Matt Dorfman is an internationally recognized designer and illustrator. He is the art director of the New York Times Book Review and former art director of the New York Times Op-Ed page. Additionally, he maintains a one-person office specializing in work for publishers, film, theater and various cultural institutions.

Please, introduce yourself, tell us a little bit about you.

I’m one of a few thousand designers and illustrators working in NYC. My working week is split, often unevenly, between a full time job that’s tempered by ‘the other thing.’ My full time job is at the New York Times art directing the Book Review—which I consider a legitimate privilege. ‘The other thing’ is the compulsion to keep making things after normal business hours. To that end, I still work on editorial illustration, book covers, the occasional brand project and very recently, a lot of uncommissioned collage.

As an illustrator you use a lot of techniques, collage being just one of them. What are the limits and the things you find more interesting in collage related with the other techniques?

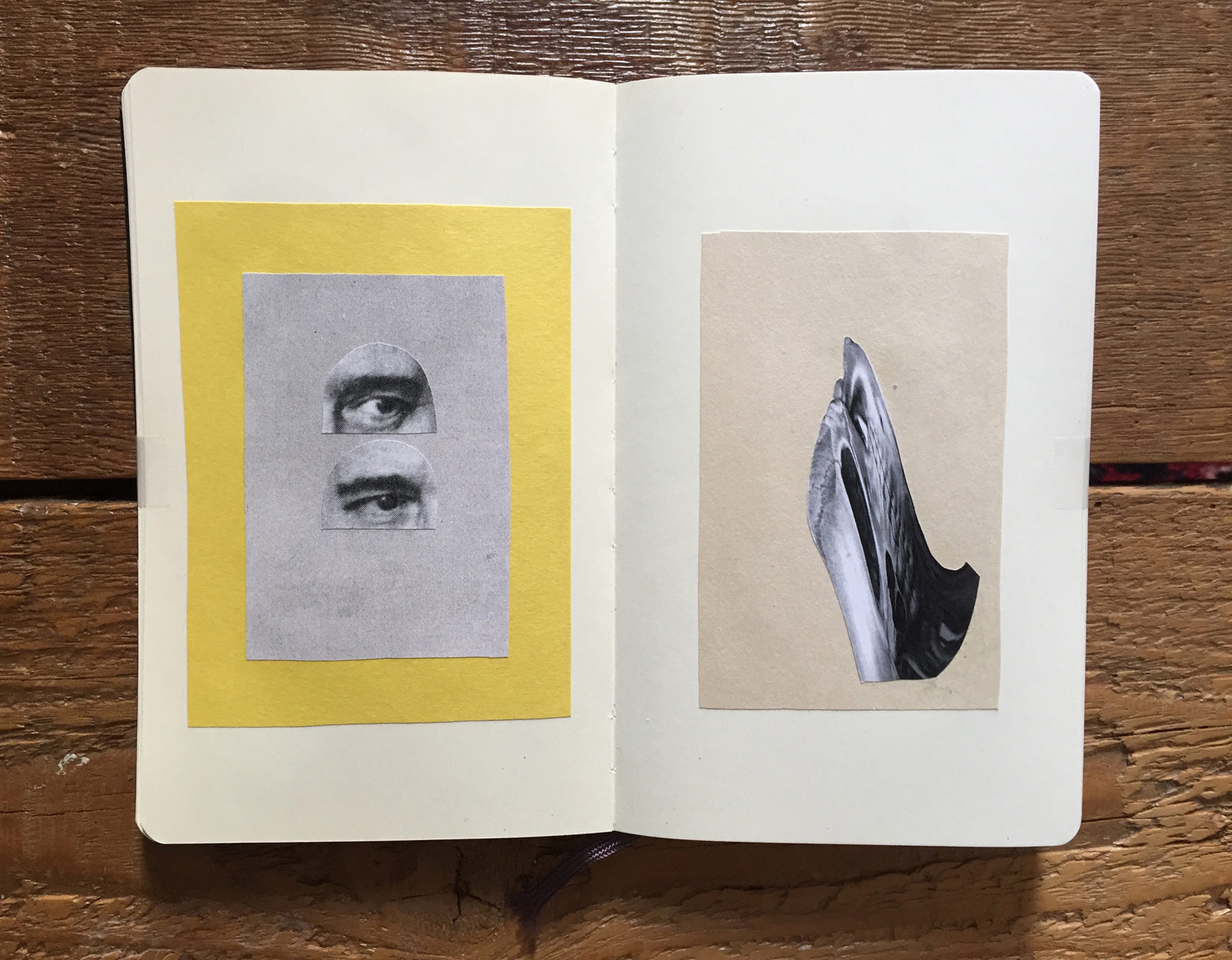

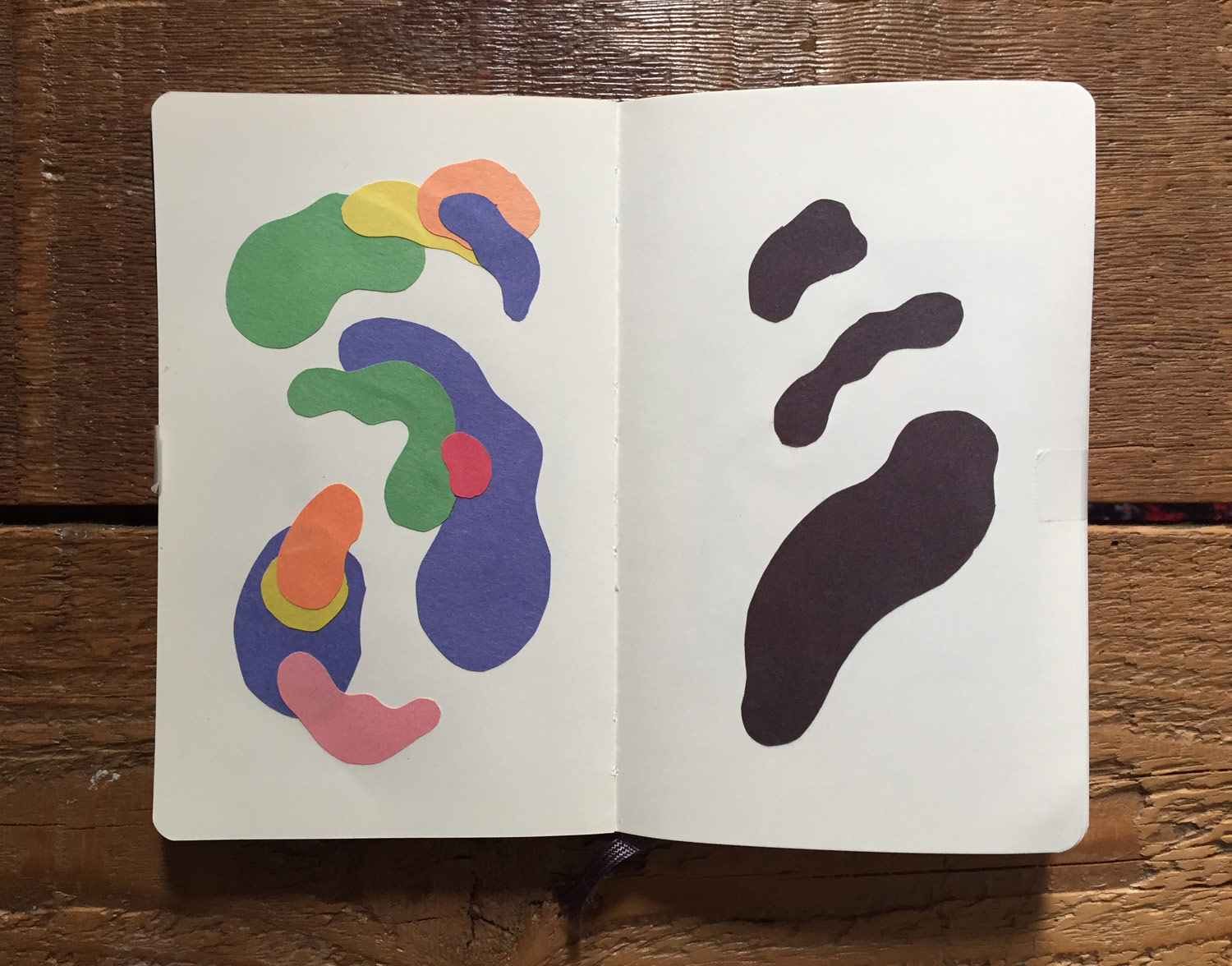

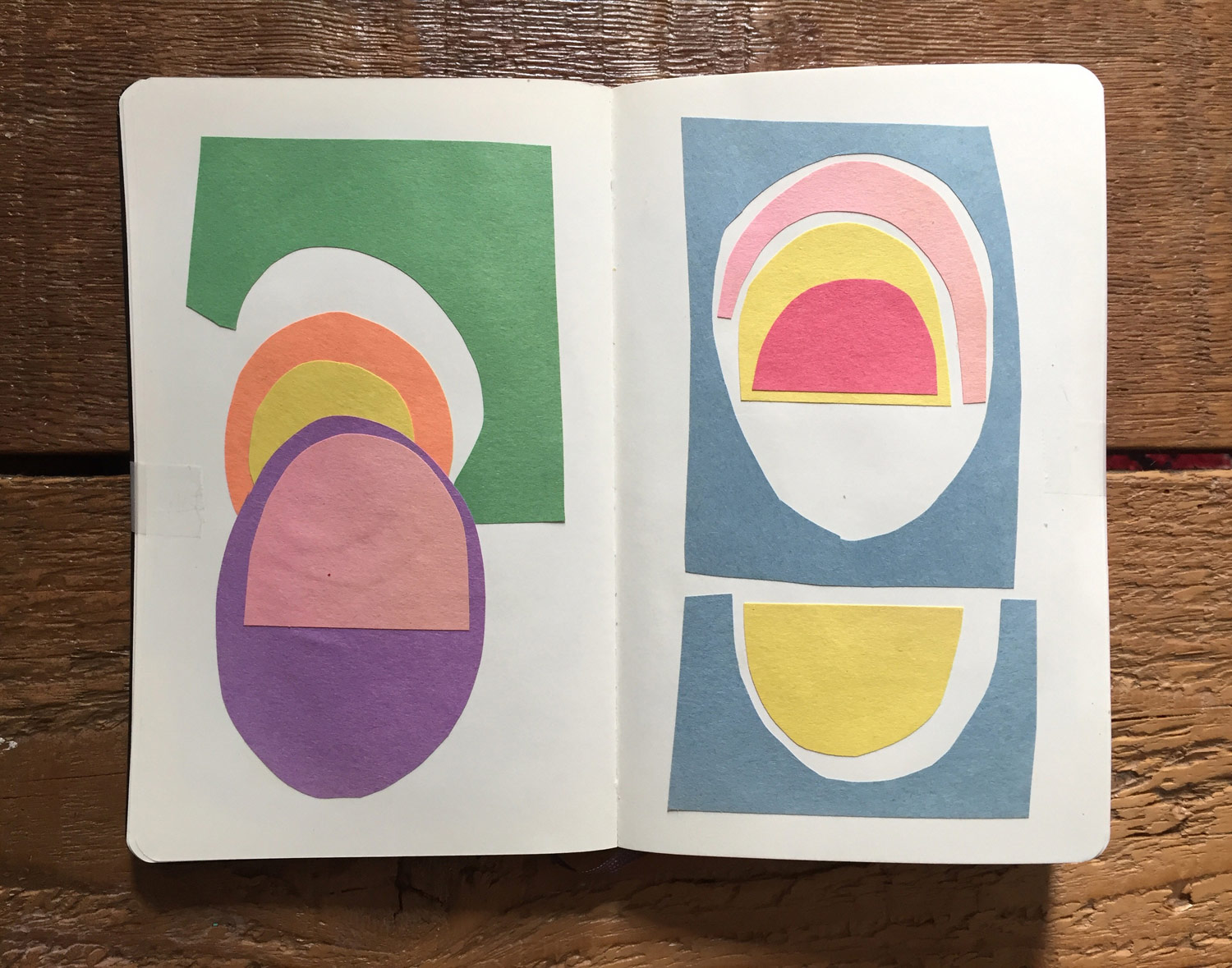

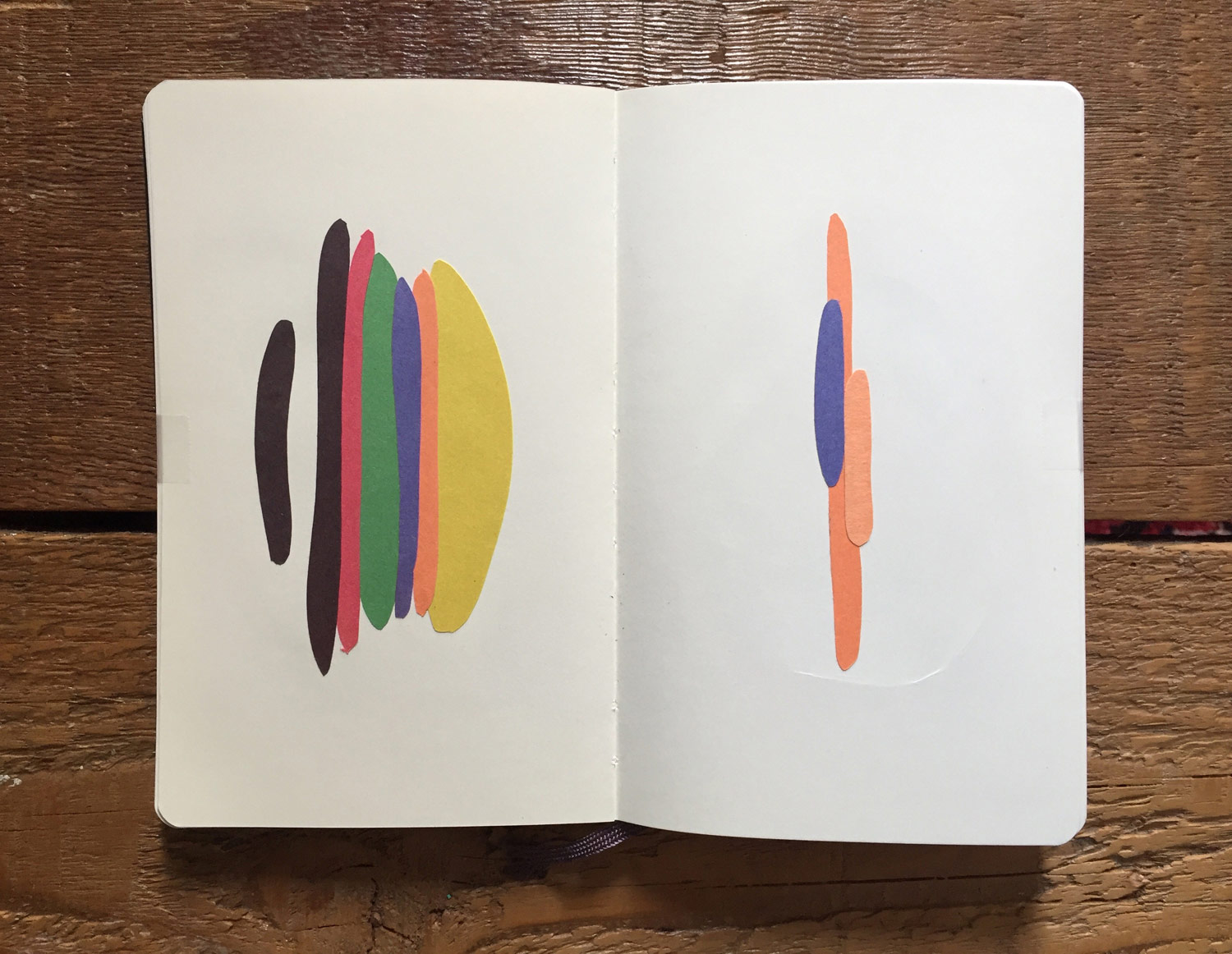

With my personal collages, I’m limited principally by how late I’m willing to stay awake and more practically, whatever pictures I have on hand. Much of the illustration work and the design projects I work on that involve collage depend upon the photos that are provided to me or if I’m able to shoot the pictures myself. For the personal ones I’m working on after hours, I’m deliberately restricting myself to using whatever’s laying around in my apartment. Earlier this year I performed a considerable purge of weird odds and ends that I had been collecting in a flat file for 20+ years; I kept particular things presuming that I’d end up using them for a commercial project at some future point but once I started working on the personal collages more and more, I became impatient. If something at work becomes frustrating or I hit a roadblock on a freelance project that isn’t going the way that I would have preferred, I’ll pick up scraps of my daughter’s construction paper and jump into my flat file and go to town in my sketchbook. The physicality of it serves as a good enough excuse for me leave my phone in the other room, go to my coffee table in the living room and cut things up.

You mention the physicality of collage. Is there any kind of nostalgia and going back to things we can actually touch in the middle of the digital world?

For myself, it’s less about nostalgia than it is manufacturing an excuse to be away from a screen for a while. Digital collage, if it’s done well, can be as exciting as the physical/analog sort—although I think there’s a different set of rules for each approach.

Scaling, placement and color options are more or less unlimited in approaching a collage digitally. Knowing that at the start of a project influences how I think about what I’m doing in ways which are good in terms of solving a narrative problem; but that same lack of limits cancels out the spontaneity and happenstance that makes the medium so much fun. Having unlimited tools has never really been a comfortable place for me for the same reason that having complete creative freedom is stifling. It’s difficult for me to see a point in making something which doesn’t require me to mind some kind of boundary, whether it’s a deadline or a story pitch or a matter of limited physical resources. Restricting myself to paper, a glue stick and an X-Acto is liberating because I can’t make choices with anything that I don’t have immediately on hand. Neanderthals, having few survival options themselves, behaved in the same way; Only they did it in order to forage for and sustain their families and live another day and grow humanity whereas I am a dude sitting on a couch who swiped his daughter’s construction paper.

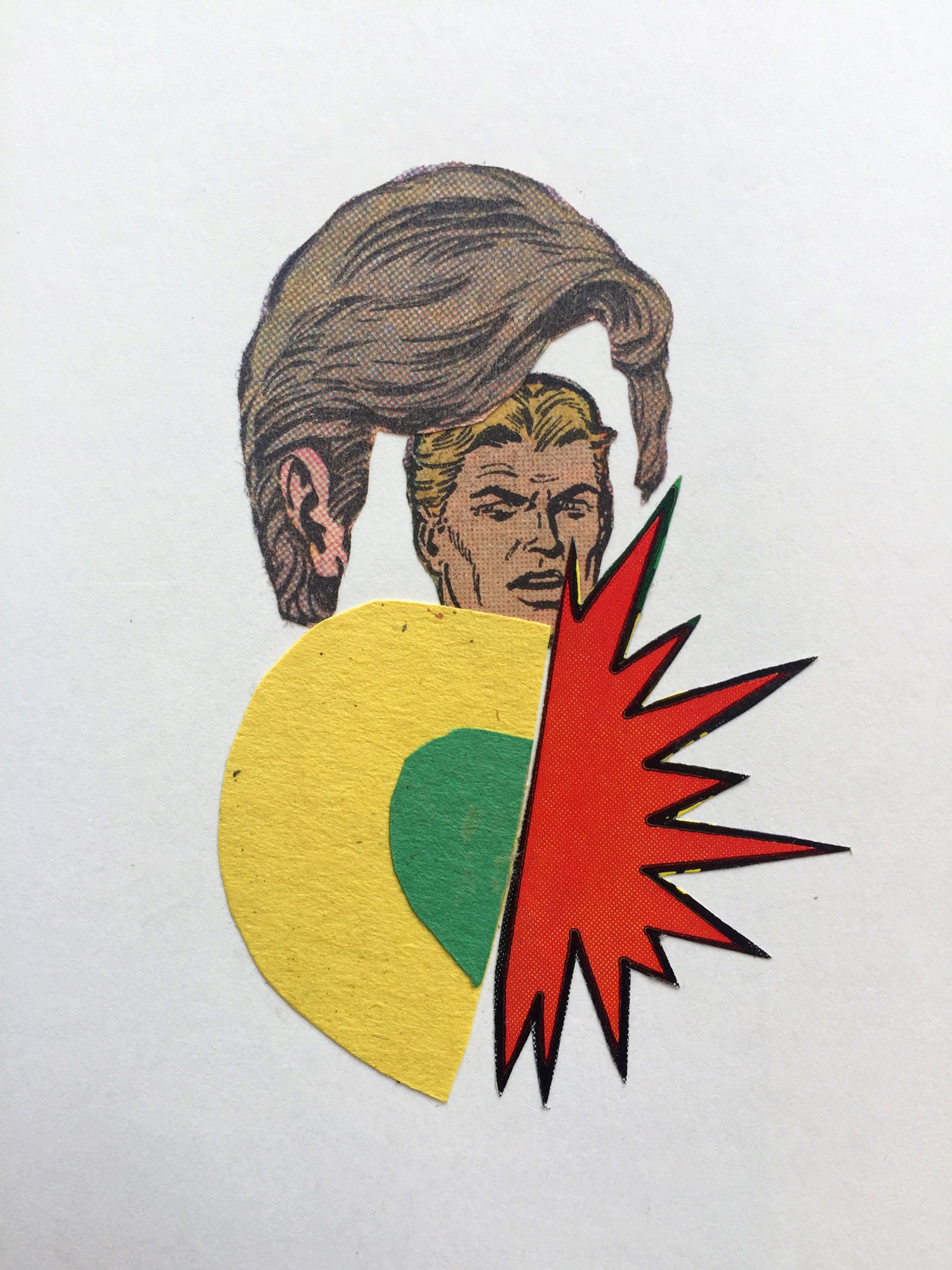

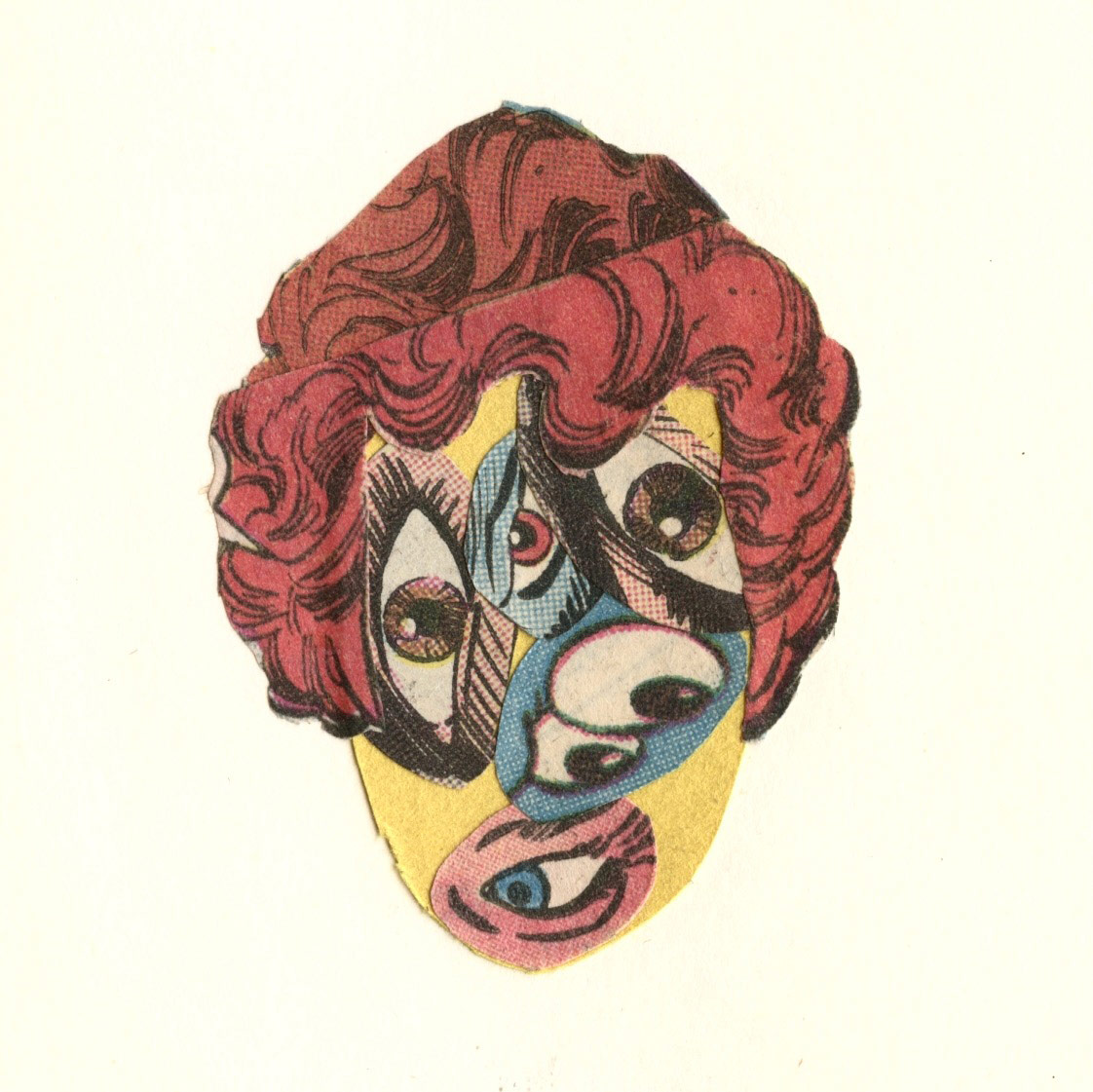

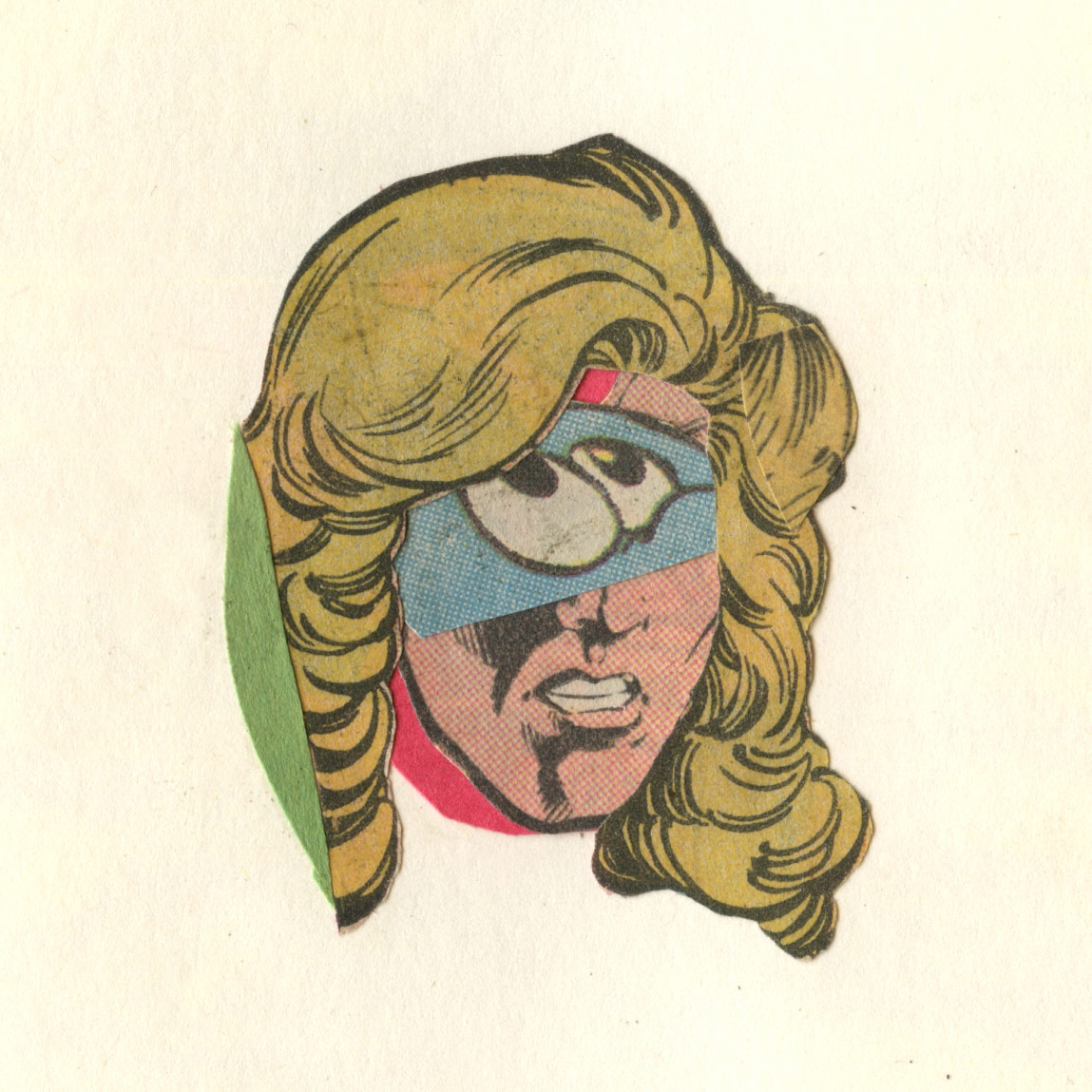

I was really impressed with a series of collages you had been working with old comic books. What drew you to comics and to start working in that series?

I am not a regular consumer of comics by any measure but I love their alarmist sensibility. Everything is always dependably confrontational and heightened. I’ve been drawn to emotionally high-pitched people for most of my life so it follows that I’d want to physically pick that behavior apart with my own work and comics are a pretty perfect vessel for that. I am not a regular collector of these comics either. Those collages were made using small bits and pieces from a stack of 10-12 comic books and they’re the only ones I own. I picked them up from various flea markets and vintage exchanges years ago presuming that one day I’d either use them as reference for something or cut them up and make something for myself out of them. I’m only just now getting around to it. When I’ve cut them all up and rendered every last bit remonstrated from their original intent I’ll go back out and buy 12 more and start over again.

What I love especially about what you did is that you somehow created new weird heroes and villains; it was like reinventing the the superhero genre…

Again, it’s the alarm bells going off on every panel. Every facial expression is urgent, all the eyeballs are bulging, all the people are shrieking and something’s always exploding. If I let myself go cross eyed, all of the action starts looking like really insane, beautiful abstractions on their own before I even break out the X-Acto. Jack Kirby, king of kings with regard to comic books, made collages with comics as well and they are unsurprisingly fantastic.

To the extent that we’re living through a ceaseless political crisis while simultaneously canonizing a lot of superheroes in movies, I think cutting them up in the way that I have has become an incidental coping mechanism for me to deal with this punishing news cycle. I’m not anticipating much justice or closure from the bad behavior coming out of Washington right now & making these abstract, senseless pieces is more and more my own private ineffectual way of venting those grievances.

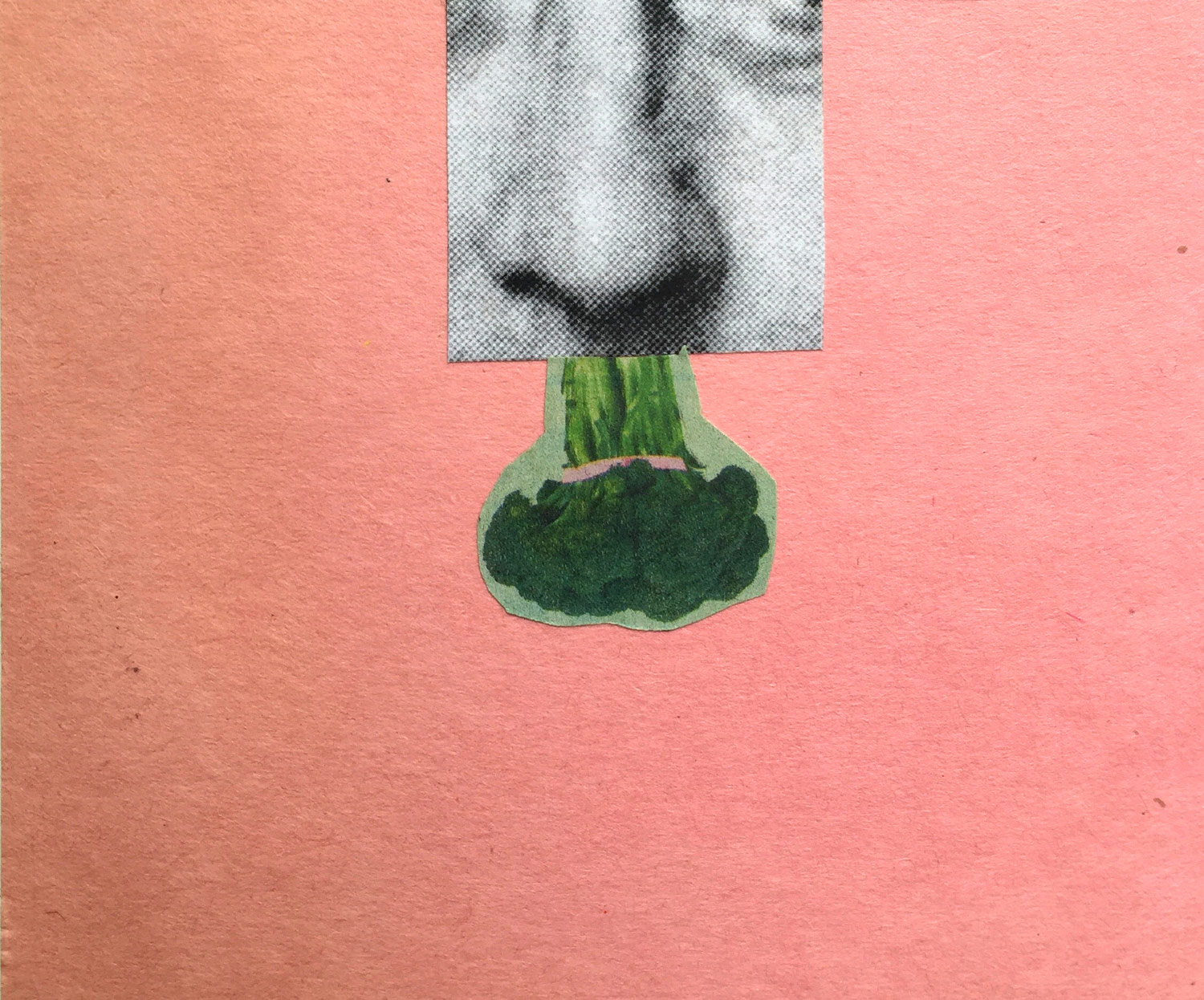

As an illustrator, how you deal with collage and copyright issues?

If I’m working on something for a publisher, I make a point to photograph any necessary reference materials myself. If that’s not possible, both my art director and I are very precise about what source material we’re using, where it comes from and we ensure that it’s legally purchased and cleared.

If it’s a matter of me sitting at home and chopping up old comics and old photos, I’m decontextualizing those elements completely and I’m taking care to use small pieces of pictures—never anything whole like a whole figure or even a whole face. I take copyright issues seriously for selfish reasons in addition to the practical and legal ones: I’d prefer that whatever I make not be mistaken for something someone else made.

In art maybe there´s some kind of gray area where people are used to work with images found on magazines or on the internet in the name of re-appropriation…

Yes, the infamous trials of Richard Prince. With reappropriations you are using an item that somebody else took time and care to make; so the extent to which you use that item to your own ends matters. I think it has to be transformed forcefully enough that the original source is wholly unconsidered and/or forgotten in the new work. The new work shouldn’t serve as a quiz to spot the reference. Ideally, it champions a new point of provocation. Unless you’re Richard Prince, in which case the appropriation becomes the provocation.

Some artists just combine a few elements and recognizable pictures…

…And some of them are stone cold brilliant. John Stezaker is always so great at creating such sharp, devastating associations between photographs. His curation and pairings are so powerful and deceptively simple that it masks how painstaking that process is. I’m completely ignorant as to how he navigates copyright issues with his work but I’d love to know.

How would you define collage?

At present? It’s the theft of my daughter’s art supplies. On an even more selfish level it’s an opportunity for me to for me to create freedom with a very limited means of expression.

How can collage evolve as a medium to avoid getting stuck in what has been repeating itself constantly?

Make a lot of work. Be self-critical. Don’t share everything you make. Most significantly, have fun & try not to treat it as too sacred a thing. Collage is as fun as it is because anyone can do it. Punk was embraced with the same egalitarian principle of empowering people to do what they wanted and play what they wanted and it’s loudness and messiness and chaos shares a lot with what makes collage so mischievous.

You mentioned Punk rock… sometimes my feeling is that collage today is what Blink 182 is to the original punk rock… something that is just mimicking a style developed in the past with nothing of it´s original concept or message. In my opinion collage sometimes is regarded more as a style than as a technique or a medium for artists…

Sometimes the sum of a collage might just be a style in search of an idea. But is that bad? Blink 182 might be readily accused of being all style in search of a point, but I don’t view that condition as a blanket negative. People who were born in the ‘90s or early aughts might embrace Blink 182 more than they ever would with The Clash (which is their right). But classics endure in ways that are mercifully bigger than individuals. I back-burnered The Clash in high school in favor of Bad Religion and other bands primarily because those other bands were playing live in my city on the weekends and The Clash were not. But The Clash worked their way into my heart in college and their music will stay with me for the rest of my life in a way that many of the bands I swore were my favorites in high school never could (save for a few distinguished exceptions). That cycle of exposure and appreciation is every bit as alive in visual art as it is in music and it’s a disservice to anyone’s personal growth as a creative problem solver to dismiss it. My earliest exposure to collage wasn’t John Heartfield or Hannah Höch, but once I was aware of them, recognizing each one as a master and a perennial inspiration followed fast.

The Clash, like Heartfield and Hoch before them, produced enduring work in part because it was beautiful while being in the service of something bigger than itself. Each one of those artists had legitimate socio-political axes to grind, and two of the very few upsides of living in a morally compromised world is that outrage and injustice might lead to positive change on a good day. In a distant second place, it may also yield great art.

And I don’t think that outrage is going away anytime soon. So as long as people who love scissors and glue and old pictures are cutting away and thinking critically and having fun and embracing all the freedom that the medium affords, the great, enduring work will keep coming.