By Andrea Burgay

Before stepping into Edgard Barbosa’s studio, I encountered his work in two distinct ways. Initially, I had seen images of his collages online, where fragmented luxury goods and models, arranged in intricate grid formations, appeared seamlessly composed, leading me to assume digital processes were at play. Later, at a collage event I hosted, I noticed Edgard working at the collage table. Upon his departure, I discovered a perfectly folded piece of collage origami left behind.

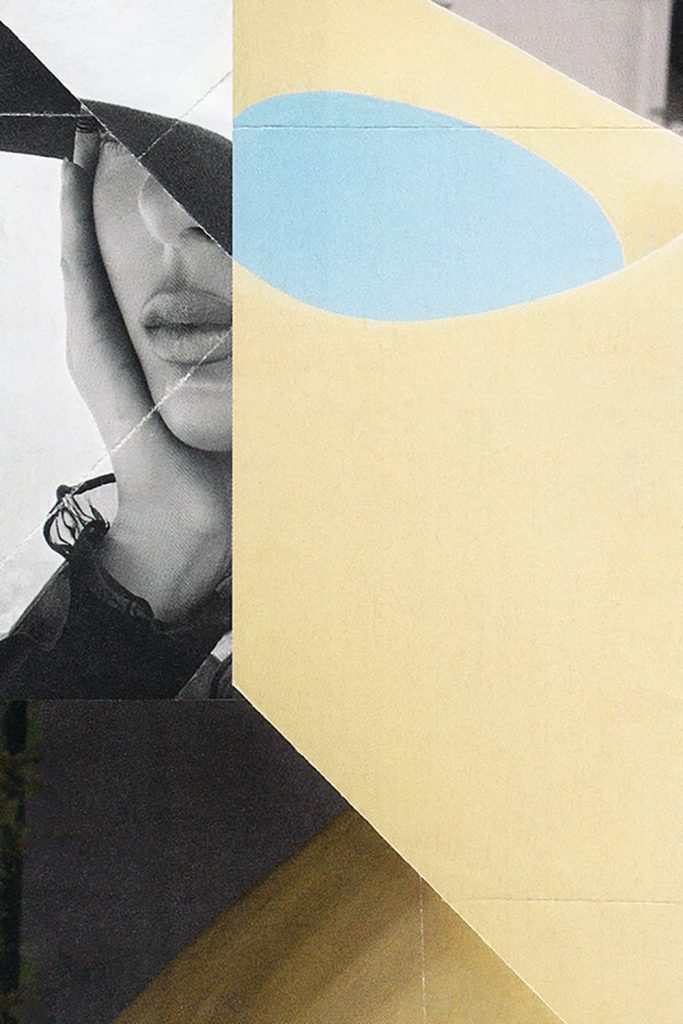

As I continued to look at his work on Instagram and his website, I started to recognize shapes reminiscent of the origami form I found and noticed tell-tale fold lines. Curious to learn more about how these dual collage approaches manifest in Edgard’s work, I visited his studio in Washington Heights, New York City.

AB –Can you guide us through the process of your latest piece, starting from the initial physical photograph, to its digital transformation, and culminating in the final physical manifestation?

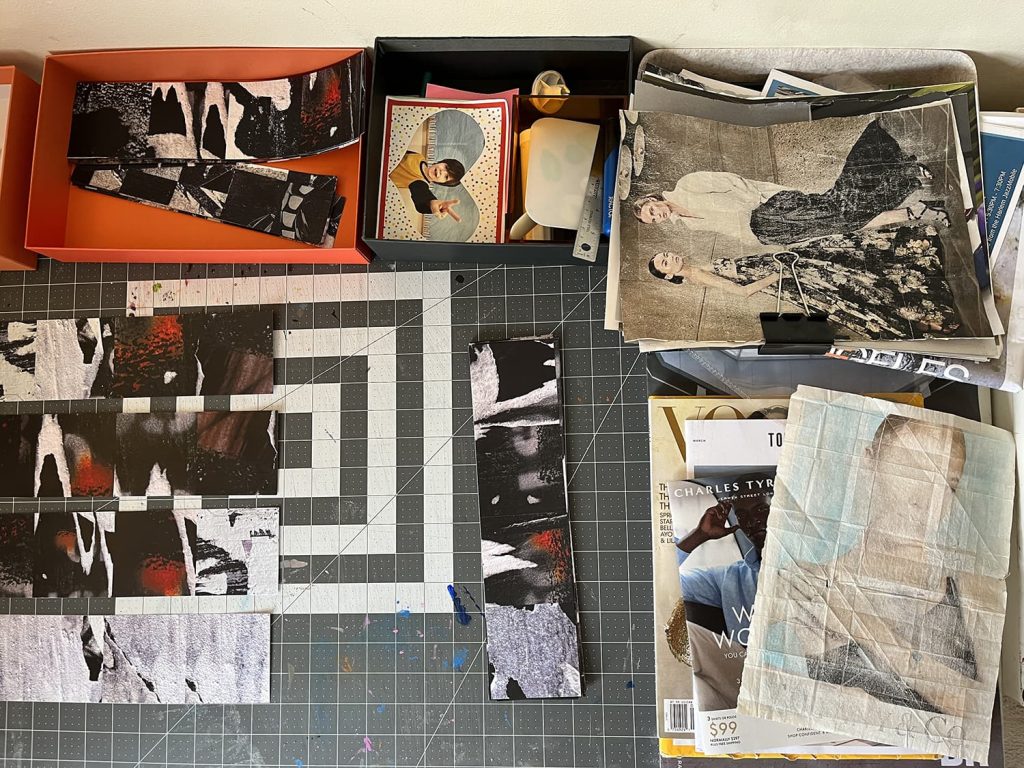

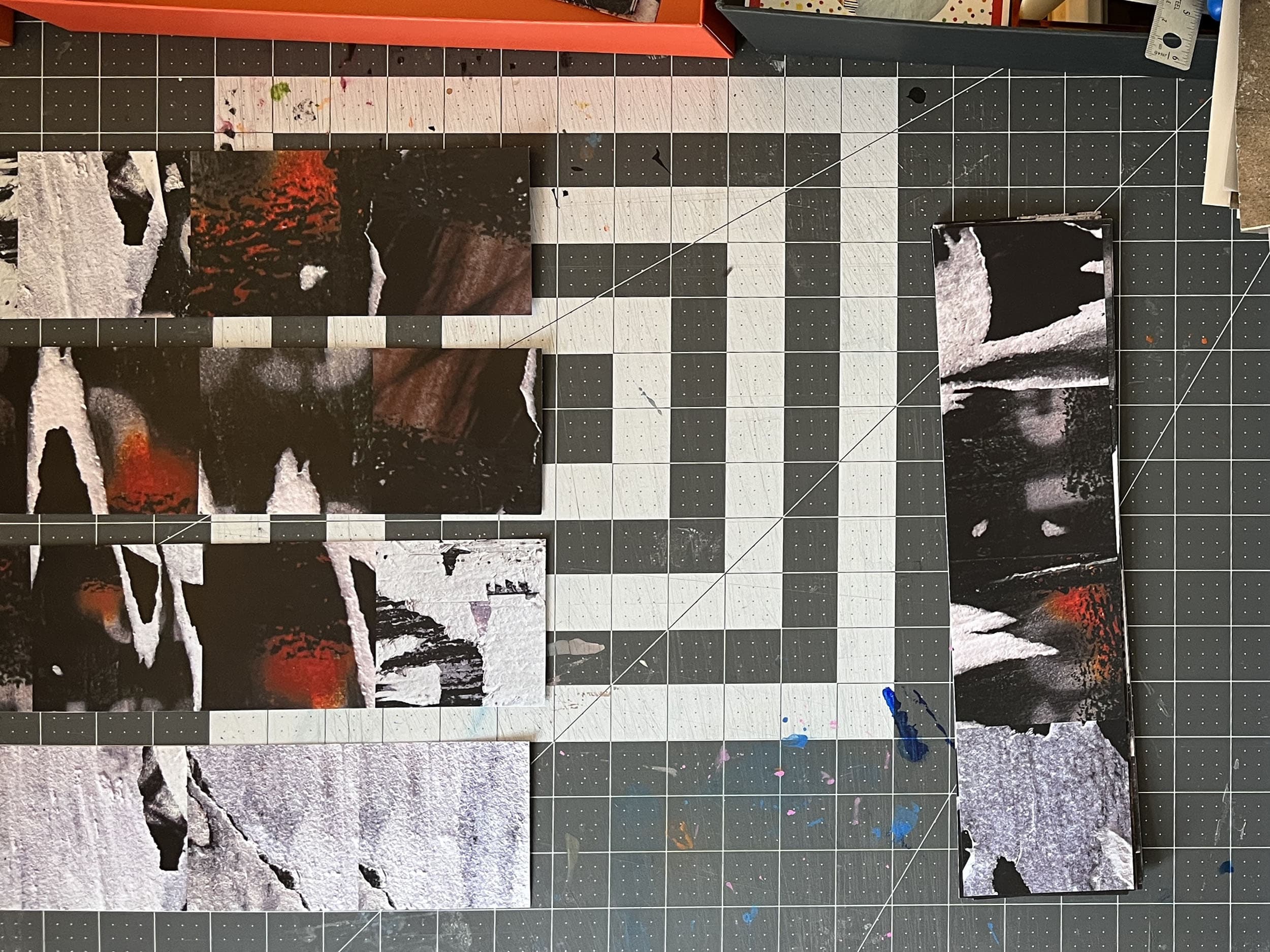

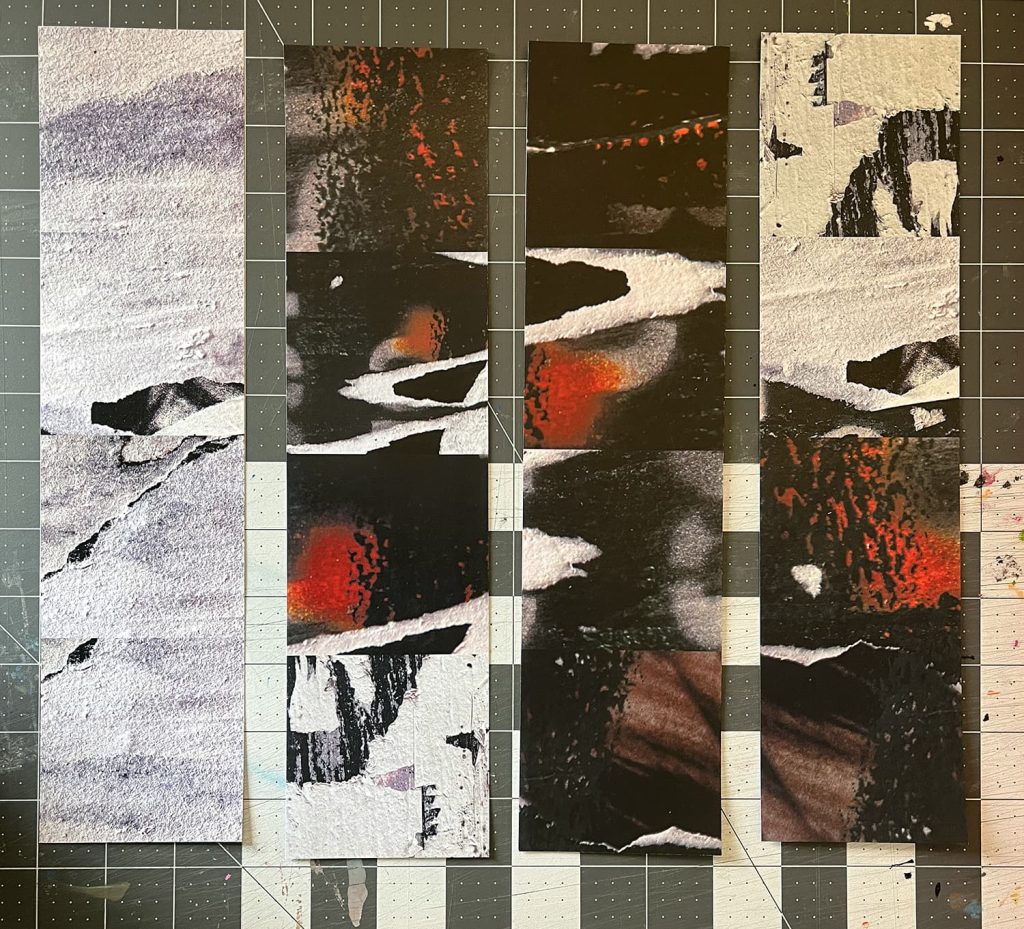

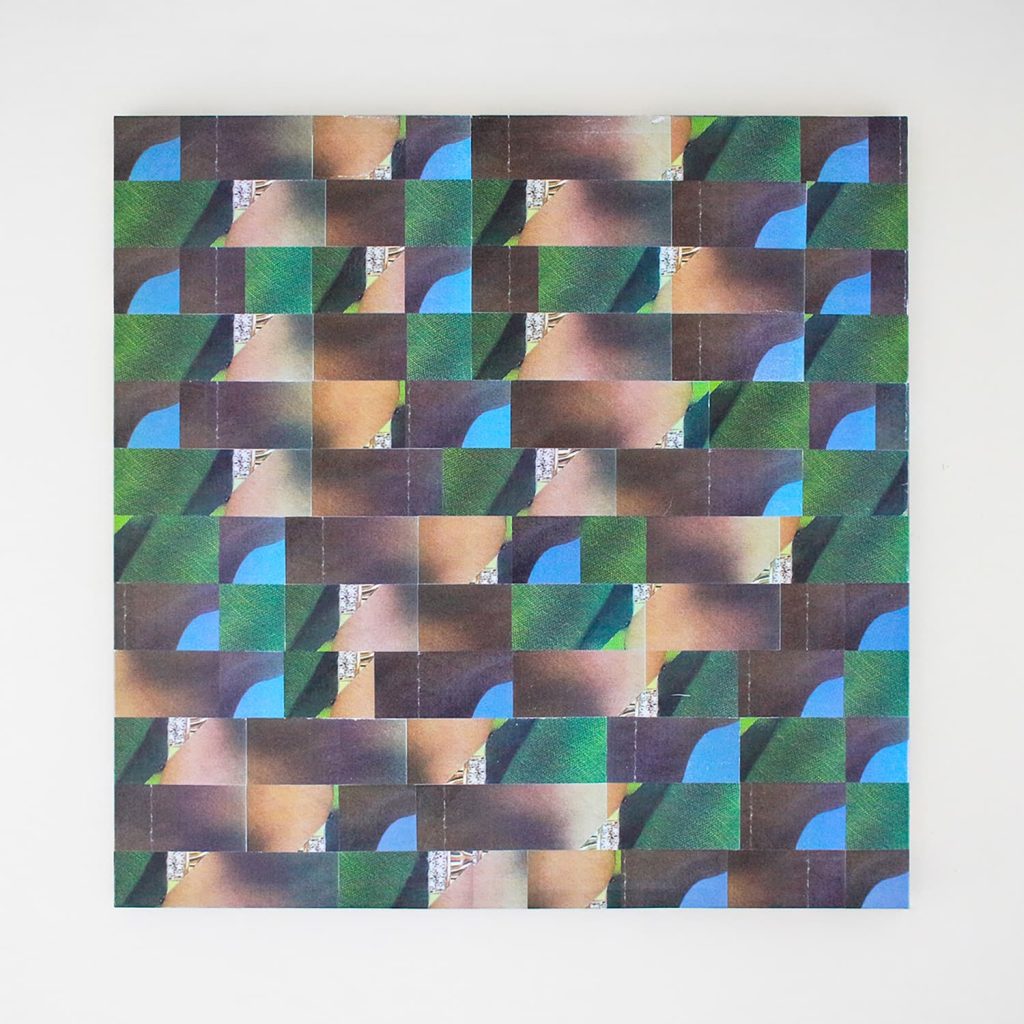

EB –For my latest piece, I borrowed my friend John Marks’ Canon EOS R5 and went around Chelsea and SoHo taking pictures of posters pasted on construction site fences. I took hundreds of pictures and narrowed them down to two. I did some light editing of the final images using various Adobe Suite apps. From there, I cropped them into over 100 different squares measuring 3×3”, arriving at the latest, or final, iteration. Then, I printed the squares at Staples and wheat-pasted them onto canvas. The entire process, from photography to prints, took me a month, while pasting took just an hour.

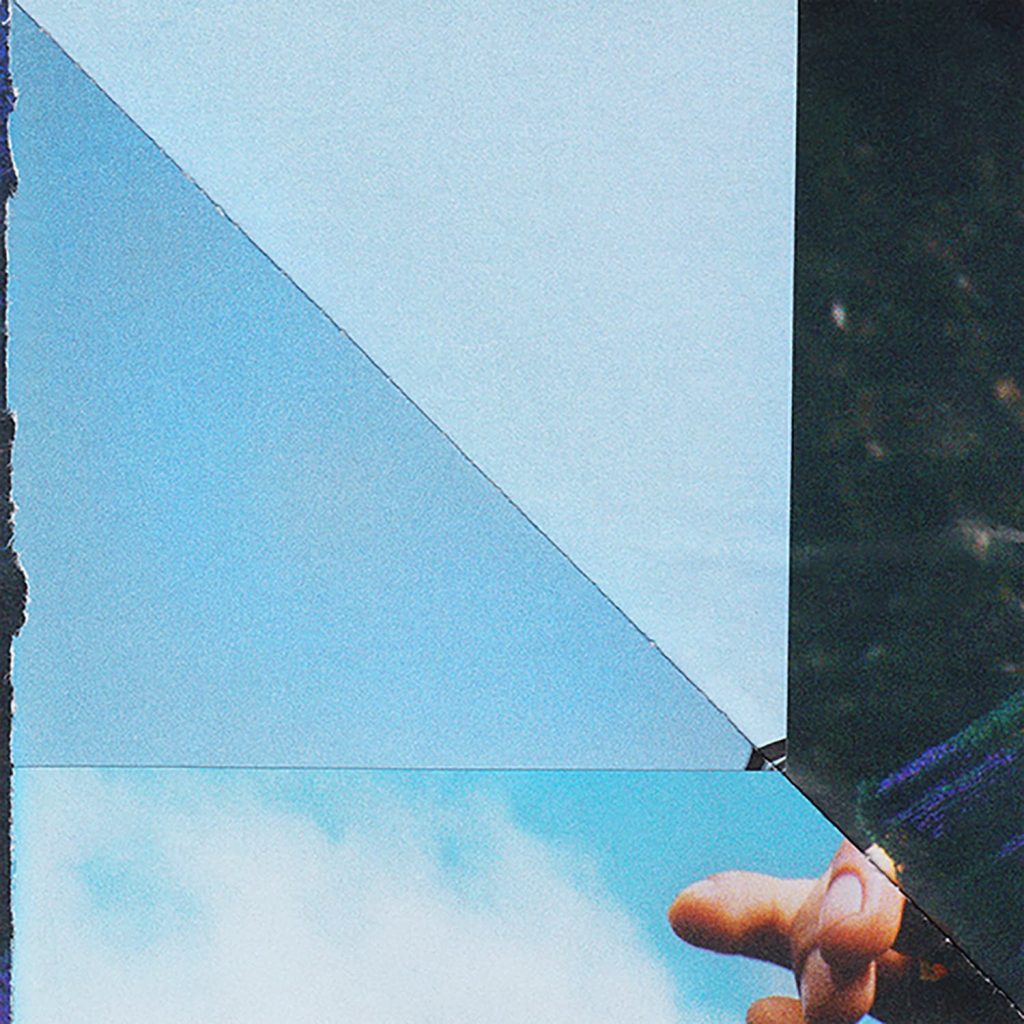

AB –What motivated your incorporation of photographs of urban layered paper into your recent works? What thematic messages or responses to these sites do you aim to convey through your unique approach?

EB –I like to work from current sources, and there’s nothing more immediate than advertising sourced from the street, especially fashion advertising. I also see it as archiving. These images will go out of style within months and will never be current again. I believe it’s important to have a record of these images in their relevant environment at that specific time.

AB –How do you approach using magazines as source material versus advertisement posters from urban landscapes?

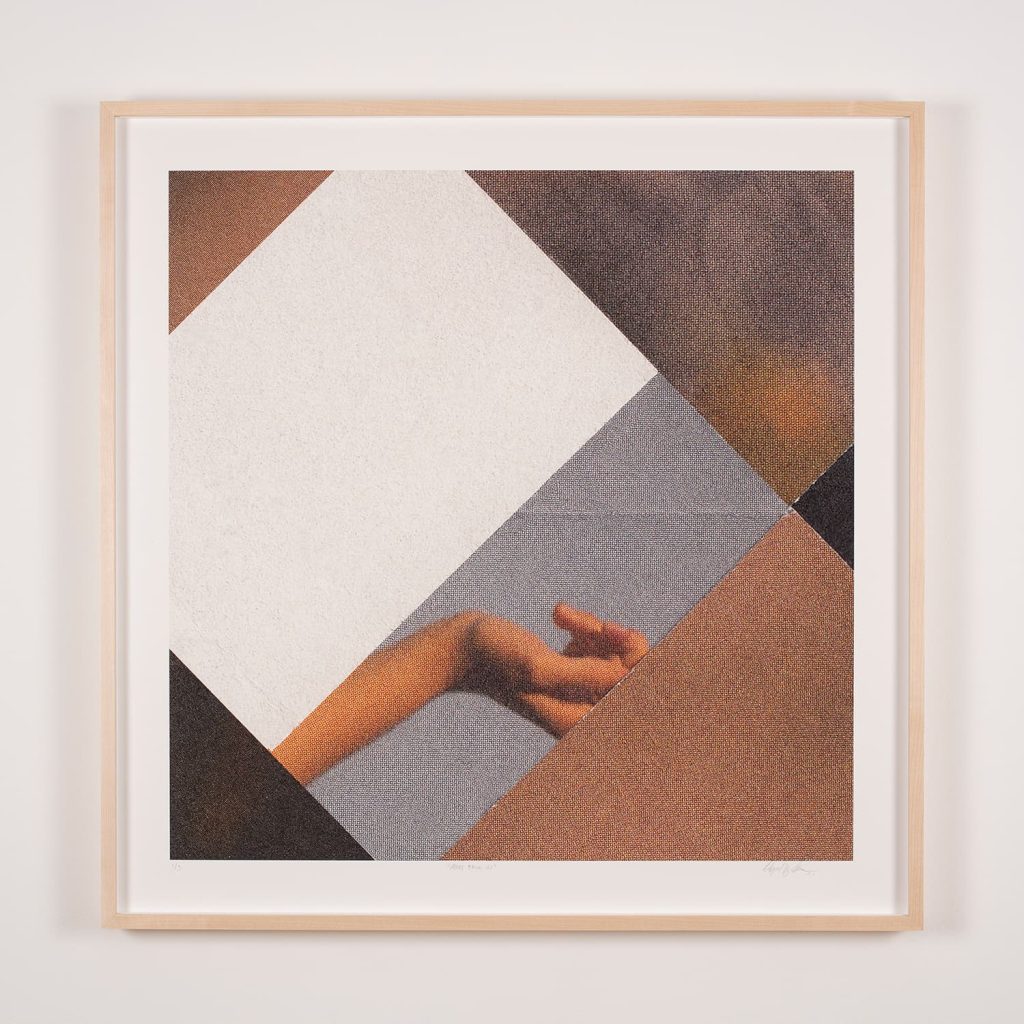

EB –The thinking is similar, but their environments differ, and I adjust my expectations accordingly. The constant is that the images I seek out revolve around what is considered luxury and wealth today. However, the difference lies in the fact that magazines present perfectly manicured expressions of those messages—completely unblemished. Street posters, on the other hand, are dirty, often destroyed, and reflect how we actually interact with ads when they are unsolicited. Dot densities vary, scale differs. Ultimately, though, my approach remains similar: abstracting, overlaying, and repeating. It’s the same language but spoken in different dialects.

AB –We talked at length about the role of grids in your work — both in organizing relationships and breaking conventions. Can you elaborate on how you both employ and disrupt grids within your creative practice?

EB –I find that I devote most of my thought process to grids. I’m fascinated by the concept of the grid as an invisible tool for organization, space-making, and communication. In my work, grids serve the same purpose.

They form the foundation of my understanding and act as my starting point for approaching a surface. From there, whether I adhere to or deviate from the grid depends on its interaction with the sources at that moment. It’s the eternal conflict between what the grid dictates, what the sources demand, and what I envision. I perceive myself as the mediator and executor in that ongoing dialogue.

Orange, Lilás, and Rolex, 2023

AB –Building on the theme of grids, we explored their significance in urban planning, in both our current setting, New York City, and your hometown of Petropolis, Brazil. Can you expand on your ideas about grids on a broader scale, considering their role in fostering beneficial systems as well as exerting control?

EB –While my hometown has the claim of being the second planned city in Brazil after Recife, growing up I wasn’t at all aware of what a grid was. I did, however, have spaces in town that were, somehow, “placed”. The grid became real to me when I first moved to Florida, as a teenager. Moving to a new country made me hyper aware of the idea of place.

Petropolis is very much a 19th century product, and moving to car-centric Florida, then hyper-efficient New York City was a real adjustment to me personally. What I realize now is that I was exposed to a variety of ways to understand and organize space.

The grid was the primary baseline tool that those urban designers used to express their specific values of efficiency, organization, clarity, and, on the other side of it, division and delineation. These cold, academic principles of design and planning all evoke emotional responses. They came to define home and homesickness to me. It defined my time growing up and growing away. It has become a source of power and comfort for me. In a world where everything shifts, I can always refer to a baseline that remains constant.

AB –We also talked about “The House of the Seven Errors,” a building in Petropolis that may have been another visual inspiration. Can you describe this building and its connection to your ideas regarding presenting duplicate artworks?

EB –Up the street from my school lies a tourist attraction known as ‘A Casa dos Sete Erros,’ which translates to ‘The House of Seven Errors.’ Since childhood, I’ve been captivated by this historic 19th-century home, even though I’ve never delved into its history. What draws me to it is its architectural quirk: each side of its facade features seven distinct differences, resembling an architectural game of spot-the-difference.

What’s intriguing is that at first glance, the house appears ordinary and handsome, without any extravagant embellishments. However, engaging in the game reveals its whimsical and almost magical charm through subtle details. This concept of repetition with unique variations has fascinated me ever since. I strive to create compositions that establish a cohesive visual language while incorporating hidden details—much like the ‘easter eggs’ found in video games or movies.

Once you’ve identified the differences on the house’s facade, you’re compelled to keep looking, hoping to uncover a concealed eighth error that no one has spotted yet. This pursuit of discovery sets a high standard of design excellence that I aspire to achieve in my own work.

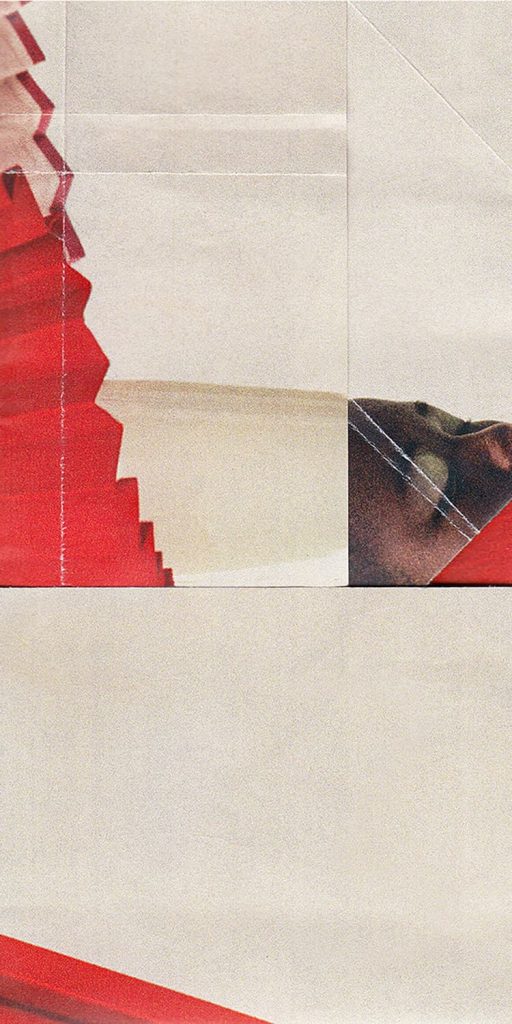

AB – love the term “Korigami,” which you used to describe your process of folding paper to create juxtapositions of different elements within advertisements. How did this process begin? Can you describe how you develop variations of each initial piece to create families of work?

EB –“Korigami” is a mashup word I coined for my process, blending elements of ‘collage’ and ‘origami’. The ‘k’ is for the cool kids. The simplest way to explain it is that I work with a single magazine page, folding it instead of cutting it up, while incorporating one or both sides of the page in the final piece. Each time a composition emerges from the folding, I scan it. I then repeat the same process until the material itself is completely deteriorated. In college, I primarily created traditional surrealist cut-and-paste collages. However, after watching the PBS origami documentary Between the Folds, I felt that incorporating some origami techniques into my collage experiments would help me develop my own vocabulary in the medium.

AB –Your artistic process seems to begin with a response to both the visual characteristics and the physical nature of your source materials, transitioning seamlessly between the physical and digital realms thereafter. Could you elaborate on how you navigate this transition, and how the physical aspects of a final piece integrate both printed and physical elements?

EB –When I first started making korigamis, my main focus was the image itself. I’m very selective about the images I use, and I keep as few sources as possible in the studio.

The embrace of materiality came during the folding process. You can’t escape the creases that form from earlier attempts when working with korigamis. The interesting thing is that the lines left by creases were just as captivating as the compositions themselves. They become even more intriguing once scanned. The digitization of materiality adds a layer of illusion to the final work that I find captivating. It also exposes the printing processes embedded in the original images, which I believe adds more meaning to the whole.

I think having a digital layer of distance between myself and the final piece is second nature. Everything else in my day-to-day life has a digital layer. Why wouldn’t my work be the same?

AB –As you continuously explore diverse source materials, how do you determine when you’ve exhausted an image’s potential? How does the act of scanning contribute to your particular understanding and reinterpretation of these images?

EB –When it comes to magazines, the material itself deteriorates from folding. As for different sources, I believe I’m still in the process of determining that. The advantage of shooting in RAW format is the ability to work with large files. I can crop images to microscopic levels of abstraction.

I make an effort to keep up with the fashion seasons. Once a season concludes, I also conclude working with those images. This approach keeps me focused and enables me to produce more work efficiently, as I constantly operate within a specific timeframe. I believe the scanner is an undervalued and underused tool in the arts. Despite its current moment of popularity, especially with the rise of 3D scanning and the metaverse, its potential remains largely untapped. My exploration with the scanner involves bringing once digital images back to their digital environment after existing in the analog realm. The transitional nature of this migration, the similar but not exact replication of images, the nuances, and the “realm-layering” are all aspects I’m interested in exploring. The scanner functions as an efficient yet complex intermediary that is essential to the concepts I’m exploring in this medium.

AB –Lastly, what projects or ideas are you currently exploring in your artistic practice?

EB –Expanding my wheat-pasting vocabulary has been crucial to me, and shooting posters in the street is the latest trend I’ve been pursuing. Speaking of grids, I’ve developed an interest in tiles, tiling, and home construction as forms of performance art. Although these ideas are still quite new, the concept of using advertising as construction materials emerged from my exploration of imagery and repeated tiling. Eventually, I plan to further explore the theme of repetition by delving into video and GIFs.