One of our dreams when TWS started was to interview one of our art heroes: John Baldessari. In fact, our first 7 question interview included the question to all artists: What would you ask John Baldessari. When Baldessari died in January 2, 2020 we realised that we never will be able to ask the man all the questions we had gathered along the years for him. So now I thought that we could do something to both have him on TWS and honor his tradition, and the best we could come up with was a collaged interview. So we read many (many) interviews with the artist and collaged* some questions to create our own interview. So without further introduction, here’s John Baldessari’s collaged interview. (*All sources/original interviews are be available with the interviewer’s name).

John Baldessari – Hello?

Henry Ward – Hello, is that John Baldessari?

JB – This is he.

HW – Hi John, it’s Henry Ward here, calling from London….

JB – Oh hi yes, I was expecting your call.

HW – It’s ok to talk?

JB – Yeah, that’s fine.

Charmaine Picard – You have said that as a child you felt like an outsider because your parents Hedvig Jensen (b. Denmark) and Antonio Baldessari (b. Italy) were immigrants. Did this influence your work?

JB – Having to explain myself to them in the only language I knew, which was English, made me think about how to communicate and how to make things clear. My father died at around 100 years old and even then he spoke broken English.

Nicole Davis – What led you to become an artist?

JB – I always had this idea that doing art was just a masturbatory activity, and didn’t really help anybody. I was teaching kids in the California Youth Authority, an honor camp where they send kids instead of sending them to prison. One kid came to me one day and asked if I would open up the arts and crafts building at night so they could work. I said, “If all of you guys will cool it in the classes, then I’ll baby-sit you.” Worked like a charm. Here were these kids that had no values I could embrace, that cared about art more than I. So, I said, “Well, I guess art has some function in society,” and I haven’t gotten beyond that yet, but it was enough to convince me that art did some good somehow. I just needed a reason that wasn’t all about myself.

Eleanor Morgan – Is it fair to say that in the beginning of your career you were trying to break certain gallery taboos?

JB – I had a few battles there, yeah. But it certainly is true: I wanted to challenge, and ultimately break, all these taboos that art galleries had at the time. You never saw photographs in art galleries— they were always in photo galleries. So I wanted to make photography a tool that artists can use, as opposed to something they can only, well, look at.

EM – You did the same thing with introducing text into your work.

JB – Absolutely. I became very interested in the prospect of using language as a tool for art, and informing the work in a different way. It wasn’t just about the visual appearance of the language, either. It was about giving a different platform for understanding the work. Most of the text was “found,” as well—broken signs, segmented newspaper headlines, things like that. I just appropriated bits of it and gave it a different course.

Moira Roth – If you were interested in language, why didn’t you write?

JB – Well, I guess I’d always wanted to. All through school, I could always spell very well, write moderately well, and always loved looking up words. Words have always been a fascination for me. They’re so very magical. And words just seem to me a very viable material to use in a creative way. We always think about using forms in some creative way and that seems interesting to me, but no more interesting than using words.

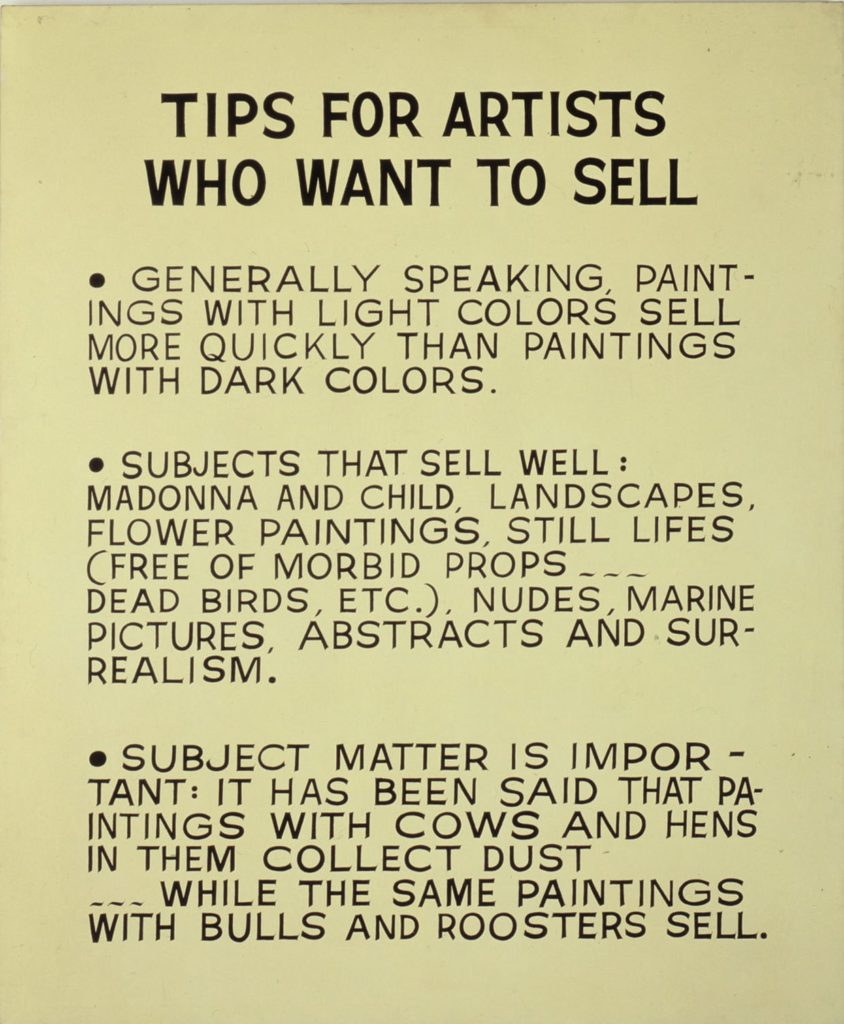

Yasmin Bilbeisi –This brings to mind one of your early text-based paintings that gave artists advice on selling their work.

JB – Oh, yes, you’re thinking of a piece called Tips For Artists Who Want to Sell?

YB – This was a tongue-in-cheek commentary on art instruction books. How do you think this piece would be received by today’s artists or in today’s market?

JB – (laughing) Here is an interesting comment on it: Jeff Koons, who I used to show with at Sonnabend, says that’s his favourite work of mine! “And why is it your favourite work Jeff?” … Because it’s precisely the kind of work he does. I think there is this assumption that the higher the price, the better the art. Which we know, of course, is not true. But if something sells for five million dollars, ipso facto, then it must be really good … which is not necessarily true, of course.

Andrea Blanch – What would I have learned if I was a student in your class?

JB – I haven’t taught in years. I believe in the trial and error thing. One thing doesn’t work, you try another thing, and I remember one of the students, Matt Mullican, who is a pretty famous artist now. He did a piece where he had somebody at the entrance of CalArts with a mirror that caught the sunlight and then somebody at the door caught that sunlight and somebody else caught that until the sunlight entered our classroom and the piece was finished. That was quite inventive I think.

David Salle – I remember this girl once—she had these very romantic ideas about art. She asked me, “Where do you think your art comes from?” And I said, “Other art.” She got totally turned off.

JB – Don’t use that line again.

Henry Ward – Ok, John, I’ve got one last question…

JB – Sure.

HW – You’ve referred to this already, and I think it’s an amazing thing, a Youtube sensation, this video. In the brilliant “A Brief History of John Baldessari”, narrated by Tom Waits, you said that you thought you might be remembered as the man who put dots on peoples’ faces. Your legacy to the art teaching profession, however, is undeniable and you are an incredibly inspiring figure in this field. How do you feel about the prospect of being remembered as a great artist, but also a great teacher?

JB – I don’t really care about being a great teacher. I just want to be remembered as a great artist.

HW – It’s a good answer but I think you will be remembered as both.

JB – Well I hope that my answers have been of use to you?

HW – Yes, thank you very much.