In the first part of our interview with artist, professor, gallery director and historian Todd Bartel we discussed about more general ideas about collage as a medium. Now, we’re getting deep into his own work as collage artist.

TWS – You’ve been involved actively with collage since the early 80s. How do you see the evolution of collage as a medium since then? How do you feel the change of the century, the digital age, and those huge cultural changes that have affected collage? Is collage somehow different from how it was in the 20th century?

TB – I earned my BFA at a time just before conceptual art and political art changed the fabric of college and university art programs. My BFA education was mostly formal, with a heavy emphasis on materials and process. Ideas were discussed, of course, but the revered examples of art were not so much about establishing rules to create art by, and the art we looked at was not openly criticizing or questioning culture as much as it does now. It’s not that the art we looked at wasn’t conceptually provocative or politically potent. Like the rest of my peers, I was blown away by discovering Duchamp’s work and Barbara Kruger’s, among so many others. But the art we looked at and discussed tended to be emotionally and visually expressive, abstract, and intuitive more often than not. While collage was not generally a promoted strategy in most of my classes, both my two-dimensional design teachers during my freshman year—Hardu Keck and Alfred DeCredico—gave assignments that heavily relied on collage. Those assignments were my introduction to collage, and I fell in love with it instantly.

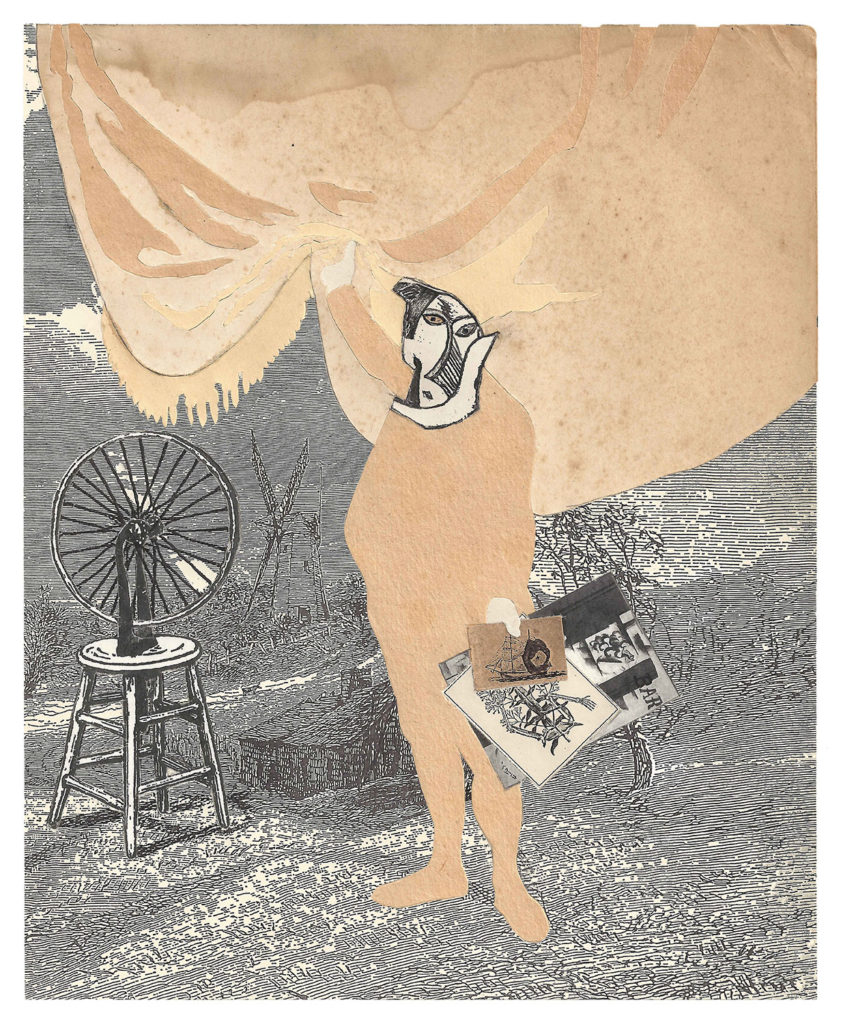

collage, magazine cutouts, rubber cement

10.25 x 6.125 inches

Collage changed how I approached artmaking. During my sophomore year, I was screen-printing with layers of translucent ink, superimposing images on paper, and layers of glass or plexiglass. By my junior year, I began inserting magazine clippings into my paintings and soon afterward my drawings became collages. I consider those prints, paintings and drawings my first mature body of collage-based work.

screen print, Rives BFK

15 x 11 inches

I entered into grad school as the digital world grew into being, and I grew with it. But it was not until just before the turn of the century that digital tools became invaluable for me in any serious artistic way. Today the fusion of digital technology into my art practice is so thorough most people cannot distinguish between the elements that I find in books that I purchase, from those elements that I fabricate myself and print onto period paper.

The first significant shift that I witnessed in collage since the 1980s was during the last decade of the 20th-century, when collage practitioners used the medium for overtly political and conceptual strategies. This is not to say that Dada, for example, wasn’t conceptual or political in form and content, because it was. What I experienced was probably more of a personal reckoning, because I myself began to shift away from formalism in order to move toward cultural awareness as being front and center and I joined the overall cultural trajectory. Increasingly, I found myself noticing collages about Feminism, racism, identity and gender politics, and the critique of capitalism. There is such cacophony of intermingling isms, styles, and varied content today, statically speaking, that it would be challenging to say there is more political art being made today then there was in the 1980s—but I think that is probably true for collage in general. As an emerging artist, during this time period I certainly became attuned to its prevalence as I myself moved toward blending formalist concerns with with political and conceptual ideation. What I can say is that back then it was not that common for artists to write artist’s statements; “that’s the job of curators, historians and critics,” I would hear my teachers say. But today, it seems rare if an artist does not have some kind of statement to accompany their work. The transition occurred in a relatively short period of time. Collage was a well-established vehicle for such political realism, which tended to show up as assemblage, installation, and time-based media work—all descendent applications of collage. Seeing and experiencing that transition was a delight for me because while the rest of the world did not see these media as collage-based, my colleagues and I did!

I would say that there have been dozens and dozens of advances in collage in terms of possible collage operations since 1912– the year that Braque first added sand and dirt to his paintings, while Picasso added a collaged oil cloth and a rope to one of his. Braque also began playing with papier collé, then Picasso, and after that, Modernism exploded with myriad ways to engage with collected and incorporated imagery, which artists did not make themselves. It was not that Braque and Picasso invented collage—examples of collage and assemblage go back to the first peoples who lashed sticks and stones together, and, wore fauna skins and wove flora into patchwork clothes. In the common era, Europeans confined the depiction of reality in strictly illusory ways after the Renaissance. (During the Dark Ages, European imagery was confined to iconic depiction.) What is so significant about the advent of modernist collage is that it expanded illusionism to incorporate actual artifacts from the world in so much as depictions of forms and spaces were part illusory and part actual. Since then, artists have continually expanded collage possibilities—frottage, exquisite corpse, décollage, chiasmage, rollage, appropriation, to name a handful of key possibilities.

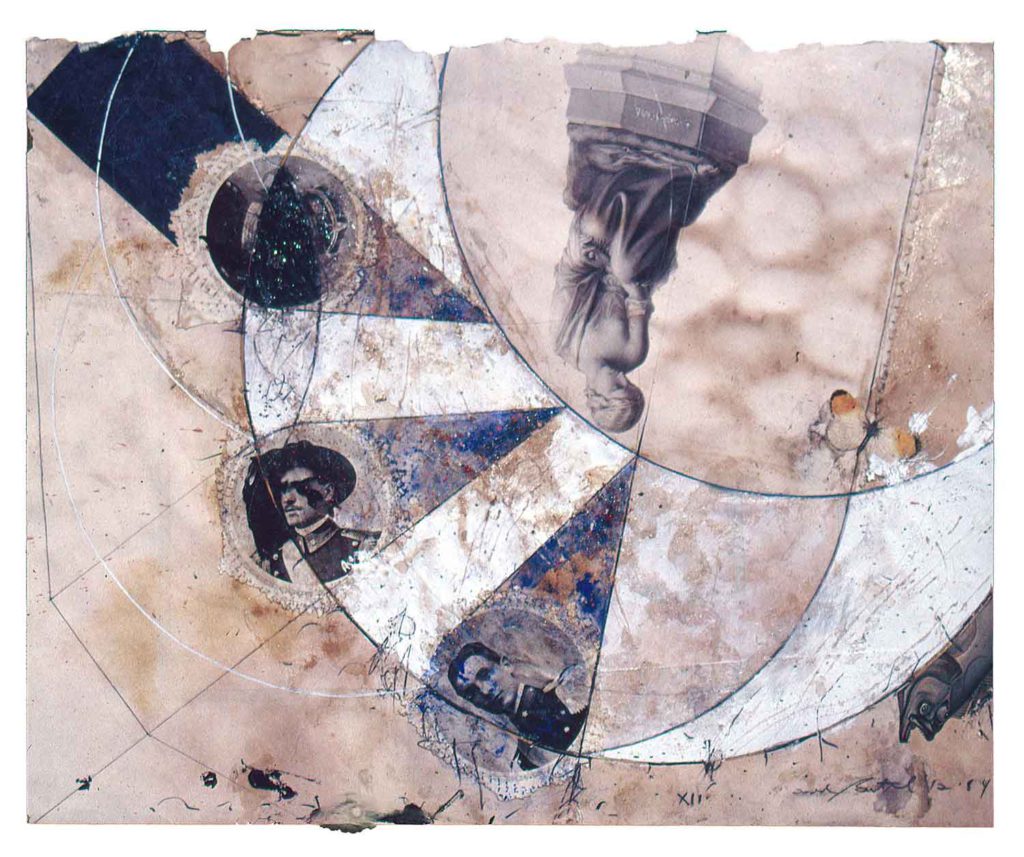

cutout bookplates, glue wash, watercolor, Odd Fellows Union yearbook cutouts, wax, gouache and pencil

on back of page from a Florentine book (Book of Kings c. 1900)

13.75 x 17.75 inches

But recent advances occurring on my watch since the 1980s include, as you rightly point out, “the digital age”: Photoshop, GarageBand, iMovie, 3-D printing, laser cut collage, and Instagram, but also, Bio art and nano collage (I keep saying Nano Collage hoping that artists en masse will push this possibility). Photoshop enabled us to combine representations of reality with seamless precision. Anyone can digitally cobble together music recordings and movies today. 3-d printing allows us to place any combination of forms out of drawn or scanned representation into physical spaces. And Instagram (Facebook and social media in general) fosters a decentralized collage community. It used to be that you had to live in Paris, Zürich, Berlin, or New York, to name a few key cities, to interact in the avant-garde movement of the day. Today, there is a decentralized collage community that is active, growing and thriving on Instagram. I found TWS because of the kinds of accounts on Instagram I tend to follow; you put out a call and I answered! These recent digital advances do indeed have a profound impact on what (collage) art is like today, and they also impact how we experience it—for better and for worse.

digital imaging, laser-cut collage (cut at Kennedy Fabrications, New York, NY) Rives BFK, mounted on museum board

22 x 30 inches

What I love about the advent of digital collage is that you do not need glue or paper to make a collage anymore. Digital collage, in my estimation, is one of the more significant developments in the history of collage because it forces us to redefine collage as not being dependent upon paper and glue—uncollage. If ever collage is to be celebrated appropriately beyond its distinct decoupage applications, we need the definition of “collage” to expand beyond such materiality. Collage is how we understand the world: we put things together to survive, we put things together to express ourselves, and we put things together to evolve. Collage broke down the barrier between the depiction of reality and reality itself. It imported bits of flotsam and jetsam, bricolage, and readymades into the creative act. Collage is the nouveau réalisme. Perhaps instead of realism, we should call it “actualism.” But what I do not like about screen-based art is that it seems to be distancing people from going to see the physical objects to some extent and more alarmingly, the digital boon seems to be distancing the new generation of artists from making physical works. A growing number of digital artists are preferring virtual spaces and materials for the actual ones—in the last year I my students increasingly beg me to make art by dragging their fingers across smooth glass screens instead of dragging physical materials across the grain of paper. I don’t think we will stop making analog collage, but it is interesting that those of us who do make physical objects feel compelled to note on our Instagram accounts that we make “analog” collages just so our audiences won’t confuse what we do with virtual collage.

I remember my first fear that arose the moment I saw the first few films with significant CGI. I feared that we would see film, TV and news that confused the reality of current events in misleading ways. On a positive note, it was quite a moment to be able to visualize dinosaurs moving upon the earth for the first time! Seeing “Jurassic Park” was a truly extraordinary experience. Seeing a (CGI) dinosaur in motion on the large screen brought tears to my eyes—it still does. Growing up, I was limited to the dragging tails claymation versions of Jurassic life. But that film made it visually believable beyond effects. It was a sublime moment in my opinion, equivalent to the wright brothers Kitty Hawk flight and the Eagle Landing on the surface of the moon. But that moment was not only celebratory, it came attached with some fears too. My first fear was that someone could make a fake film depicting President of the United States saying anything they wanted, and then that could create myriad problems in the world. All this digital manipulation of course has devolved into a world filled with “fake news,” “alternative facts,” and disinformation. And so that too has become a product of the digital revolution.

One thing I did not expect was that Surrealism would become so commonplace in today’s films and ad imagery that making good works of surreal collage has become harder to accomplish because culturally speaking, we have “seen it all” and we are used to such riffs on reality. Who knows where this will lead us, but collage got a considerable boost with the digital revolution, and more is on the way, to be sure.

TWS – As an artist, gallery director, writer, and art historian, you relate to collage from many different angles. Which is the place you feel collage has in contemporary art?

TB – Collage infiltrates contemporary art and life thoroughly. Its place is ubiquitous—it’s everywhere. In my opinion, collage is the most important form of communication ever developed because it is the only form of communication that is 100% inclusive. No other form of communication can do what collage does. Collage, in the broadest sense of the term, can incorporate anything.

TWS – Can you tell us about why landscape is so present in your work?

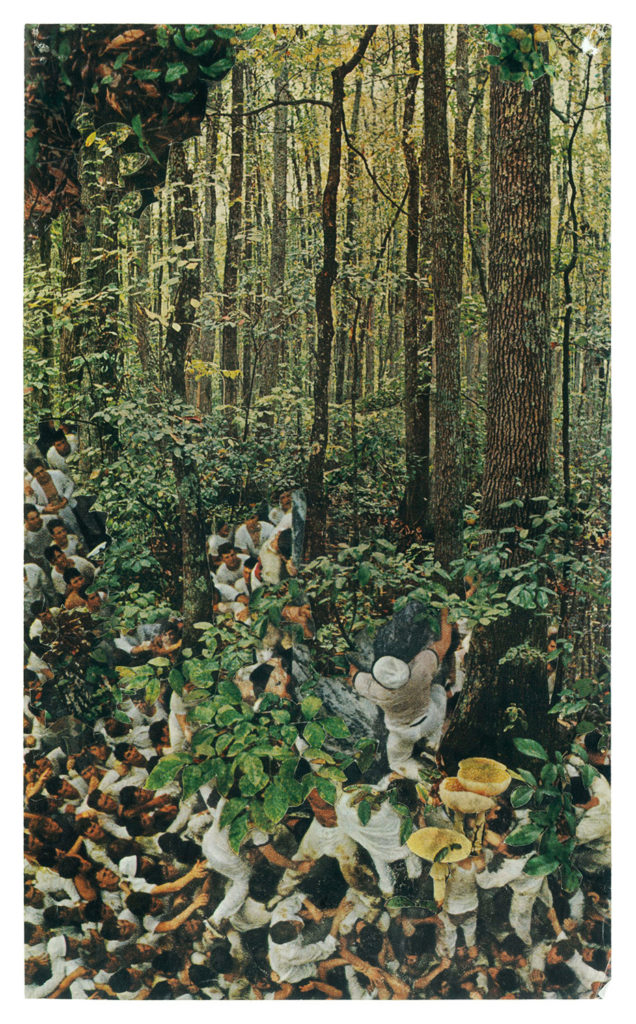

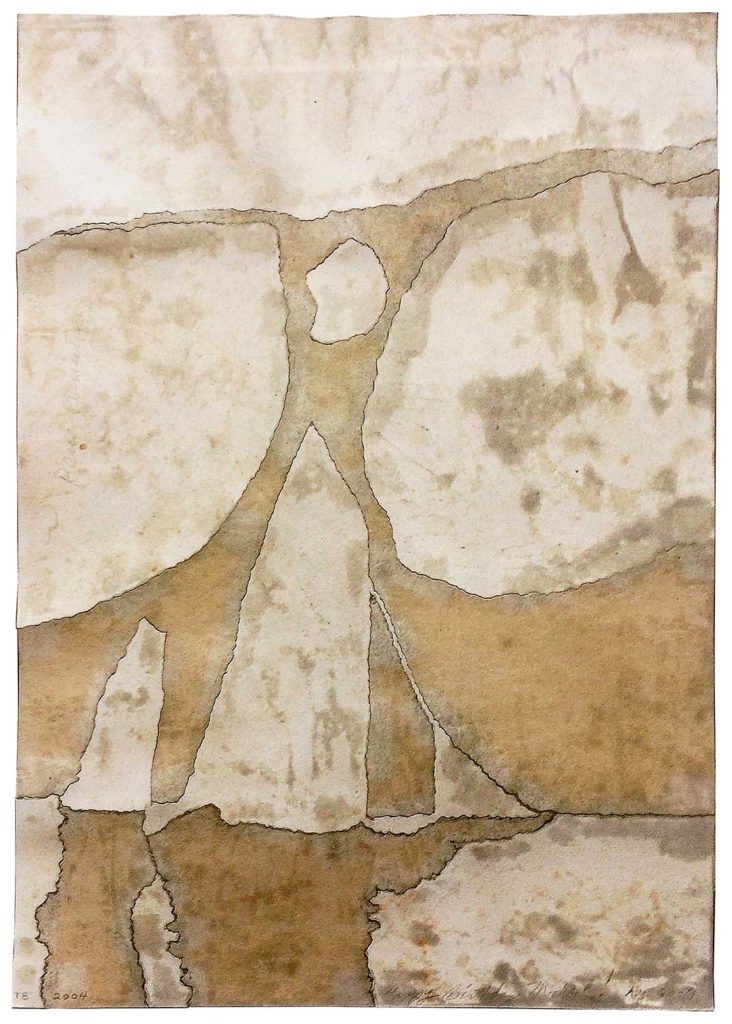

TB – The funny thing is that landscape and collage have been present in my work since the early 1980s when I first adopted collage as my artistic base. I laugh when I see it, but my first collage was a landscape, my first screen prints were about landscapes, and my collage paintings were about landscapes. I just did not realize my intuitive leanings then! When I applied to attend graduate school however, I consciously created three new assemblages for my applications—Trilogy of Unknown Martyrs—which were designed to discuss the late 1980s cutting back of the African and South American rainforests. I saw that global trend as a catastrophic problem. I thought to myself, why would we want to cut back the engine of carbon dioxide/oxygen conversion? It bothered me then and still irks me now. In 2000 I revisited the topic with Abulic Terrain—the first piece in the Salvage series. I credit Trilogy of Unknown Martyrs as my first conscious work as an eco-artist. But even though I cared about environmental issues back then, I did not realize “landscape” as the primary subject of my studio practice at that time.

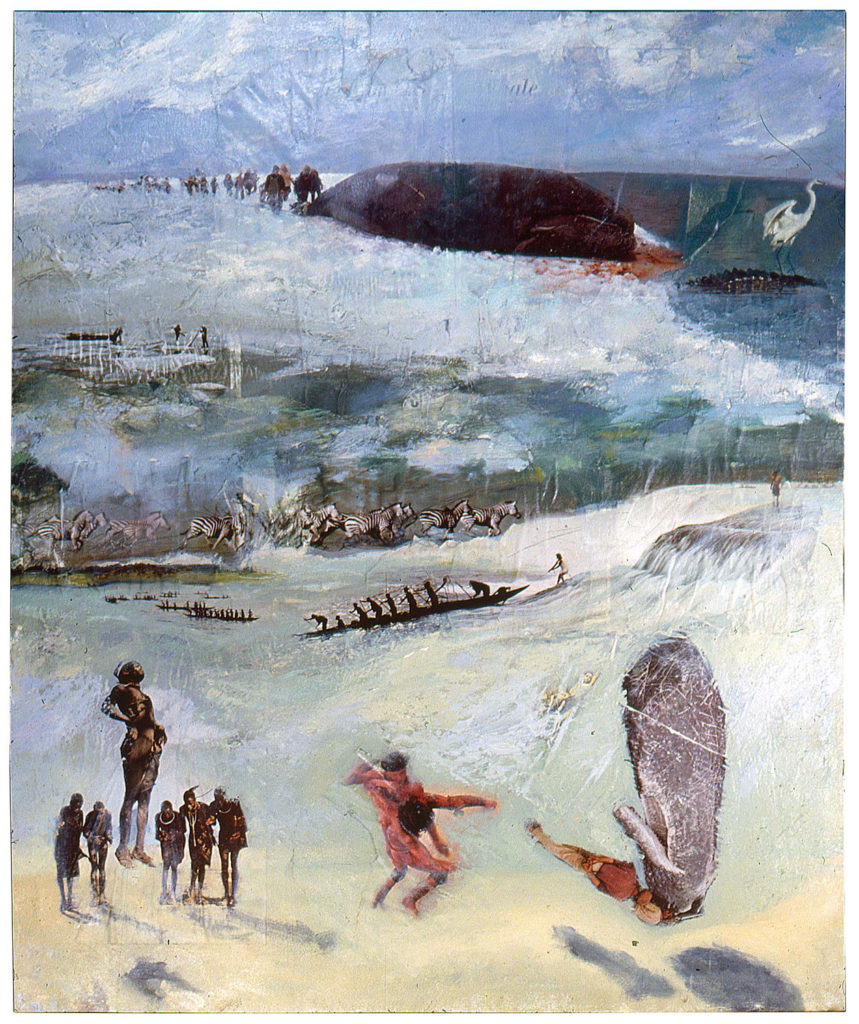

oil, collage, ink, canvas

30 x 25 inches

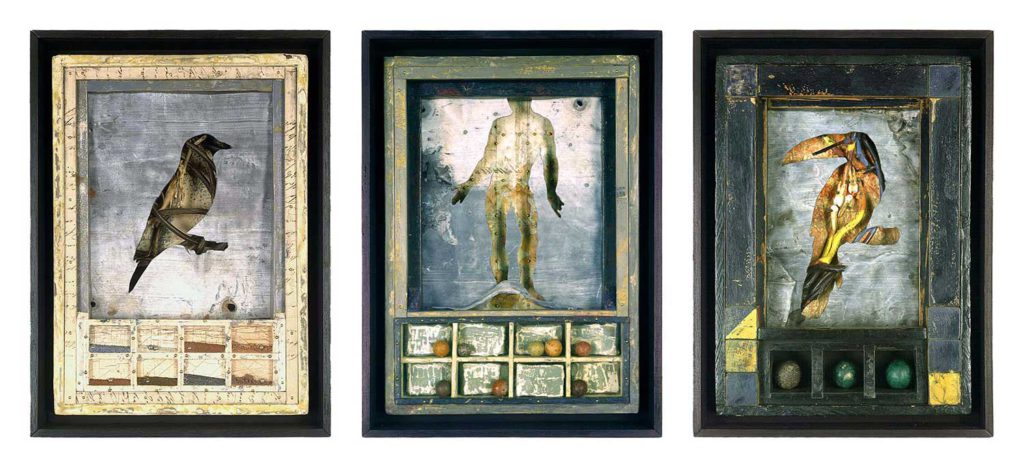

tempera, casein, Italian letter (c.1880), twigs, thorns, cloth, lead, ball bearings (number of bearings correspond to the age of the owner of the “Trilogy”), sand, dirt (Kenya, New Mexico, Block Island), wood box, glass

13 X 9.75 X 3 inches. Photo credit: Alan Weller

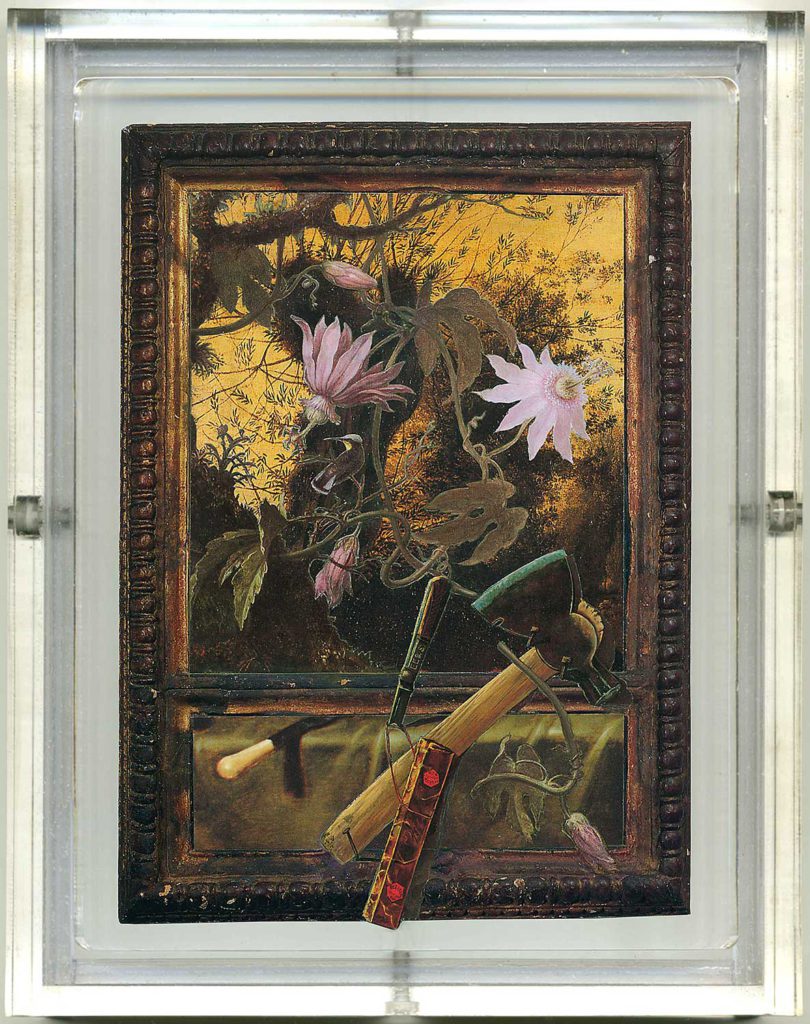

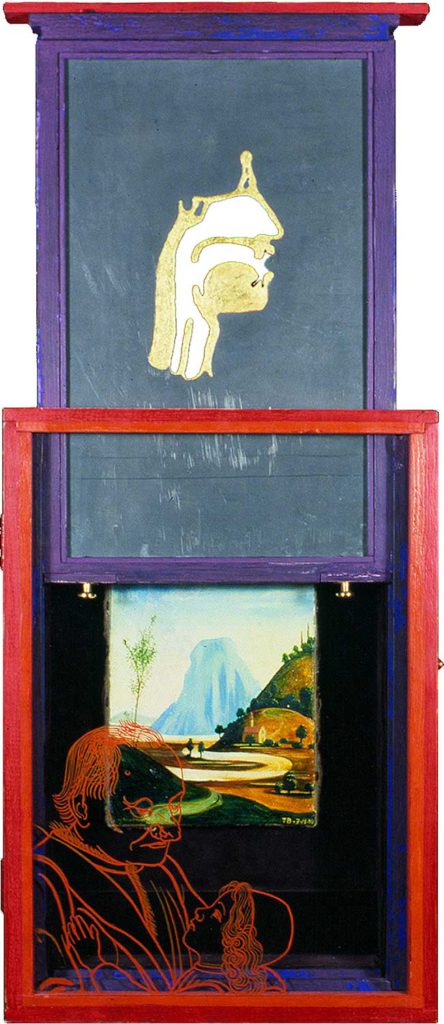

constructed wood box, old paint-chipped wood unearthed after second bucket-loader scoop dumped it’s contents at local dump while the artist was in search of green-paint-chipped wood; anonymous painting c. 1900, found in Maine antique shop; cobalt glass eyewash cup (purchased on route to deliver the artist’s boxed constructions requested for inclusion in the exhibition “Memory Boxes,” Lebanon, PA), casein on wood form, root (harvested at a dried up reservoir near Stamford, CT, the day before the artist’s spouse, Talin Megherian’s water broke and four days before she went into labor with their son Noah), mustard seeds, India ink on snakeskin given to the artist by Olivia Tow (a 2nd grade student at the Mead School, of Stamford, CT, who serendipitously brought a snakeskin to school on the day the artist had requested one from Olivia’s science teacher who did not have one), Museum Glass

23.375 x 24.25 x 5.5 inches. Photo credit: Robert Puglisi.

When I was in grad school, I began to apply ideas of appropriation in my studio practice, and I naturally gravitated toward landscape imagery. But it was not until after earning my degree that I discovered Simon Schama’s 1995 “Landscape and Memory,” which I credit with my awakening to the theme of landscape. That was the book that inspired me to focus on the history of landscape.

In his book, Schama discusses the etymology of the word “landscape” as being a Dutch artist’s term and that its roots in language involve “cutting and hacking land.” That bothered me the moment I read it because, as someone who cares about environmental issues, I did not like that the word “landscape” was etymologically associated with “cutting and hacking.” When I look at a landscape, a panorama, I’m not generally thinking about cut up and hacked land. I am just seeing the space before me. Sometimes peoples protect and preserve land, and it occurred to me that we need a word that does not conjure ideation about land rearrangement when we set aside tracts of land for cultural or natural preservation. So my first body of work to directly adopt eco-art was my Terra Reverentia series, for which I developed a new word to sharpen the dialog: “landview.” That 1995 body of work initiated my dedication to all things landscape related and I have not strayed from this focus since.

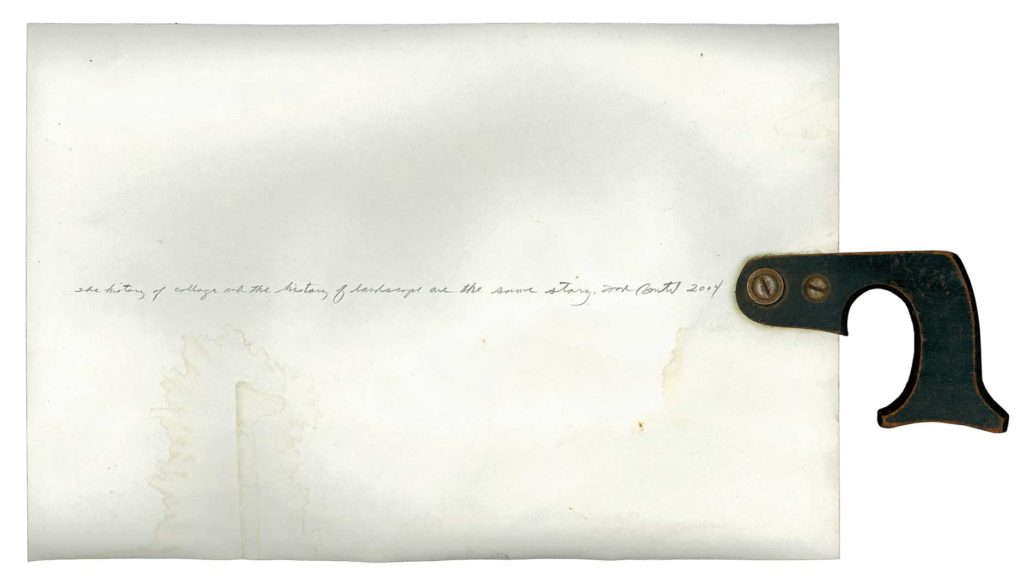

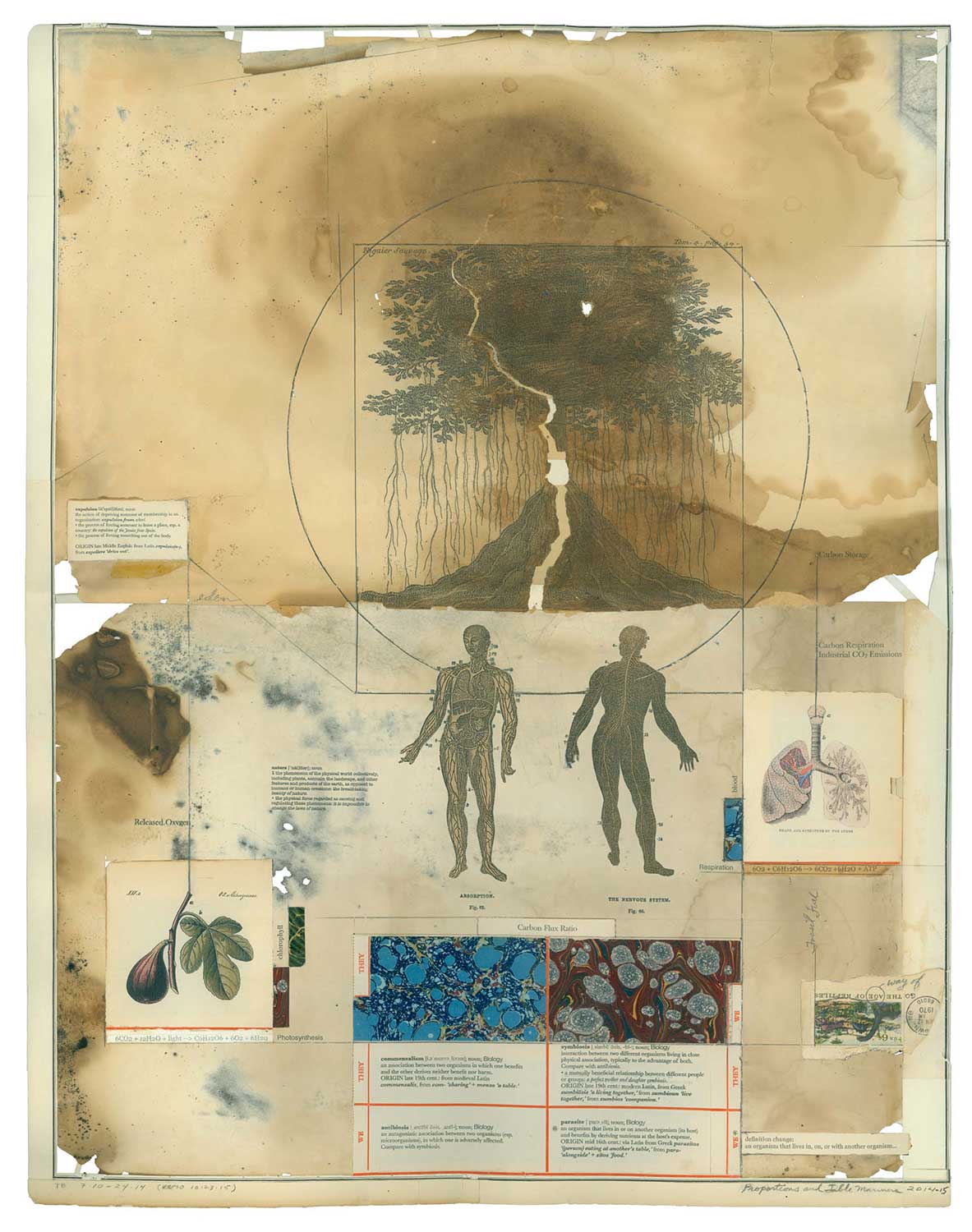

My research led me to make the claim, “the history of collage and the history of landscape are the same story.” Since 2000, I have been actively trying to illustrate this concept in my studio practice, and that has me very busy! There is so much work to do that I’m not sure I will ever finish what I have set out for myself. My basic thesis is that collage traditionally uses material that comes from the landscape—paper for example. Likewise the history of landscape ultimately developed from depicting land as it was imagined and witnessed. The separate practices of making collage and making landscape imagery were not particularly brought together as a movement in its own right but by the middle of the twentieth-century when artists began using tracts of land to make their art with. Land Art and eventually Eco-Art became foci in their own rights, which both make use of collage practices and expanded collage strategies. These two histories have collided many times over the last 50+ years—not only in my work. Agnes Denes’ “Wheatfield—A Confrontation” is a fantastic example of importing the unexpected into a worldly location—collage. (The natural glue used in that site-specific intervention is of course “lignin,” which, I just realized, I need to add to my list of Nature-based glues!) Thus, both histories are intrinsically tied and must be considered connected to the same history.

Burnished puzzle-piece fit collage, antique papers, Xerographic prints on 20th & 19th-century endpapers,

pencil, document repair tape.

10 x 8 inches

burnished puzzle-piece fit collage, antique papers, Xerographic prints on 20th & 19th-century endpapers,

pencil, document repair tape

7.25 x 10.75 inches

TWS – Can you tell us about your no-waste technique?

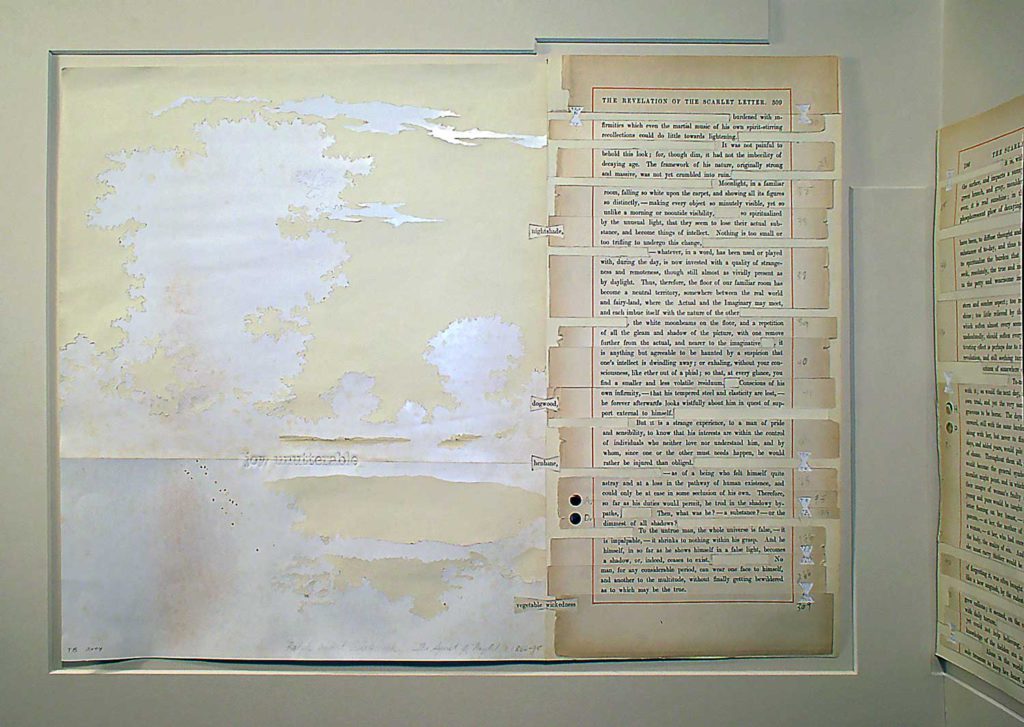

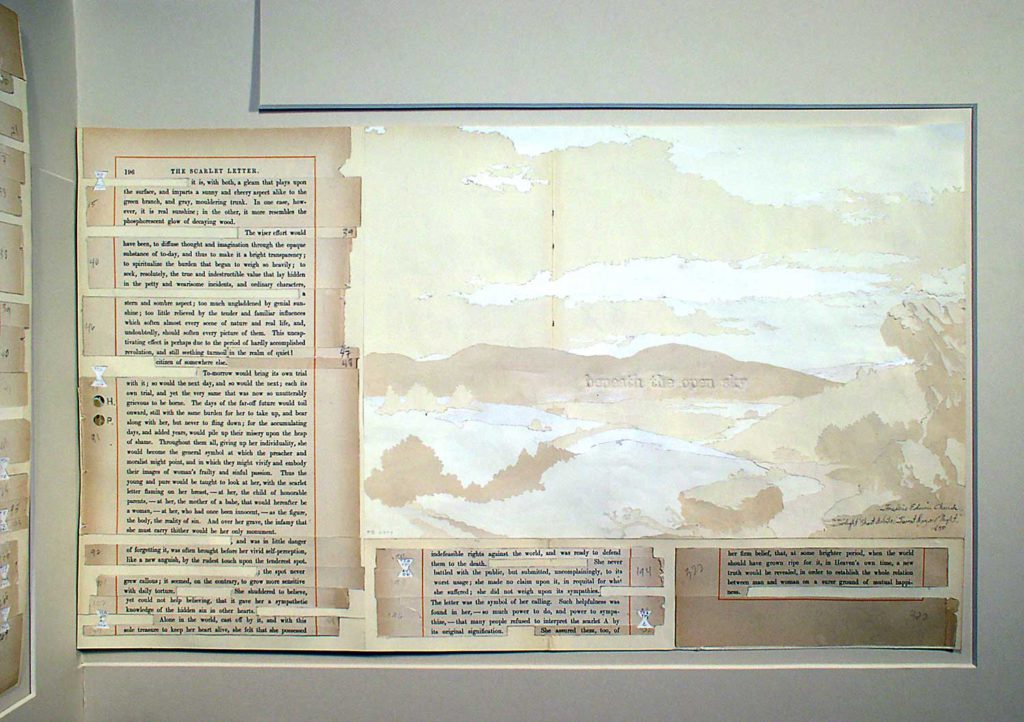

TB – In the early 2000s, I began to criticize my collage practice for the leftovers it produced. What do you do with the cutoffs? I have always tended toward using my cutting byproducts and have not thrown them away since 1983 onward. But I realized at that time that I was actively thinking about ecosystems without having a conscious plan for my cutoffs. Mindless collage byproducts bothered me given that I was trying to create mindful eco-conscious art, until I devised ways to create collage with little or no waste. Because the very act of cutting an object out of a page leaves a gaping hole, I wondered how I could incorporate both positive and negative forms together to eliminate waste. I have generally preferred the negative space over that of the positive object since my mid 1980s collage work. For me, the object in absentia is invoked in spite of its apparent absence. I find the negative shape and the removed object to be powerful imagery. By the early 2000s I began to wonder what might happen if I cut the same thing out of two pages simultaneously because that would allow me to exchange and replace what I removed with a surrogate that was the same precise contour. That idea spurred the puzzle-piece-fit collage process, which I have been practicing for 20 years now.

puzzle-piece-fit collage, book page cutouts

10.375 x 7.25 inches

Puzzle piece collage process

Water Over the Bridge, 2017-2018

recto: burnished puzzle-piece collage, 19th and 20th century book end-pages, dictionary definitions, 20th century map, 1880 Italian letter remnant, Xerographic print on 20th century book end-page (R. Dodd, engineer, Design for a Stonebridge, 1799, Plate III, “Report (1800) from the Select Committee Upon the Improvement of the Port of London,” proposal for the refurbishment of the London Bridge), Xerographic transfers, watercolor, graphite

11.825 x 16.75 inches

The first body of work I created with this technique was my “Blank Paper” collage series. Finding paper was a problem. I began collecting end pages from antique books, but typically there are only two of these in any single book and collecting them was a slow and wanting process—early projects have unwanted seams because I did not have paper large enough for my own ideas. When I had enough resources, I expanded my Synterial series—a series of shaped frames designed to reflect the content of the work being framed—to include blank paper collages. (See: The Box Does Not Need To Be Square: An Interview with Todd Bartel, by Nance Van Winckel) That early series work quickly led to several more series that each utilized the puzzle-piece process.

To cut puzzle-piece collages, I hold an image in place on top of 1-5 stacked sheets of different toned endpapers, while making precise perpendicular cuts through all the layers simultaneously. Once the cut elements are released, I exchange the parts with the other pieces of paper and assemble multiple, single-surface collages—as many multiples as there are stacked pages. The process yields zero waste in the instances I make multiple works. In the case of the Witness series the negative spaces surrounding the selected objects are put onto the backs of their respective frames—so the waste is kept as a document of the process but is otherwise not visible to viewers. In addition to always paring the two Witness image exchanges together as diptychs, I also create ridiculously long titles for this series by mashing up the actual names of the appropriated images and objects. So even the identities of the original items are recycled. In the case of the Real Landscape series, what is left over is saved for a “remnants” collage series that I have yet to initiate, but that waste is minimal and it will eventually be recycled and used. The zero-waste waste projects are very satisfying in terms of how all cutouts are utilized by the end of the process. Every cutout, once exchanged, helps to complete a kind of cloned copy of itself. If I cut out a stack of 4 icebergs, using 4 different shades of white paper for example, by the end of the process I have 4 separate works in the semblance of the same iceberg intermixed with cut pieces of each shade of white paper. These are very time-consuming collages to make, but I love the possibilities that arise from the process. Several of my current series makes use of the technology: Blank Paper; Witness; Real Landscapes; Designer Landscapes, Synterial series; Blank Slates & Tabula Rasa; and currently, the Landscape Vernacular series—a series inspired by John Brinckerhoff Jackson’s Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, within which is an in-depth etymology of the word “landscape” and the source Schama referenced in Landscape and Memory.

burnished puzzle-piece collage, watercolor, document repair tape, book page, auction house catalog page

10.5 x 7.875 inches

Witness [11b right]: Thomas Cole, Oxbow: The Connecticut River Near Northampton, 1846 with A Library Table Top, George III, circa 1790, (A Tabletop for Mark Tansey),

2018

burnished puzzle-piece collage, watercolor, document repair tape, book page, auction house catalog page.

6.75 x 9.75 inches

burnished, puzzle-piece collage, using auction house catalogs, with archival tape, in artist-designed Plexiglass frame

4 15/16 x 7 inches; w/ frame: Framed 7 x 9 1/2 inches

TWS – Why do you favor old and antique paper in your collage work? What conceptual issues does that decision respond to?

TB – I reach for vintage materials because my work reflects upon the timeframe in which my materials existed. For me, 19th-century and 20th-century materials hold clues and prompt reflection about attitudes toward land, landscape, and natural resources. Western culture’s notion that nature is separate from humankind also regards natural resources as infinitely abundant. The Industrial Revolution capitalized upon natural abundance in unprecedented depletion of resources. I work to understand our capitalistic society, which values monetary wealth at the expense of natural resources, and so, I am interested in Industrial era materials, ideas, literature and art. 1800s materials are expensive but are more abundant and more affordable than those from the 1700s, and so I work with what I can acquire. The choice to limit my production with age-specific materials is conceptual, ecological, and political.

To be fair, I love collecting old things. There is wisdom in a thing that has survived the harsh conditions of time, environment, and ownership. Moreover, to bring a thing from the past into the present moment is like saying we are not done thinking about that thing or time yet. I love that the things I collect often show the patina of time. The first teacher of the Dao, Laozi, wrote in the “Daodejing,” “great perfection appears defective…great fullness seems vacant.” The great Daoist philosopher Zhuangzi once said: “That which is rotten turns magical.” I love deteriorating paper because of the atmospheric quality it suggests. Within the flatness of aged paper, a vista becomes possible.

two diptych puzzle-piece collages using 19th century paper and The Scarlet Letter remnants (Nathanial Hawthorne 2nd Edition, Riverside Press Cambridge MA 1878, Illustrated), with 20th Century matte and glossy paper, Filmoplast P90, pencil and lead letter type transfer, mustard seeds, glass, etched glass, copper tape with patina, 19th century stereoview postcard (“View of Salem and Vicinity ”) archival matt, in handmade (“bent”) frame that turns 90º in order to reside in both sides of a room corner.

Each half of the bent frame measures 20.625 x 23.25 x 1.625 inches

“The Spirit of Night,” 1889

TWS – You mentioned to me that you consider collage as an “unfoldingobject.” What’s the idea behind this definition?

TB – “Unfoldingobject” is a term I coined to describe that quality in a work of art that inspires repeat looking. It is a virtue today to slow down and appreciate something handmade. With the history of the world now available in the palms of our hands through smartphone and tablet technologies, anytime we are in the presence of a work of art that refuses to deliver content in one viewing, we experience true wonder. I like to call artwork that captivates attention with each viewing, an “unfoldingobject.”

constructed wood box, tempera, lead, gold leaf, pressed flowers, plaka on glass, velvet, brass, oil on linen, ink

30 X 12 X 5.5 inches

The word itself is a collage of two separate words, joined together to form a single word. An unfoldingobject yields connections and meanings with each viewing. I think collage as a medium has excellent potential to produce unfoldingobjects, and that is why I curated an exhibition last summer on the topic. To view the exhibition catalog please visit https://issuu.com/thompsongallery/docs/unfoldingobject_catalog.small. I value mystery and connection-making in a work of art and I coined the term to do honor to that quality in art that slowly unfolds over time.

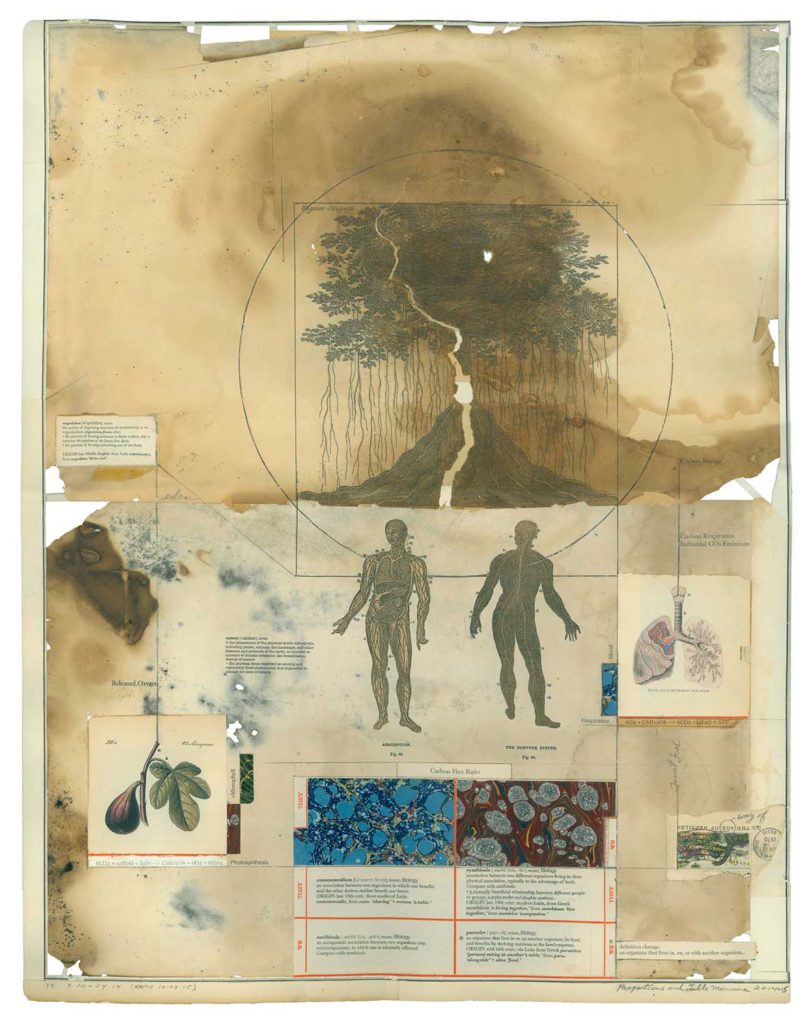

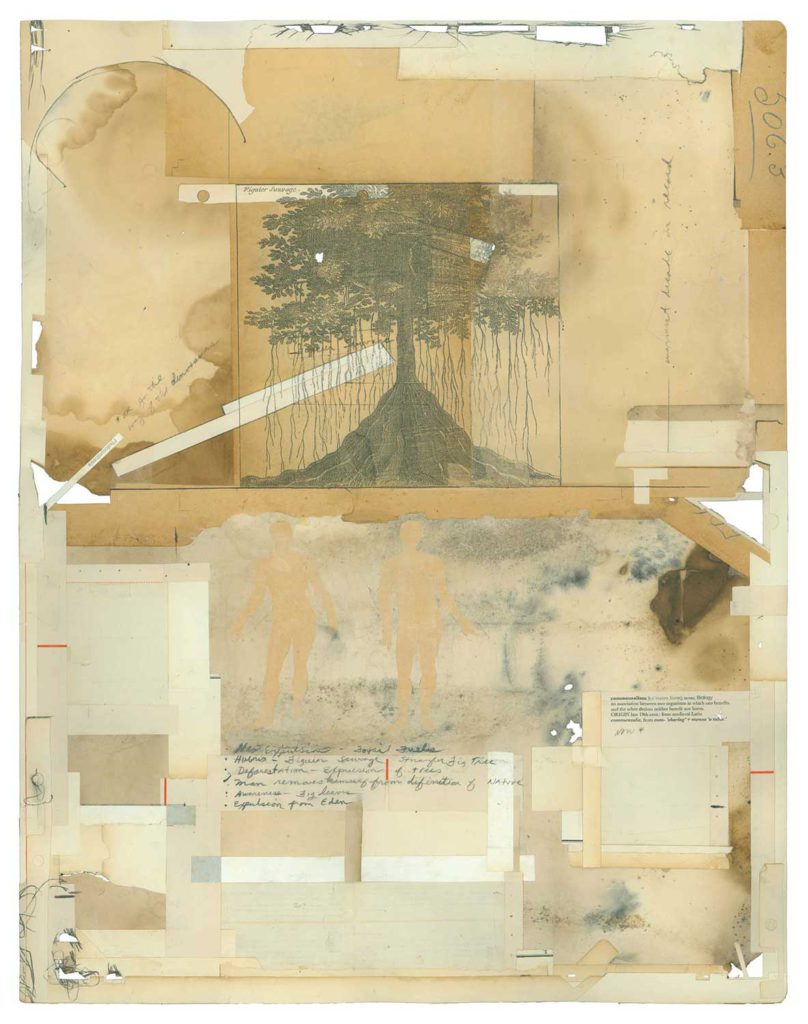

burnished, puzzle-piece fit collage, 19th century papers, end pages, marbled papers, Xerographic prints on antique end pages, toner transfers on rain eroded bulletin board papers, cancelled stamp and envelope remnant, pencil, antique cellophane tape, archival document repair tape, yes glue and dictionary definitions

24.5 x 19.125 inches

TWS – To finish, I need to ask you what we ask all interviewed people: what’s your definition of collage?

TB – ALL.

LOL, okay, here is a more down to earth answer. A collage is established by putting together two or more collected things—actual or intellectual. Anything coupled is a collage. But the type of glue used changes the temperament of that which is coupled—emotional glue is different from conceptual glue, for example. And, whatever the items are themselves, each holds histories of usage and ownership that inform the meaning of the marriage. When collage is interesting or compelling—when the marriage is lasting—it is typically because a transformation takes place in the mind of the viewer as a result of seeing and understanding the combination on several levels simultaneously. In a phrase, “one plus one equals three.” One thing plus another thing equals a third thing—a phenomenological, third thing. The third thing is the true nature of collage. My practical and cherished definition of collage is “the third thing.”

xerographic print on bond paper, vintage saw handle

11 x 20 inches