Composer and visual artist Julián Galay moves between sound, image, and performance to explore the shifting territories of perception and memory. His work resists easy categorization, favoring a poetic and sensory approach that invites reflection and presence. In this conversation, Galay shares insights into his process, the role of intuition, and the subtle, often invisible forces that shape his practice.

TWS – What’s the first thing you’d like people to know about you?

JG – I was born in Buenos Aires in 1988. I’ve been living in Berlin for the last five years. I describe myself as an undisciplined composer — a bit of a joke, but kind of serious too. I started with music and sound, but more than a decade ago I expanded into words and images, and since then, I’ve been making books, films, exhibitions, performances, and concerts. I think that’s a decent intro to who I try to be.

TWS – When you look at the way you describe your projects, words like: lecture-performance, concert, radio opera, installation, book, film, soundwalk, record, video installation appear. What kind of themes are you exploring through such a wide variety of formats?

JG –Since I was a kid, I had problems with disciplines. I wanted to be a visual artist when I was a kid, but I was so demanding of myself that music became a kind of escape — a way to relieve the pressure. I’ve also been writing forever, but that was something so transparent to me that I didn’t even consider it. Part of this comes from attending a public art workshop in Buenos Aires, which was more important to me than elementary or high school. There, we did everything: theater, literature, music, painting. I joined when I was still in primary school, and it just felt natural to think and create through all these different filters.

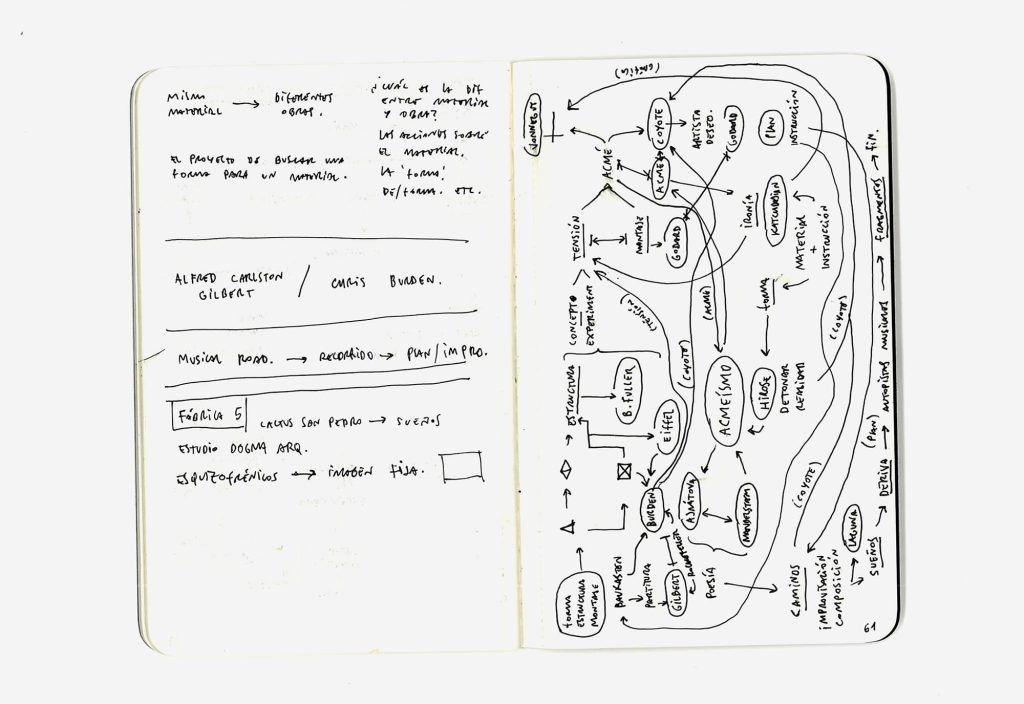

So, when it comes to working across disciplines, for me it was more of a release than an expansion — a process of being honest with what I felt my body of work was asking for. I imagine my body of work as a kind of entity that I’m trying to get to know and understand. Each piece, regardless of its form or medium, is a way of observing or listening to that entity from a different angle — revealing new details, shadows, parts of that larger whole.

In terms of the themes that run through my work, a few years ago I realized I’m interested in working within the space between perception and memory. I’m drawn to what happens between a viewer/listener and the object, the piece itself. That in-between might be listening, reading, looking — but it’s everything that’s triggered in perception, and also tied to memory. Once I understood that this was the space I wanted to work in, if an idea needed images, I’d work with images; if it needed only sound, then sound it was. The disciplines became more like a way to access or listen to that “entity” that is my body of work — and to follow what it was asking for.

I’m interested in working within the space between perception and memory (…) Once I understood that this was the space I wanted to work in, if an idea needed images, I’d work with images; if it needed only sound, then sound it was.

There’s something unique about creative processes — or maybe just about growing as a human — in how the present reshapes the way we understand the past. Like a friend of mine says: “No one knows the past that’s waiting for them,” because the past keeps getting redefined by the present. For example, in January I found some old floppy disks at my mom’s place, with stories I wrote in 1997, 1998, 1999. Sadly I couldn’t open them, but the titles alone were amazing — they showed I was already working with the same words, ideas and obsessions that now appear in a book I’ll be publishing soon. I wasn’t conscious of that connection before. Maybe if I hadn’t written the book, I wouldn’t have noticed the link. But now, with hindsight, I can say: “Wow, I was already on this track at 9 years old.” That kind of self-exploration is fun.

TWS – Does working across so many different disciplines make you feel like a visitor exploring new territories? Does it give you a sense of freedom, not being so tied to the “rules” of each field?

JG –Yes, absolutely. I studied really demanding and specialist disciplines — like contemporary classical music — with a long history and amazing teachers, but also with a heavy load of 19th-century baggage: meritocracy, suffering, pain… the usual with classical music training. Even as a kid, I started to suspect that I wasn’t comfortable with the idea of being a specialist. When I started saying that I worked in an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary way, I realized it was often looked down on — people might think you’re a fraud. Friends from the art world or science world would tell me, “Stop doing everything.” But I found something very appealing in the idea of the dilettante — a place where I started to feel comfortable, similar to the position of a foreigner: it can be hard sometimes, but it also comes with certain freedoms. Moving away from that place of authority or expertise gave me a position that I personally find much more interesting for making art.

Sometimes I find it contradictory that, in some of these hyper-specialized art scenes, artists present themselves as rebels against the status quo — but in practice, they’re at the service of institutions and power. It’s complex and full of contradictions. I’m interested in engaging with institutions, but stepping away from that kind of servitude gave me an exit from something that was bothering me: works that seek freedom on one hand, and on the other, exist entirely at the service of institutions or disciplines — which ends up being very disciplinary in itself.

What attracts me is the search. It makes sense as long as I feel like I’m moving forward in that direction. It’s not the most economically profitable path, nor the most practical one to be part of the “art world.” Art moves through networks and specializations, and it would be arrogant to think you could enter all of them. But as always, when you gain something, you lose something — and vice versa. That’s where decisions live.

I’m really happy to have the chance to make the work I do, and generally, I feel very well accompanied. Making work is also a way of finding accomplices, friends, kindred spirits — and of connecting with people from different cultures, countries, languages, with whom, through the work, a kind of telepathic or spiritual friendship happens. That’s incredible — and it’s not tied to the limits imposed by the market, or institutions, or whoever decides what music is, what cinema is, what literature is, etc.

Related to this, I’ve always been fascinated by reading books written by photographers, watching films made by composers, or admiring visual art made by architects. That fascinated me in a very natural way. You’re just drawn to what moves you, and you start emulating or having a dialogue with what excites you. In that sense, I’m not inventing anything new — I’m just trying to enter into conversation with the things that attract me.

Making work is also a way of finding accomplices, friends, kindred spirits — and of connecting with people from different cultures, countries, languages, with whom, through the work, a kind of telepathic or spiritual friendship happens.

TWS – There’s a certain freedom in daring to work outside of one’s own field of expertise…

JG –Yes, but at the same time — just to balance what I’ve said — I want to talk about the other side of the coin. I’m fascinated by pedagogy and learning spaces. I’ve been teaching a workshop on creative processes for many years, and I’ve taught at the university level too. And even though I practice this kind of openness, I also think it’s very important to learn to do something — and to do it well. Specialization itself isn’t the problem. When a photographer writes a book, and I find it inspiring, it’s often because they’ve been working in photography for 15 years, developing their technique — and that practice (which is almost ritualistic) gives them a tool to get to know themselves. I think it’s important that someone becomes skilled in something.

And it’s not just art that’s like mine that I admire — often it’s the opposite. I’m fascinated by people who have been writing since they were two and only write, or by those who paint yellow paintings their whole lives. That kind of devotion really impresses me. I believe in personal practice, in working with commitment and intensity — that’s fundamental.

There’s a contradiction in all of this, and it’s not simple for me. I also come across artists who say things like, “I make music, but I don’t care about anything else — I hate reading, I don’t want to learn, I don’t want to get contaminated by ideas.” I don’t agree with that either. It’s complex. I think it’s important to learn how to do something — and from there, you can begin to do other things.

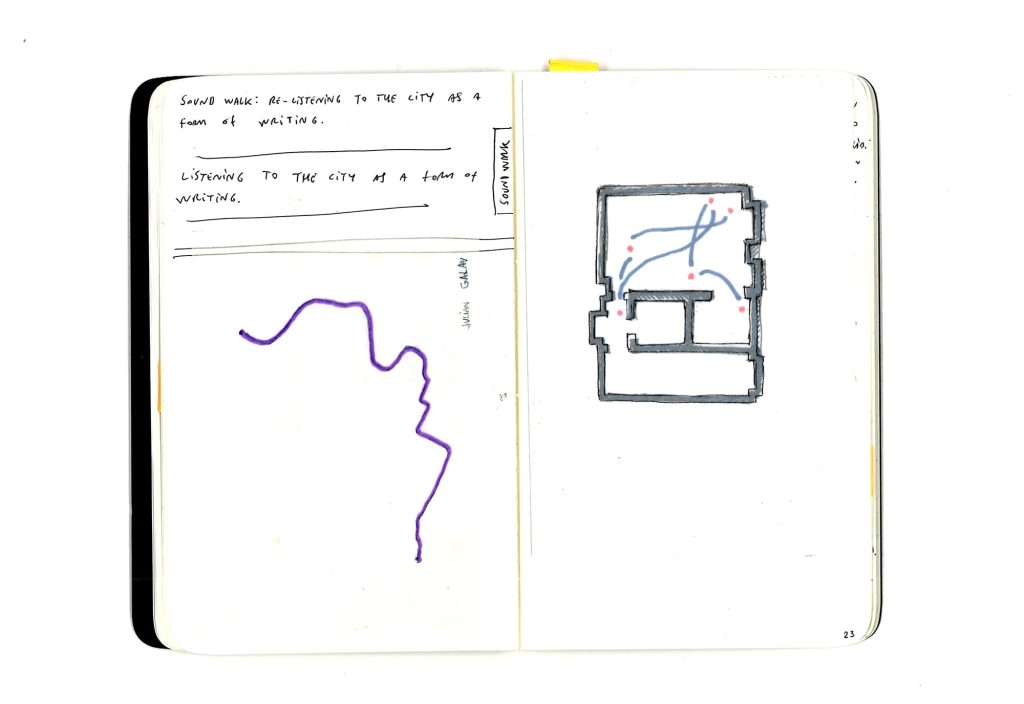

TWS – The titles of your works –PHANTOMS (Opera, Telepathy and Friendship); MIMESIS (Animal Dreams and Tuning Forks); Listening to the City as a Form of Writing –suggest a fascination with the invisible. Are you trying to reveal something that’s hidden but also part of everyday life?

JG – Absolutely. Titles are incredibly important to me. Very often, a piece starts with just a word, and then I begin to dig into the reason for that word. Sometimes it adds a conceptual foundation to the work. If I’m working on a sound-only piece, the title helps me juxtapose those abstract sounds with something else—it gives them a setting, a kind of meaning. The title holds everything up, and whatever appears in the work plays against that word—like a collage.

I’m very interested in things that can’t be perceived—what can’t be seen or heard—the ineffable, the unnameable. I’m drawn to spaces like music, dreams, or mathematics (even though I’m no mathematician), where language moves beyond the everyday. Animals, too, have practices that develop beyond words that I find incredibly fascinating. Working with animals—beings that don’t “speak” in the way we do—makes me think that they do communicate in some way, metaphorically or not. There’s something there that’s connected to the hidden and the mysterious.

Lately, I´ve been playing with two words around the natural: supernatural and postnatural. I’m interested in the paranormal—not in the sensational sense, but in supernatural and paranormal just beyond what we consider normal. Things we don’t fully understand but that are part of our everyday surroundings. Something as simple as a reflection in a window. I get excited about the ordinary, the small unnoticed things. We often associate the paranormal with the extraordinary, but it can also live in the realm of the possible.

Science has always fascinated me—partly thanks to my family background. My family is split between science and architecture/engineering, which I think explains a certain rigor in my approach. But I’m also attracted to so-called “lowbrow” or discredited sources of knowledge, like ghost stories or paranormal phenomena. Many of my ideas come from Instagram reels, dubious information sources, or bizarre academic researches. That kind of information—raw and not necessarily valuable in itself—can spark a montage, a composition.

There’s a filtering process involved: trying to distill that sea of content and reposition it in a new context. That’s what art often does. You take something seen as “trash”—an object floating in a river, for instance—put it inside a glass case, and suddenly it reveals a hidden beauty.

I’m also very interested in the unconscious—the unconscious of spaces, of institutions, of cities. That is, everything that’s present but not intentional: advertisements, digital junk on social media, literal trash I find on the street (which in Germany is quite something, especially from the perspective of a foreigner who sees everything with a kind of detachment). All of that might represent the unconscious—the things that are said without being spoken. I love taking those things and reclaiming them, using them in some way.

Titles are incredibly important to me. Very often, a piece starts with just a word, and then I begin to dig into the reason for that word.

TWS – You mentioned that titles often mark the beginning of a project. Since you work across so many media, what’s your creative process like? How does a piece take shape?

JG –For quite a while now, my process usually begins with an obsession. I fixate on a theme and start researching it deeply. For instance, for the past six or seven years, I’ve been immersed in studying animals and their relationship to cities, institutions, and language. I go deep into it—I interview scientists, visit natural history museums, take photos, read books, watch documentaries, and even scroll through random animal-related content on Instagram. I fill notebooks with anything that grabs my attention.

Eventually, I collect so much material that it starts to push back—it demands to become something. With the animal theme, for instance, I feel like I’m about to close a chapter. In July, a major cycle ends with the premiere of my first feature-length documentary, Los Cruces, made with the collective Antes Muerto Cine. After six or seven years, the film will finally premiere at the FID in Marseille, one of my favorite festivals, which will be a natural conclusion to this research and, at the same time, for sure will open new conversations on the subject.. And while working on the film—because the process was so long and intense—other pieces started to emerge, like EPs or singles a musician puts out while working on an album.

The film is centered in Argentina, but along the way I gathered tons of fascinating material connected to Europe. So when MACBA (Museu d´Art Contemporani de Barcelona) together with the Institute of Postnatural Studies commissioned me to create a talk in response to the of Cripsis -something similar to mimesis- in the work of Daniel Steegmann Mangrané, it was perfect timing. I had six years’ worth of notes that didn’t fit in the film but were still very relevant. That’s how MIMESIS (Animals, Dreams and Tuning forks) came to be.

I really enjoy when pieces contaminate each other. I love leaving little clues throughout my work. So in Mimesis, you’ll find scenes from the film. And Mimesis in turn influenced the film—something I wrote for the talk ended up in the movie. At the same time, a book of my diaries from the film’s production was published. Everything is part of the same investigation. The words go into the book, the music I was making in Berlin using tuning forks became the film’s soundtrack. These pieces naturally bleed into each other. I don’t just accept it—I really enjoy it. I like bringing them closer together to see how they interact. The book features a still from the film. I love those intersections.

It’s been years since I’ve faced a “blank page” moment because I work in “slow-motion multitasking”—I’m usually writing a book, making a film, and composing a concert all at once. I enjoy long processes—like spending six years making a film.

The book PHANTOMS (Opera, Telepathy and Friendship) also had multiple stages. It began in 2020 with analog photos. Then I made a radiopera using only WhatsApp voice notes. Later, I was invited to create something for an installation at CASo (Centro de Arte Sonoro), so I thought of a performative lecture for the opening. An editor, Martín Bollati, saw that talk and said: “This is a book.” And so the sound piece, the performative lecture, the installation, the book, and the photographs all emerged from the same core, edited as separate things but ultimately stemming from the same research—though I say that word lightly. A friend of mine, who’s an agronomist and a good scientist, used to laugh at me when I said something I pulled from the trash was “for my research.” In the end, we all invent our own games.

TWS – Please tell me about the performative lecture you mentioned.

It’s something I’m really happy with—something that took me years to distill. It emerged almost by accident, and it had to do with finding a portable way to make work.

At one point in my career, I received a commission from CCK (Centro Cultural Kirchner in Buenos Aires), which was still under construction. The commission didn’t pan out—due to reasons unrelated to me—but I approached the director and producer at the time and pitched a wild idea: to build scale models of the important buildings in my life. It was a total leap of faith, and I’ll always be grateful—he said yes. He gave me a premiere date. Suddenly, ten years ago, I had to create this multidisciplinary piece that was absolutely nuts, and I just dove in.

That led to other opportunities in Buenos Aires—working on large-scale pieces for venues like Teatro Colón, Teatro San Martín, and various festivals. These were complex stage productions involving teams of 30 people, live ensembles, scale models filmed and projected in real time, and a narrator. They were incredibly elaborate and marked the first time I combined music composition with text and image.

When I moved to Europe in 2020, I hoped to continue along those lines, but of course I had no connections or network. I realized how hard it would be to keep making these massive, ambitious pieces—part of their appeal was that they felt impossible.

Then came two years of lockdown due to the pandemic—on top of being in a new country, with no contacts and not speaking the local language. That forced a shift toward writing and filmmaking—natural consequences of isolation. With no performances, no live shows, no stage projects, I focused on working with sounds, words and images in portable formats.

When I finally returned to performing live, the idea of a performative lecture came up. It’s just me and my backpack—very portable and, in a way, economical. It’s a format where I can read texts, play instruments, perform live sound, and project images—moving or still. It’s a sort of live concert-film. I realized it connects directly to those huge earlier productions, but now in a distilled, simplified format.

As you mentioned with Fantasmas or Mimesis, I’m very interested in escaping the academic, overly serious tone. But the topics that attract me are often complex. The performative lectures helped me find a device that allowed for lightness—and even something that’s hard for me: humor. I feel like the contemporary music world can be very solemn, which I try to avoid, even if my themes don’t always help. But performing, being present, using my voice—those things create closeness, a kind of relief, something grounded in everyday life.

For me, it’s simple: a talk with sounds and images. But it was a revelation. Fantasmas was the first one, then came Mimesis. I’ve presented Mimesis in Barcelona (MACBA), Mexico City (MUAC), and Buenos Aires (Fundación Andreani). Suddenly, this format allows me to travel with my work. I used to spend two years making massive productions that would be shown for a single weekend. That’s crazy in terms of emotional and resource economy—a total waste. Now, I can spend years writing and end up with a piece I can travel with, perform, and present without depending on anyone.

Performative lectures are a perfect format for me—they function as works-in-progress, ways to sketch out the early stages of a piece. I’m currently developing more. A new one premieres in July, and another is planned for October—if all goes well, it will bring together obsessions I’ve carried for more than a decade, maybe my entire life. That October lecture is about my grandfather, the birth of modern science in Argentina, and the origins of electronic music in the Americas. The lecture is a small format—a first step.

Right now, I think it might evolve into a film… although if the same thing happens as with the previous film, that may take more than five years! It’s a way to manage anxiety and find collaborators. When you give a talk about, say, nuclear fission, people start showing up—an anthropologist who works on the subject, an influencer who advocates for atomic energy, someone’s grandson… It’s amazing to circulate ideas and see how they collide with others. I’ve found that this enriches the project and deepens the creative process by giving the work a space to be shared mid-flight.

TWS – In your bio, you mention that personal diaries, dreams, and archives are the raw materials you process to create your work. Tell me more about your relationship with these elements—and is there any other raw material you’re currently interested in?

JG –Dreams are something universal—something many people are drawn to. My relationship with dreams began in childhood with one of my best friends. We had this game: he’d come over to my house, and I’d tell him my dreams from the night before. We were just kids in elementary school. I think that game, sustained over time and with a certain regularity, gave me a practice in storytelling. In telling a dream, you also create it—the dream itself shifts and changes. In a way, that was my first diary. Collecting dreams led me to remember them more vividly, and as a kid or teenager, I started keeping a dream journal. So it became a natural interest.

Later, when I began making work, I became fascinated by the idea of dreams as an automatic machine generating meaning, language, images, sound… something that escapes conscious control, an internal factory at work. Everyone has one. I’d think: how many dreams are generated each day around the world? I like the idea of a dream as a work of art.

One theory about how dreams are generated really fascinates me: that they arise from the collision of memory and perception—two realms I’m deeply interested in. While you sleep, everything happening around you (sounds, temperature, smells) becomes the raw material of the dream as it collides with memory—whether from the previous day or from years ago. I realized that this collision between perception and memory—so similar to the way dreams work—interested me as a creative mechanism.

That’s how I began building dream collections. I asked friends and family to send me their dreams, and I started creating obsessive lists of recurring words and objects. Eventually, I naturally started using my own dreams as raw material—for ideas, sounds, etc. I was also blown away when I learned that animals dream—spiders, parrots, monkeys… That really opened something up for me because it de-centers the human as the main subject.

I also wanted to move away from certain artistic practices traditionally tied to dreams, like surrealism or Freudian psychoanalysis. While I find them fascinating, I feel dreams often get funneled into very specific interpretations. I wanted to try a different path—to find my own devices for working with something so universal and everyday.

Archives are also something I’m very drawn to. For me, documents—whether bureaucratic or from a film archive—are like institutional dreams, their unconscious. Think of a scientific institution recording a bird’s movements 24 hours a day, or capturing its song. All that accumulated information is involuntary, and it just sits there. My approach to archives, whether my own or others’, is very similar to how I treat dreams: I take something that interests me and generate juxtapositions—montage.

In that sense, my practice is closely related to collage, even if I never called it that. When I write, I work heavily with quotations, “stealing” and rewriting things that fascinate me. The same goes for images and sound. When I record a crow, I’m “amplifying” reality—cutting out a piece that I didn’t invent, but rather stole or collected. I’ll pick up a card from the trash, record a bird’s call, jot down a friend’s dream, lift a quote from Vila-Matas… I gather, and then I compose—shaping it into something. That’s where it connects to your interest in collage.

Then there are my personal diaries… Just today I was writing about my favorite book: La novela luminosa by Mario Levrero. It’s like a Bible without religion to me. I read it twelve years ago and it was like Kafka’s “axe for the frozen sea inside us.” Levrero helped me realize I was drawn to memory and perception. I think he—and certain life experiences—made me understand that sound alone wasn’t enough, that I had to open myself to words and images.

Ever since reading La novela luminosa, I’ve kept a daily journal. I used to write diaries before, but since then, I do it religiously—every single day. During manic periods, like during the pandemic, it intensified and I’d write for two or three hours a day. Thankfully that’s no longer the case. But that daily habit generates a kind of “dump”—the writing is illegible, embarrassing. I wouldn’t want anyone to read it. I talk about whether it’s raining or if lunch made me feel sick. But then, as with dreams or archives, I lose focus or drift off and suddenly something interesting appears. I don’t even notice it at the time. Later, when I’m working on a theme—say, islands—I’ll go through a document of 25,000 pages from 13 years of writing and I’ll find these unexpected ideas buried in obsessive, excessive language.

Again, the act of writing disappears—I’m simply editing words I wrote at another moment. I work with my own diaries, my dreams, and with the dreams, diaries, objects, or archives of others. I approach them the same way. Of course, I love rewriting and editing. I truly enjoy it. Once I’ve nailed down the core of what I want to express—the idea, the emotion—I start rewriting. I don’t leave the original journal entry untouched; I’m not interested in that kind of fidelity. That’s when writing becomes a craft, whether musical, audiovisual, or literary—and I love that process. I love working with a text—cutting, changing words, printing it out and rewriting it. It’s like editing a film or composing music. These are different moments. One is recollection, the other is composing. There’s almost never a “blank page” moment. If I write what comes to mind every day, that moment of “what now?” doesn’t exist. For me, composing is an act of distillation—of filtering, of removing, removing, removing.

I have more than enough material. In the worst sense of the word, it’s like “garbage.” So making a piece usually involves subtracting, climbing that mountain of material to see if there’s something worth keeping, rather than adding new things.

…my practice is closely related to collage, even if I never called it that. When I write, I work heavily with quotations, “stealing” and rewriting things that fascinate me. The same goes for images and sound. (…) I’ll pick up a card from the trash, record a bird’s call, jot down a friend’s dream, lift a quote from Vila-Matas… I gather, and then I compose—shaping it into something.

TWS – Another idea that comes to mind when listening to you is “collecting”. Is the act of collecting something that resonates with you?

JG –Absolutely. I’ve had to wrestle with my obsession with collecting—there’s something potentially violent about wanting to accumulate everything. I think it’s something I inherited. Paraphrasing César Aira (I can’t remember the exact quote), collecting is a way of suspending death. There’s an obsession in collecting that ties into that idea. In my childhood home there were all kinds of “absurd” collections—we weren’t wealthy or anything, but there were bottles, things hanging from the walls, instruments, paintings. My parents always loved art—we had original works, records, books. As a kid I collected whatever I could: bottle caps, magnets, erasers. That impulse evolved over time. At one point I collected records. I still have a huge collection. Thankfully I stopped because I never had money, and when I started traveling and moving, I realized it was madness. I made a promise to myself not to buy more records.

Today, my work has become the channel for that impulse. I mostly collect things for my work—conceptual things that don’t take up space or cost money. My only “problem area” is books—I spend more than I should on them. I read on paper. I have a fetish—I can’t deal with digital. That urge to collect now lives on in books and information. I have an “atlas” of quotes, a folder full of images. It’s all more digital now, so it’s less problematic—I’m not turning into a hoarder living in a house you can’t walk through. I’m far from that. I like things simple and clean. But I can see how I could’ve easily gone down that road.

TWS – Just out of curiosity, tell me about your record collection…

JG –My childhood home was full of music. My brother worked at Tower Records—he handled the classical section—and had a rock band. My sister listened to really different, really good stuff—Björk, Bowie. My dad listened to everything—he sang in contemporary choirs, played clarinet and saxophone. We had a piano at home—I started lessons when I was a kid. It was an eclectic record library: jazz, classical, rock, hip hop, folk… There were Beethoven string quartets alongside albums that were considered in bad taste at the time. Thankfully, thanks to my parents, I never had cultural prejudices or snobbery about music.

I remember being obsessed with bands like System of a Down or Radiohead as a kid. My dad, with all his musical knowledge (even though he wasn’t a professional musician), would hear them in the background and say, “This is amazing—what is this?” At 12 or 13, I was shocked that my dad, someone who listened to Mozart, liked Radiohead. But later I realized—he just recognized it as great music. I’m grateful I didn’t grow up with that filter. It might sound obvious now, but even in art school, you can still run into the ghost of high vs. low culture—thinking a Joyce novel is more valuable than a comic book. That wasn’t the case in my home.

TWS – You once said that sharing your projects allows you to find allies—people to share ideas with, to exchange thoughts and impressions. You run a music label and a publishing imprint. Is collaboration a fundamental part of your practice or creative identity?

JG –Just like dreams, archives, trash, and personal diaries are places I turn to for material, conversation is also essential to me. That’s why I really appreciate this chat—it’s formative for me, I learn from it. I was lucky to play for 13 or 14 years with a group in Buenos Aires. We started young, back in high school. It was called Ensamble Chancho Cuerda. We recorded four albums, played live a lot, toured, won awards. The music we made, which I still love, has nothing to do with what I do today—it was more rooted in Latin American traditions. We performed with musicians I deeply admire—Liliana Herrero, Fattoruso, Leo Maslíah… I’m really grateful for those experiences. From that time, I learned technique—how to play bass, how to play in a group—how to travel and connect with different realities.

I was also lucky to start being interviewed at a young age. In my last year of high school, I was already doing interviews for the band. That’s when I realized the interview could be a powerful way to get to know yourself—and others. I started conducting my own interviews—not as a journalist, but just because I was excited to ask questions and understand other people’s creative processes. I began to see that conversation—whether in friendship, a couple, or family—is a huge source of nourishment. I’m surrounded by very generous people who talk with me, and I pull out my notebook and take notes—I’m constantly “stealing” what they say. Luckily, they enjoy it, and I always try to be transparent about it—hence all the acknowledgements in my work.

But I find something very motivating in this: often, research or making work comes as an excuse to have a conversation — not the other way around. I don’t talk to get ideas for works; I make works so I can talk. The radiopera made from 47 WhatsApp voice notes came about during the pandemic. I was in Germany, missing people in Argentina, and I invented a project as a way to have conversations around specific themes. I told 40 friends: “I want to talk with you about masks/silence/light — send me a voice note.” And so I created a kind of correspondence. I made the piece, which stayed “hidden” on my computer for two years. If the CASo hadn’t invited me to share it, I probably never would have. It was simply an excuse to talk.

In that sense, collaborations are essential. The film that’s about to be released was made with the Buenos Aires-based collective Antes Muerto Cine, with whom I’ve been working for over a decade. The group is made up of many of my closest friends. I collaborate as a sound designer and director. Making films with them is a kind of friendship adventure — an excuse to shoot, to go into an abandoned village, to film, record, and talk. The credits say I directed, Tatiana Mazú was behind the camera, Manuel Embalse edited, and Florencia Azorín and Joaquín Maito produced, just to mention some of the crew. All of that is true. But because of our friendship and trust, everyone has a say in everything. I learned that from Ensamble Chancho Cuerda, which was my school, my human and artistic “university.” There were seven of us and we all composed, arranged, produced, organized — a kind of artistic anarchist socialism. That experience shaped me. Radio La Tribu in Buenos Aires was also key. Years ago, with friends, we started contemporary music orchestras that worked as collectives (something quite rare), doing concerts in public spaces, on the streets, in unusual settings.

I’ve always been drawn to friendship and collective work. It’s connected to how I want to live, and that seeps into the work — again, it seems to happen the other way around. Collaborations are very important to me. Creating work is also a way to have indirect conversations with those I care about. I think it was Virginia Woolf who said that knowing how to write means knowing who you’re writing to — even if it’s imaginary (someone who passed away, another writer, your childhood cat…). It might not be conscious, but there seems to be an impulse or desire to communicate something — not necessarily a verbal message, but an experience, emotion, or idea. In that sense, collaboration is everything. In any creative process, I always count on my friends, to whom I send drafts of short films, texts, sounds. I’m deeply grateful for that.

TWS – Dare to recommend two or three pieces online that represent who you are today as a creator?

JG –That’s a super tough question for me. It always is — whether someone asks me or when a grant application wants me to show my work in one or two links. It’s the “B-side” of working with this “monster” and its details. I think it happens to a lot of artists: I tend to recommend whatever I’ve made most recently.

There’s also something else that interests me. A lot of my work is performative: playing tuning forks, my duo with Kevin Sommer (a Swiss musician and clarinetist I collaborate with to explore architectural resonance), performative lectures. It’s art that happens live. I’ve always resisted putting videos or recordings of these works online because I feel it takes away something essential. I’m deeply interested in working with architecture, space, resonance, and acoustics — and all of that disappears on a computer.

On the one hand, I find that attractive — it maintains a certain mystery. On the other, I’m completely burnt out and oversaturated with the virtual. For me, having a physical space to meet is a small act of resistance. I play tuning forks in a small room, maybe for six people, but there’s that ritual of gathering, of something happening there and only there. I work with improvisation, and it stays in the moment. I try to let go of the obsession with documenting and sharing everything.

In that sense, what circulates the most are the books. El libro de las fuerzas, published three years ago in Barcelona by Temporal Editora, distills some of my obsessions into words —and next month, a kind of involuntary continuation will be published: El libro de las sombras. I invite people to visit my website — it’s like a catalogue — and to “peek” in and see if something resonates. Ideally, keep an eye out in case I pass through your area with a talk, a film, or a concert — and we meet, and that encounter can happen.

Learn more about Julián Galay visit his website and Instagram.