can expect to be. This is limited by our imperfections, psychologically, physically, or otherwise. Therefore, I find it more relatable and realistic to address the impossibility of utopia. I think within this admission of imperfection is where the personal relationship to a piece of art begins, for the viewer and the artist.

TWS –Has collage interested you or influenced you somehow? Do you see collage as a relevant conceptual aspect of your work?

CR –I’ve been enamored with the idea of collage ever since learning about the way the Cubists constructed theirs. Putting disparate items together that somehow still relate to the larger image has been a guiding principle of my work. Picasso’s Guitar, Sheet Music and Glass collage was transformative to learn about and I haven’t stopped thinking about this piece since. I strive to have every collaged image encapsulate its own history and identity that not only form a whole paragraph but also operate as statements of their own.

TWS –Finally the only question we ask all the interviewees: What’s your own and personal definition of collage?

CR –A puzzle constructed of puzzles.

More about Chris Regner on his website or instagram!