All photos by Todd Bartel, unless otherwise noted.

After his residency at the Salvatore Meo Foundation, covered in Part 1 of this interview (link), Todd Bartel’s As Is assemblages and interlocking collages were exhibited alongside Salvatore Meo’s assemblages, collages, and drawings at Sala 1 in March 2024.

The curator who introduced Todd to the art of Salvatore Meo, Kelli Bodle, (Boca Raton Museum of Art, Boca Raton, FL) was invited by Mary Angela Scroth—the Artistic Director of Sala 1, and the founder and President of the Fondazione Salvatore Meo—to write an essay for the exhibition. In her opening two paragraphs, Kelli Bodle celebrates Todd’s approach to his work:

One is impressed most with the meticulous care that Todd Bartel puts into the technique and concept of his collages. Over the entirety of his production, there is a precision — be it in terms of his intricate cutting process or the exact definition of a word, such as “landscape.” Bartel’s dedication to following an idea down to the very seed of its beginning reveals some of the most semiotically important work in collage today. The deeper one delves into his seemingly dissimilar images, the more universal the images become. What an image might mean prima facie, or even symbolically, is changed and imbued with new, more profound meaning, courtesy of Bartel’s thoughtful juxtapositions.

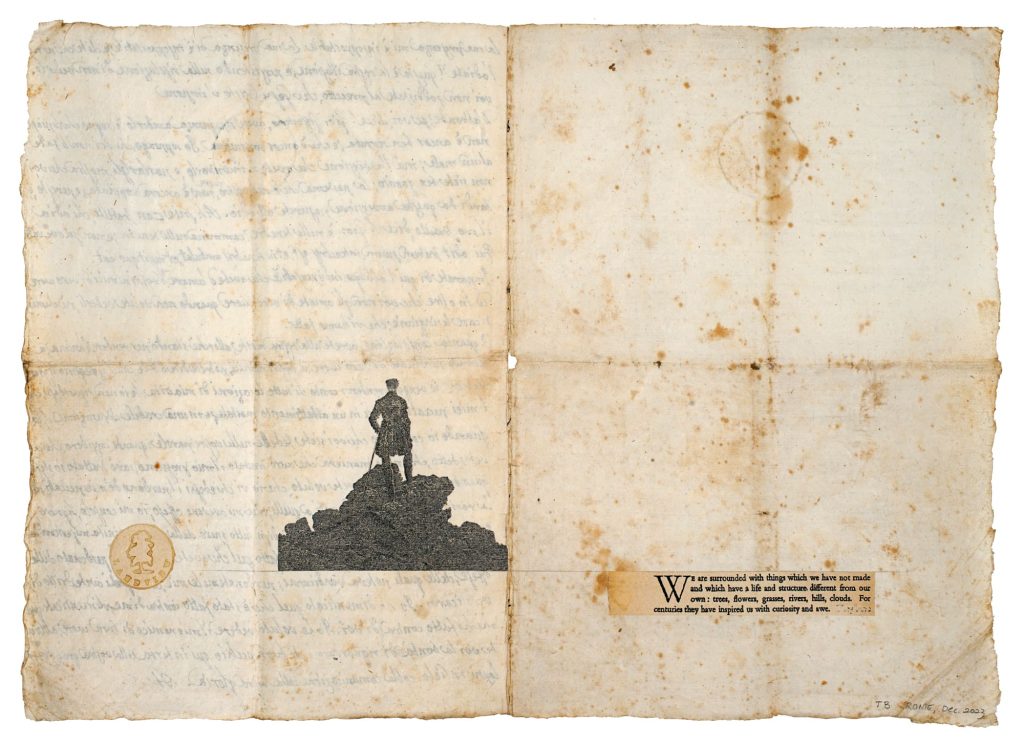

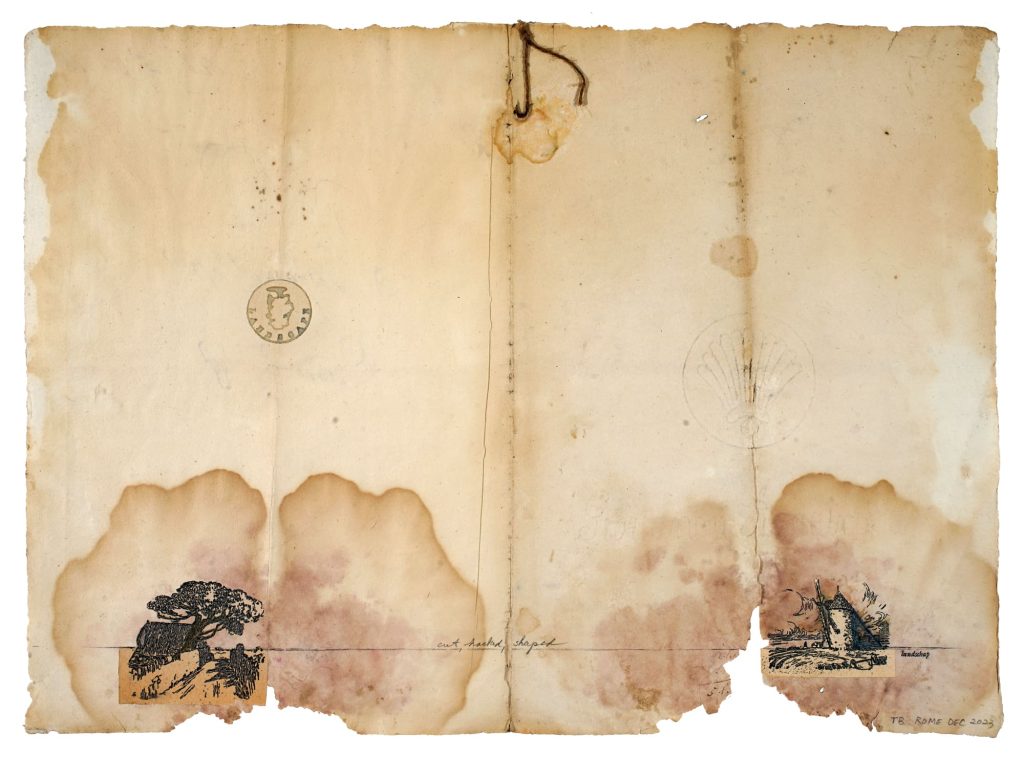

Interlocking collage, lemon juice print, pencil and xerographic transfers on 20-century end-page cuttings inset into 19th-century Italian letter, document repair tape. Text lower right: Kenneth Clarke, Landscape Into Art (1949), Icon Editions (HarperCollins), New York, revised edition, 1991, p. 1

“We are surrounded with things which we have not made and which have a life and structure different from our own: trees, flowers, grasses, rivers, hills, clouds. For centuries, they have inspired us with curiosity and awe.”

The As Is exhibition paired twenty-five works by the two artists (and a found object by Salvatore Meo) in an effort to shed light on their overlapping and divergent approaches to working with found materials. As Is celebrated material and process overlap between both artists while showcasing Todd’s dedication to eco-art.

AB –A major theme of your work is an investigation into how we relate to land and nature. Can you share more about the inspiration behind the As Is series created at the Meo Residency and how it relates to these themes through your broader body of work?

TB –I was thrilled when both curators, Mary Angela Schroth and Kelli Bodle, agreed to my exhibition title and concept for the show. Their endorsement meant that I did not have to completely reinvent myself as I developed a concept for my residency artwork. As we noted in the first half of this interview, the As Is concept works in celebratory ways as defined by shared affinities between my work and Meo’s in that we both honor things that withstand the ravages of time, and we both use similes in our practices.

However, there is also a sense of the phrase “as-is,” which means something is no longer in “good shape” or is “not pristine,” and thus, the phrase “as-is” has a cautionary overtone as well. It was the cautionary side of the phrase that allowed me to link up my concerns with landscape, ecology, and the Anthropocene era to my residency work. My work is quite different from Meo’s in the sense that I exclusively use the materials I find to explore my lifelong dedication to landscape history and ecology, and that is where our respective studio practices part ways. Once my proposed concept was approved, I thought I would simply apply my general approach to research, and I hoped I would find something compelling in Rome to galvanize my focus.

While I was entirely at the mercy of what I would ultimately collect and find to work with while in Rome, I knew ahead of time I wanted to at least reference a book I had recently obtained: Should Trees Have Standing: Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects, a 1972 book by Christopher Stone. I brought that book with me, among several others, and read it on my flight to Italy. Indeed, text from that reading would ultimately appear in two of my works. With that initially as my mindset, during my first few evenings in Rome, I worked on selecting and transcribing text from the books that I wanted to use to ready them for use in my collages. In the middle of doing that one evening, I received a verifying text message that shifted my overall focus in a much more acute way.

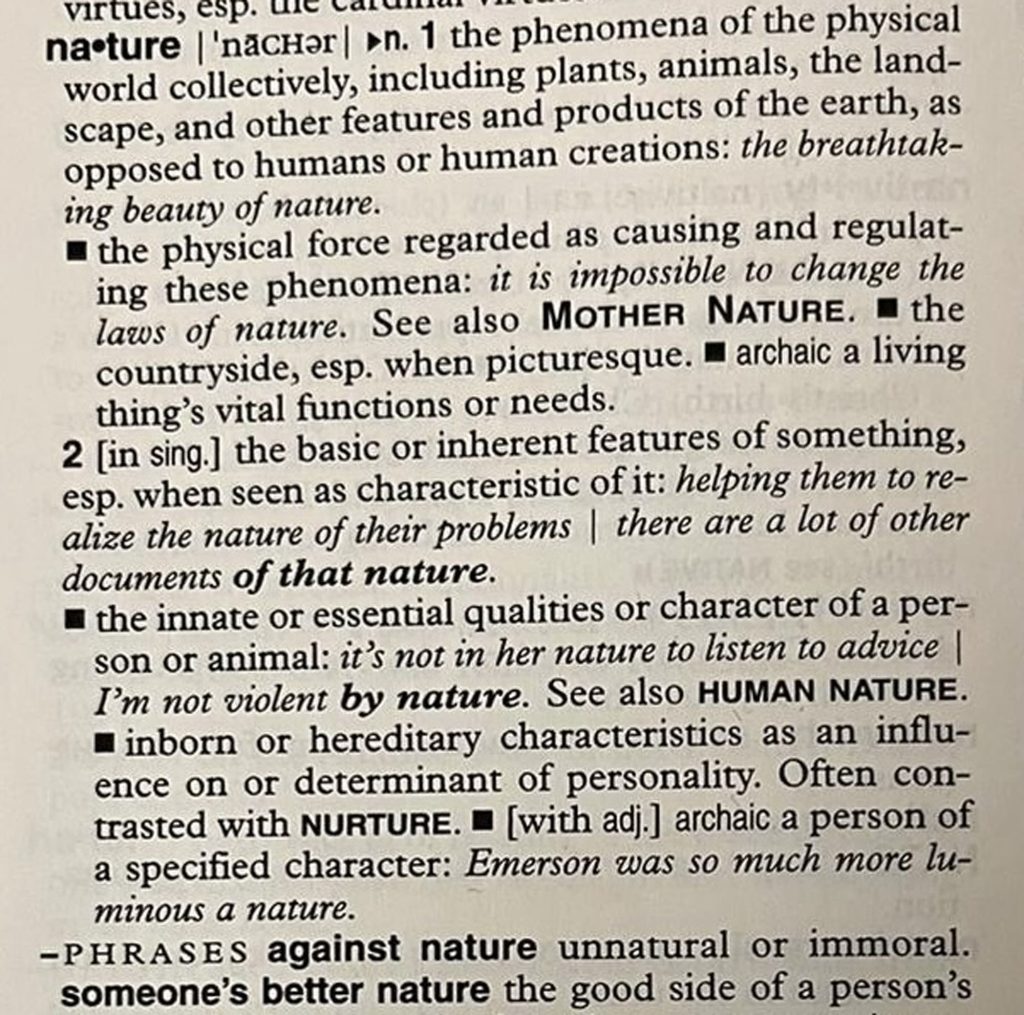

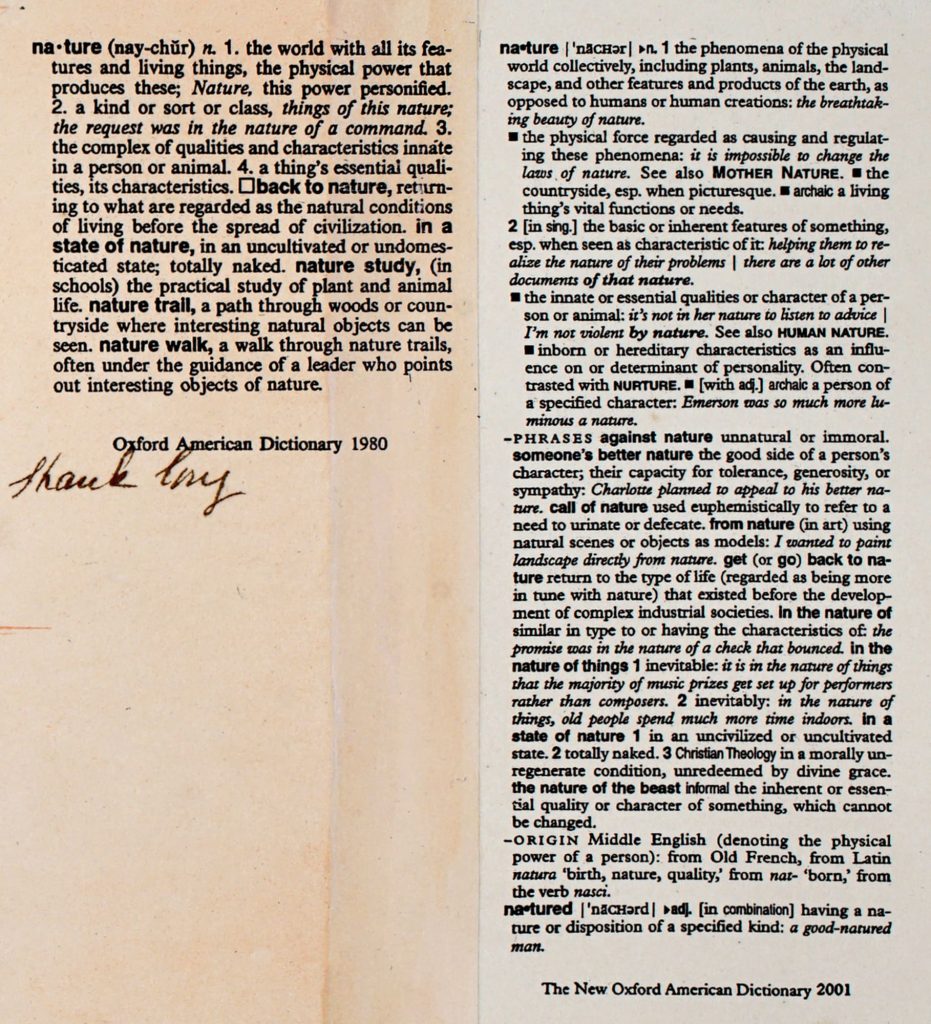

On that third night of my residency, my spouse of 35 years (and 1984-85 Rome studio mate), Talin Megherian, texted me that the copy I had ordered of the 2001 first edition of the New Oxford American Dictionary had finally arrived at home in Boston. I had hoped to bring it with me to Rome, but it didn’t arrive in time. Talin’s message and her subsequent photographs of the definition of “nature” and the dictionary’s title page catalyzed my creative activity in Rome.

With her verifying photographs, I finally had, in my (general) possession, the proof of the United States of America’s removal of “humans and human creations” from the definition of “nature.” I decided then and there that the subject of “nature” had to be my conceptual focus during the Salvatore Meo Foundation residency.

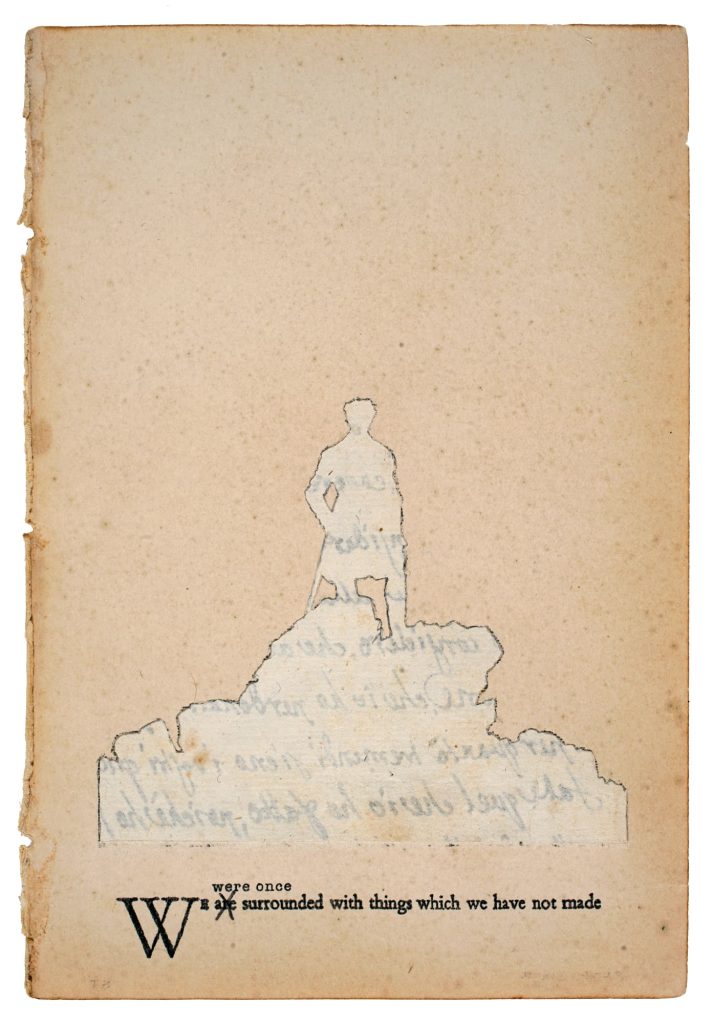

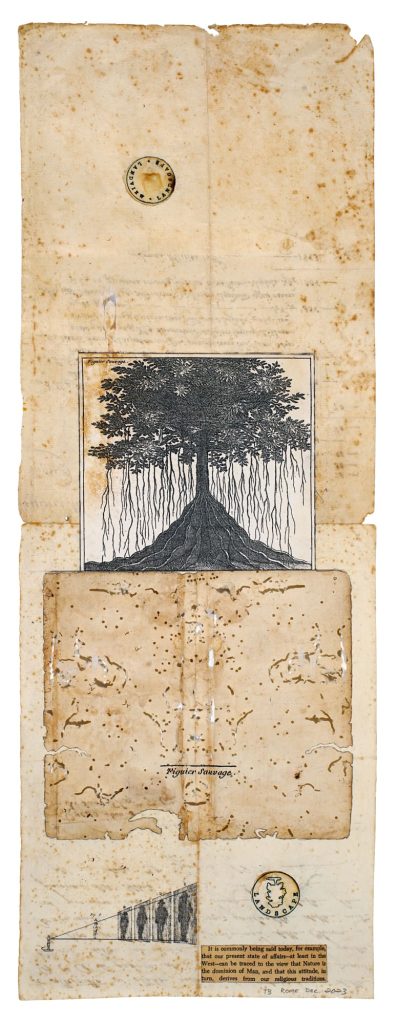

Interlocking collage, pencil, 19th-century Italian letter inset into 20-century end-page with xerographic transfer, document repair tape. Text at the bottom: Kenneth Clarke, Landscape Into Art (1949), Icon Editions (HarperCollins), New York, revised edition, 1991, p. 1

“We

AB –How do the As Is works connect to your experience and the works you made at Weir Farm? How do they differ?

TB –The work created at both residencies is generally rooted in my decades-long effort to understand the definitions of “nature” and “landscape” and how humanity has related to these since the dawn of The Agricultural Age. The difference is that the Landscape Vernacular series explores many other related ideas and the history of where they emanated, whereas the As Is series was centered on a concentrated body of work exclusively reflecting on “nature.”

Definition comparisons: Oxford American Dictionary (1980), The New Oxford American Dictionary (2001),

I initially thought the Meo Residency had the potential to be disconnected from the Landscape Vernacular series because Meo’s studio practice did not really focus on landscape-based ideas. Being able to bend my own interests towards Meo’s while retaining my passion was a welcome surprise.

The connection between the two residencies was the galvanizing acquisition of both dictionaries in the same calendar year. Together, these volumes document a crucial point in human history regarding the shift in the definition of the word “nature”—one volume includes humans and their creations in the definition, and the other volume excludes them. These publications are contemporary, with only twenty-one years separating their publication dates, with the most recent volume published in 2001. Like bookends, the Weir Farm residency was capped by the initial dictionary acquisition, and the onset of the Meo residency bookended the other. In the span of just under six months, I had obtained two dictionaries that linked Edenic expulsion to linguistic expulsion; I knew I had to do something about that. If the dictionary had arrived after my Rome residency had finished, I’m sure I would have done entirely different work.

Because of these dictionary acquisitions, I became more relaxed about my political voice entering my work when creating the As Is collages and assemblages. By contrast, in Landscape Vernacular collages, I let the voices of others and the things I juxtaposed them with do all the speaking.

Interlocking collage, lemon juice print, and xerographic transfers on 20-century endpaper cuttings inset into 19th-century Italian letter, pencil, document repair tape. Text insertion: The New Oxford American Dictionary, Ed. Elizabeth J. Jewell, Frank Abate, Oxford University Press, New York, 2001, p. 1140

“Na•ture | ˈnāCHǝr | >n. 1 the phenomena of the physical world collectively, including plants, animals, the landscape, and other features and products of the earth, as opposed to humans or human creations”

AB –In these works, you continue to explore how the words we use to define concepts deeply shape the way we think about the world around us. How has your exploration of dictionaries and the removal of “humans” from the definition of “nature” evolved in this new body of work?

TB –As we established in the first interview, I began my pursuit of physical dictionaries that demonstrate the expulsion of humans from nature in 2011, which, in fact, initiated my Landscape Vernacular series. At Weir Farm, I worked on the more complicated projects in that series because the time and the space allowed for that kind of focus. I was doing that work in anticipation of my then, upcoming show at Anna Maria College. During my Weir Farm residency, although I made the previously described dictionary discovery, I had not yet made anything in response to collecting the smoking-gun definitions of “nature.” That all changed while I was in Rome, necessarily so.

On the heels of having just arrived in Rome, Talin’s news meant that I had finally answered my query in the physical sense of having actual books. That, more than anything else, impacted what I did during my Meo Foundation residency. The closure of my definition pursuit presented me with a feeling of certain openness. I felt I could just draw freely as I worked. The shift in attitude meant I could be quick to decide and quick to make. I also felt I could be playful and call upon things I already knew. I could let go.

The As Is collages and assemblages are largely a product of that subtle but personal shift in approach. So, I began to search my collected texts for quotes about “nature” and then selected a bundle of them to work with. I had to ask Talin to photograph the first page of Kenneth Clarke’s Landscape Into Art, which I knew I wanted to make immediately, and that became the first finished piece in the series. Well, almost. There was another piece I actually made first that functions a bit like a herald announcing a play.

lemon juice, pencil on the title page of Le Maroc, Jean Célérier, Armand Colin, Paris, 1931

Early on in the residency, I made a kind of joke piece for myself that I did not think I would show anyone, let alone use in the series—an anagram homage to Marcel Duchamp on an unlikely title page from a book I found on the street after Porta Portese ended, on my first visit to the open air flea market. I went back into the work after thinking it was finished, and with my newfound focus, I added a second anagram that transformed the homage into a work about ecology. Given that I am indebted to Duchamp with regard to my studio practice, once I linked his studio practice to mine, I had to include it in the series.

Interlocking collage, pencil, watercolor, color pencil, and xerographic transfers on 20th-century end-page cuttings inset into 19th-century endpapers, document repair tape. Text insertion on left: Rev. J. L. Blake, A. M., Natural Philosophy, Lincoln & Edmands, Boston, 1829, p. 248

“NATURAL PHILOSOPHY, otherwise called physicks, [sic] is that science which considers the powers of nature, the properties of natural bodies, and their actions upon one another.”

But perhaps the most significant development was that my attitude shift allowed me to make work that points to the irresponsibility of capitalism in a bit more open, if mocking way. For a long time, I have been reading, collecting, and planning to develop a separate body of work about capitalism and landscape—I’m sure I will initiate that series at some point. But with the need to make work quickly while in Rome and have all materials in hand, I let go and just started making work to that end.

For example, in Actions [As Is No. V], the image on the left panel comes from a glossary of the namesake definition of a nearly 200-year-old science book. The definition contains a powerful message about “natural bodies, and their actions upon one another,” which does not seem to be in any of the other dictionary definitions I have collected thus far. I combined that definition with the symbolism of negative space between the two end pages of the collage, joined by another end page inserted into the center, which forms a kind of reclaimed tree with a transferred image of a man hiding behind both trees. The man who secretly witnesses an iceberg to his right, in his home vicinity, is implicated when all the elements are considered in unison. Actions is a work in which I subtly point to my own politics as I juxtapose the voices of others.

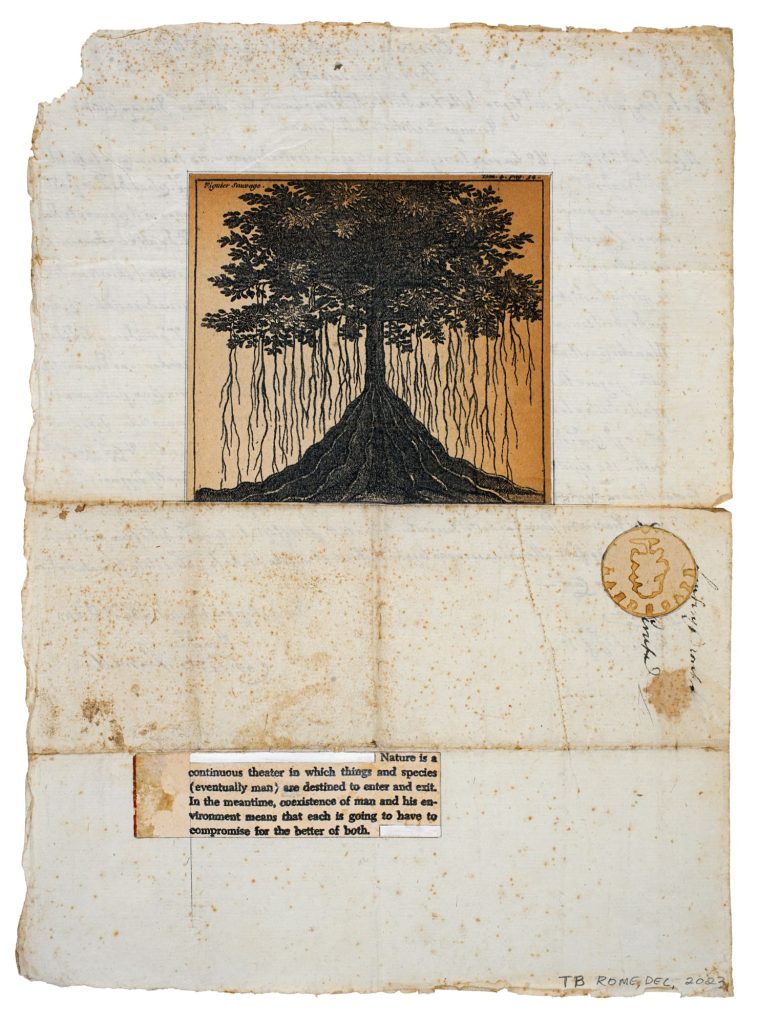

Interlocking collage, lemon juice print, pencil, color pencil, gouache, and xerographic transfers on 20-century end-page cuttings inset into 19th-century Italian letter, document repair tape. Bottom text: Christopher Stone, Should Trees Have Standing?, Discus Books/Avon, New York, special revised edition, 1975, p. 74

“Nature is a continuous theater in which things and species (eventually man) are destined to enter and exit. In the meantime, coexistence of man and his environment means that each is going to have to compromise for the better of both.”

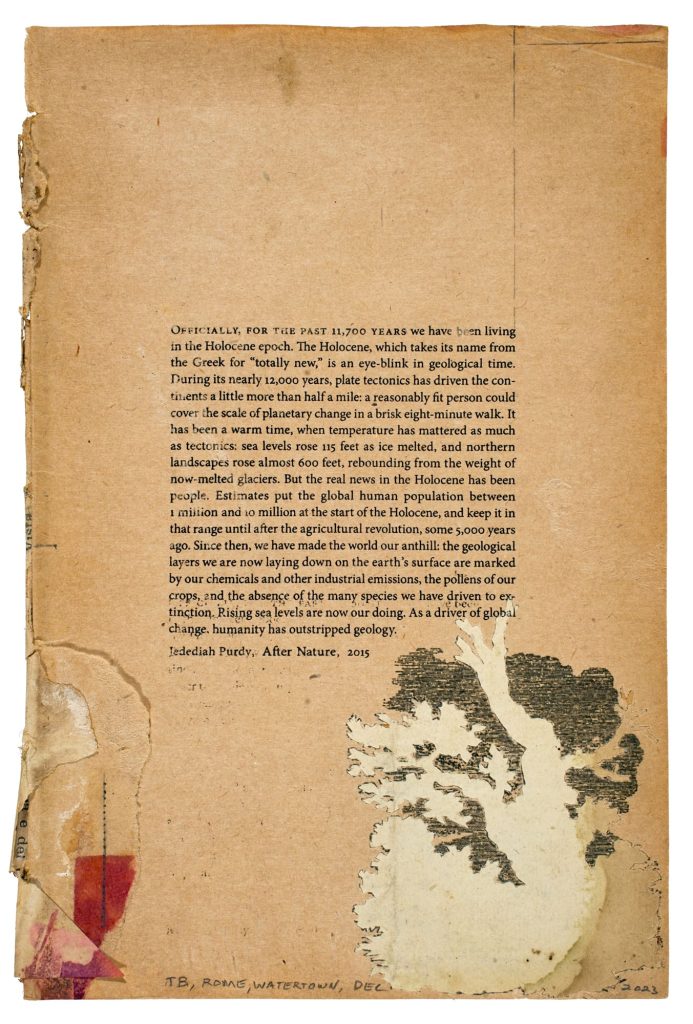

In the Western Judeo-Christian tradition, our perceived inheritance of Eden includes the proclamation of our “dominion” over everything, an attitude that links recorded history to the contemporary manifestation of our hubris, which, we think, gives US permission to ignore our impact on nature—we hide behind our capitalism. But as nature has been telling us, things are heating up under such footing.

Objet trouvé assemblage, ceramic doll feet, vintage iron, vintage Masonite found by Salvatore Meo

AB –Your piece, Vanitas, stands apart visually from the other works you have made in the series, yet you count it among your As Is collages. Can you tell us a bit more about this particular work?

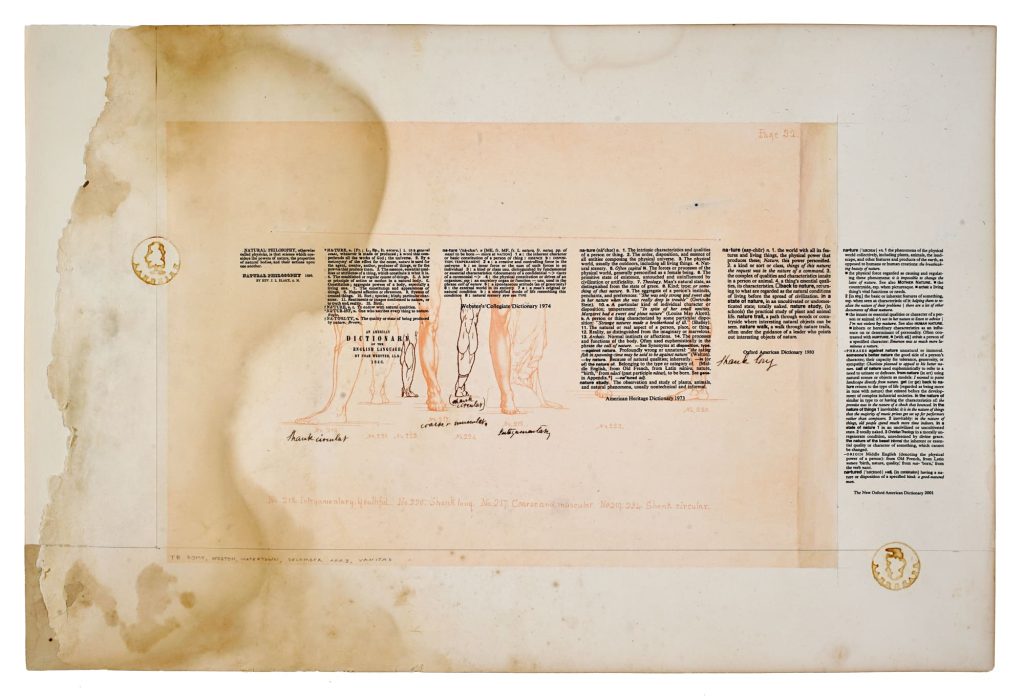

TB –It’s true. Vanitas usurps a readymade image, and other than my interlocking insertions of the “Landview” and “Landscape” citrus-inked stamps, there is no other interlocking collage image insertion. In this piece, the collected definitions have been imported and placed over the found image, and they stand in as the insertions for this piece; definitions juxtaposed with images of human feet.

Getting the definitions on the page was a challenge. I literally cut the parent page because it was too large to fit into a photocopier, and I printed my digital assembly of definitions directly on top of the excavated page—a hit-or-miss operation. Afterward, I had to tape the printed-on and cut-out portion back to its larger parent page. Since all the definitions center on the concept of “nature,” Vanitas relates to both the As Is series and the Landscape Vernacular series.

For my Landscape Vernacular show at Anna Maria College, I had already planned on putting my dictionary collection on display inside plexiglass-covered vitrines—the first time I had ever put my “museum” on display. Preparing my books for that show was the first time I saw the power of juxtaposing the collected definitions. Planning for that got me thinking about making a work exclusively about definition comparisons. After receiving the photos from Talin, I saw the potential to make a work of art about the difference in definitions while I was in Rome. The photo she sent me was used—with a little help from Photoshop—to create a high-contrast facsimile that could be transferred onto my collages. I began working on my first piece with comparative definitions just a few days later.

Seeing the definitions all in one place not only helped me solidify my direction while working in Rome, it also initiated a new venture to actively look for more changes in terminology related to landscape history. This past summer, for example, I discovered a shift in American dictionaries regarding the word “soil,” which for centuries meant “dirty” first and “earth” second. In today’s American dictionaries, “earth” is now the primary definition, which is a subtle way of concealing the “dirty” messes we have made by pushing them out of primary status in our terminology.

Xerographic print on water-damaged (with ink tracings by unknown author) page 32 of “Anatomy” by William Rimmer, Little Brown and Co., Boston 1877, with interlocking lemon prints on 20th-century endpaper cuttings, document repair tape

Technically speaking, even though it was the last piece to be completed and was put together at my home studio, Vanitas was the first piece I actually worked on during my first week of the Meo residency. I strung all the definitions of nature together digitally, printed them out at Trastevere Stampa—where I printed all the images and text I transferred to the As Is collages—and promptly brought the printout with me to Sala 1 along with the Duchamp piece and As Is (Surrounded) to discuss the development with Mary Angela Schroth before jumping whole-heartedly into my new venture. It may look different, but I consider Vanitas the Rosetta Stone of my studio practice, and it is literally the bridge that connects the work made on both sides of the Atlantic.

AB –You pointed out that you gave yourself several rules while you were in Rome. Did you abide by the rules you set for yourself for all the work you made?

TB –LOL.

For the most part, yes, but with my newfound freedom, I allowed myself what I considered to be minor breaches of my established rules. I broke my rule of only using things I could find in Rome for the As Is collages, with meaningful exceptions. Most of the images that I used for As Is collages came from a book I found in a box of discarded books on the street after the vendors left Porta Portese: a French novel by Pierre L’ermite, Comment J’ai Tué Mon Enfant (How I Killed My Child), with illustrations by Ludovie Gignoux, published by Maison de la Bonne Presse, Paris, 1926.

While I found that book in Rome, its text was in a romance language other than Italian, which initially gave me pause until I connected its title to my theme. When considered in concert with climate change, for example, the title of the book has powerful overtones. I link it to the projected demise of our children’s children in the age of the Anthropocene. That revelation led me to one of the early pieces in the series that confronts the Dutch invention of the term “landshap” with its etymological meaning of “shaping, cutting, and hacking” land.

Interlocking collage, lemon juice and ink print, pencil and xerographic transfers on 20-century end-page cuttings inset into 19th-century Italian letter, document repair tape

I selected five illustrations from Comment J’ai Tué Mon Enfant to work with. Other illustrations I used came out of the Natural Philosophy book, which I had already scanned while at Weir Farm and had on my computer in Rome. I used an image of an iceberg I already had on file. Similarly, I broke my materials rule in that I used digital images from my Landscape Vernacular series—the facsimile engraving of Wanderer Above a Sea of Fog and the engraving of the Savage Fig Tree from my piece, Proportions and Table Manners.

As I pointed out earlier, I made the As Is work quickly. All the choices for what to use were made during my second week of the residency. The selections for all the juxtapositions were made early, which meant that the rest of my work was perfunctory; I just had to put it all together. Most of the work was completed in Rome, but just a couple of projects were assembled at home—I noted where the work was done on the faces of the collages, and there are only two exceptions.

Regarding my pilfering from my other series, I saw the need for particular imagery that I wanted to use but wasn’t associated with Rome per se. It wasn’t that I could not find more things to incorporate from my Rome materials-gathering. It was that I realized that the series I was making in Rome easily connected to the Landscape Vernacular series as a related body of work and that it seemed important to connect with it in a physical way. It was natural and direct to pair the texts I selected to use in Rome with images already used that I knew would amplify the meaning of the juxtapositions, and I quickly pulled from my digital archives, sized images accordingly, and printed them out as needed.

Vanitas also broke my rule to only use Roman materials by using a piece of paper from a book not found in Italy. I allowed for this breach because it allowed me to connect the As Is assemblages to both the As Is and Landscape Vernacular collages while referencing another series I created some years ago. The acquisition of ceramic feet and a vintage iron at Porta Portese prompted an immediate possibility of extending my Grift series —a series of antique iron assemblages with attached objects that relate to landscape and climate change while playing off of Man Ray’s 1921 Cadeau (Gift). The ceramic feet, for example, provided an instant mental connection to William Rimmer’s 1877 Anatomy (Little Brown and Co., Boston)—a book that I have used in the Landscape Vernacular series for several pieces. I thought of a page from that book that had tracings of feet drawn over it, and I saw in my mind’s eye the potential of printing all the definitions of nature across the feet. Without doubting myself, I knew I would break a rule or two to make Vanitas.

As a related aside, there are three As Is assemblages that joined my Grift series. Finding the ceramic feet at Porta Portese enabled new connections and series expansion. As you recall, the first Grift assemblage was a paper construction I made for Michael Oatman’s “Object Lessons” issue of Cut Me Up magazine. After the Meo Residency, the Grift series is now seven pieces strong.

The last rule I broke was the exclusivity of making everything in Rome. I decided that since I wanted to make something with a material from my home studio, that I would do all the hard work in Rome and then finish things up as needed when I returned to the States. Whatever could not be assembled in Rome, I would assemble in Boston. I noted in pencil where each collage was made on the work itself. So, yes, I bent aspects of the Rome rules. I amended my rule to be that all work had to be started in Rome, but could be finished in Boston. My final rule was that I had to finish everything in December of 2023. I met that final criterion; Vanitaswas completed on December 31.

Objet trouvé assemblage, vintage iron, shoe sole and vintage Masonite found by Salvatore Meo.

P.S. Regarding rules, I also changed the titles of two pieces as I was writing my replies for this interview. Grift (Feet) is now titled Grift (Afoot); Grift (Sole), is now titled Grift (Soul).

AB –How do you navigate the balance between preserving the “as is” condition of found materials and incorporating additional elements to enhance the collages?

TB –Quite simply, the happenstance arrangement of natural markings on weathered surfaces is a type of visual utterance that I listen to because it suggests how to augment my own sense of compositional placement. I would answer this differently from one work to the next, but generally, there is another aspect of the time-warn that interests me. Well-traversed or well-used surfaces, like cutting boards and walking paths, show signs of wear and tear. Such markings exemplify inherent wisdom and possibility. I’m interested in things that last or change slowly over long periods of time and how they get recorded, saved, or repaired. While people come and go, objects and spaces witness their own slow degradation as the changes in the environment accrue the markings of time. Romans tend to repair rather than discard warn things; Rome is particularly a good place to witness this kind of erosion/maintenance — “Maintenance” in the Mierle Laderman Ukeles sense.

We think of marble as a very durable material, but in Rome, divots appear on stair edges, for example, after a thousand years of traversing stone stairs, and they need to be replaced. There are sculptures that get touched so frequently that metalsmiths are hired to fabricate facsimile feet and hand replacements that cover the worn parts and protect them from further damage. I have always loved the Roman system of repair: keep the old thing, cut out the worn bits, and replace them with new bits, or make facsimile replacements to go over the original thing—often with new materials that differ from the original materials used. The old with the unabashedly new. Accordingly, I like to leave torn edges as-is and leave holes in the paper unpatched. And when I do make repairs or add structural integrity to the paper somehow, I often trace the shapes to record the original damage as I insert paper supports. You can see this in how I have joined the damaged “worm-eaten” paper to another page in Actions (As Is No. V) and Dominion (As Is No. VI).

Interlocking collage, xerographic transfer on 19th-century Italian letter, lemon juice prints, ink, pencil and xerographic transfers on 20-century end-page cuttings, and “bookworm” eaten 17th-century endpaper with xerographic transfer inset into 19th-century Italian letters, document repair tape. Text at the bottom right: Christopher Stone, Should Trees Have Standing?, Discus Books/Avon, New York, special revised edition, 1975, p. 98

“It is commonly being said today, for example, that our present state of affairs—at least in the West—can be traced to the view that Nature is the dominion of Man, and that this attitude, in turn, derives from our religious traditions.”

What I like to call aleatoric drawing includes “wormholes,” foxing, mold, mildew, and general staining that paper endures and records. I tend to treat areas of erosion and wear and tear as readymade drawings and claim them as mine even though I did not make them. When I add to them or repait them, I refer to that as an assisted readymade drawing. (LOL. Maybe I should call them assisted readymade restorations.)

Conversely, and often, I try to mimic such markings and make them outright. For example, all the “landview” & “landscape” stamped images were made using rubber stamps I designed and stamped on found end pages with citrus, then heated so that the dried liquid would illuminate the residual images. I welcomed any random markings and incorporated them after putting too much liquid on the rubber stamps—whatever the spill looks like, I faithfully cut out. I used lemon juice on a lot of my As Is collages and then turned the otherwise invisible markings brown with the heat of an iron to cook the material into a noticeable—scorched—brown color. I love that you can control the color of the scorching by shortening or lengthening the time the lemon juice cooks under the weight, pressure, and heat of an iron.

I used Cosetta’s iron, which I was thrilled she had in her studio! Sometimes, I drip things or drag things across my papers—sticks, rocks, forks, and other non-traditional drawing implements—that have been loaded with ink, watercolor, coffee, tea, lemon juice, et cetera, as if some accidental marking occurred. It can be difficult to discern what is nature-made and what is artist-made in my work. Chance markings, or unintentional mark-making processes, are another shared interest with Salvatore Meo and are particularly evident in his drawings, which is why it was important to include two in the checklist of work I recommended for the As Is show.

Right: Salvatore Meo, senza titolo, disegno su carta (untitled, drawing on paper), 1958

I should add that when I leave the history of a piece of paper visible, it produces a kind of openness, and if I am fortunate, that “blank space”—the “Ma,” to borrow the Japanese term from the current issue of Cut Me Up magazine curated by Katie Blake—becomes like a vista and the paper provides a view into a perceivable distance.

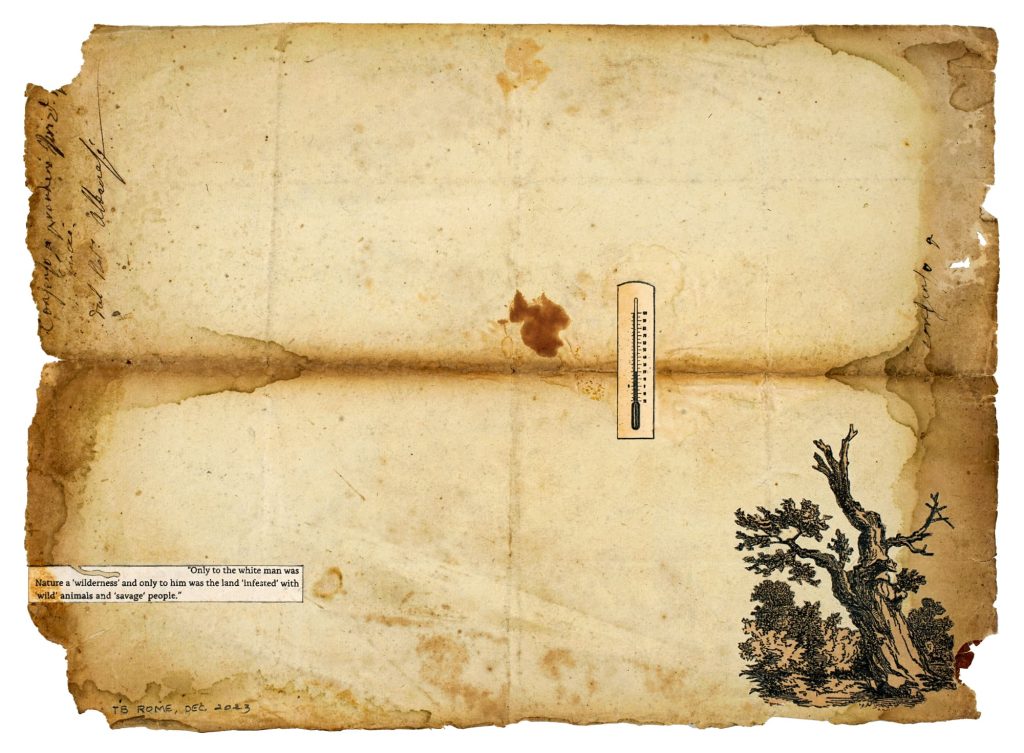

Interlocking collage, pencil, and xerographic transfers on 20th-century end-page cuttings inset into 19th-century Italian letter, document repair tape. Text bottom left: Standing Bear (Oglala Lakota Chief), quoted by Amitav Ghosh, The Nutmeg’s Curse, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2021, p. 64

“Only to the white man was Nature a ‘wilderness’ and only to him was the land ‘infested’ with ‘wild’ animals and ‘savage’ people.”

AB –You shared with me the three possible meanings of the phrase “as is,” the third meaning pointing towards the existing state of things and whether they should remain “as-is.” How do you hope these works, and this phrase, will resonate with audiences?

TB –I hope the darkest side of my As Is work and exhibition raises an existential question for my viewers.

Here, I think it is important to point out the thesis I have been working with for the past two decades by sharing it through the title of a “bridge piece” that sheds light on my rationale for including a Salvatore Meo objet trouvé in the As Is exhibition:

Assisted readymade, xerographic print on bond paper, vintage saw handle.

Salvatore Meo, Sine Lettera, (Sine Letter) assemblage in box, 1959

Interlocking collage, pencil, and xerographic transfers on 20th-century end-page cuttings inset into 19th-century end-page document repair tape. Text at center: Jedediah Purdy, After Nature, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2015, p. 1

Objet trouvé assemblage, vintage iron, rusted wire, toy Victrola parts

Collection of Fondazione Cosetta Mastragostino

As Is Exhibition Catalog available at Lulu.com

Landscape Vernacular Exhibition Catalog Available at MagCloud.com