TWS –Hi Vera, please tell us something about yourself and your background

VG –I’m originally from Portugal, now living in Bergen, Norway for the past 10 years. I studied design and visual communication in both countries and today I play in the space between design and visual arts. From an early age I developed a strong relation with image making and image consumption, first through photography and concept; later hand-cut collage; and today a sort of hybrid between paper, digital, geology, design, philosophy. I also have a very strong book fetish, however, my four year old daughter doesn’t give much time for a long read.

TWS –Your statement in your website tells us that your main thing is collecting and connecting? Can you expand on this idea?

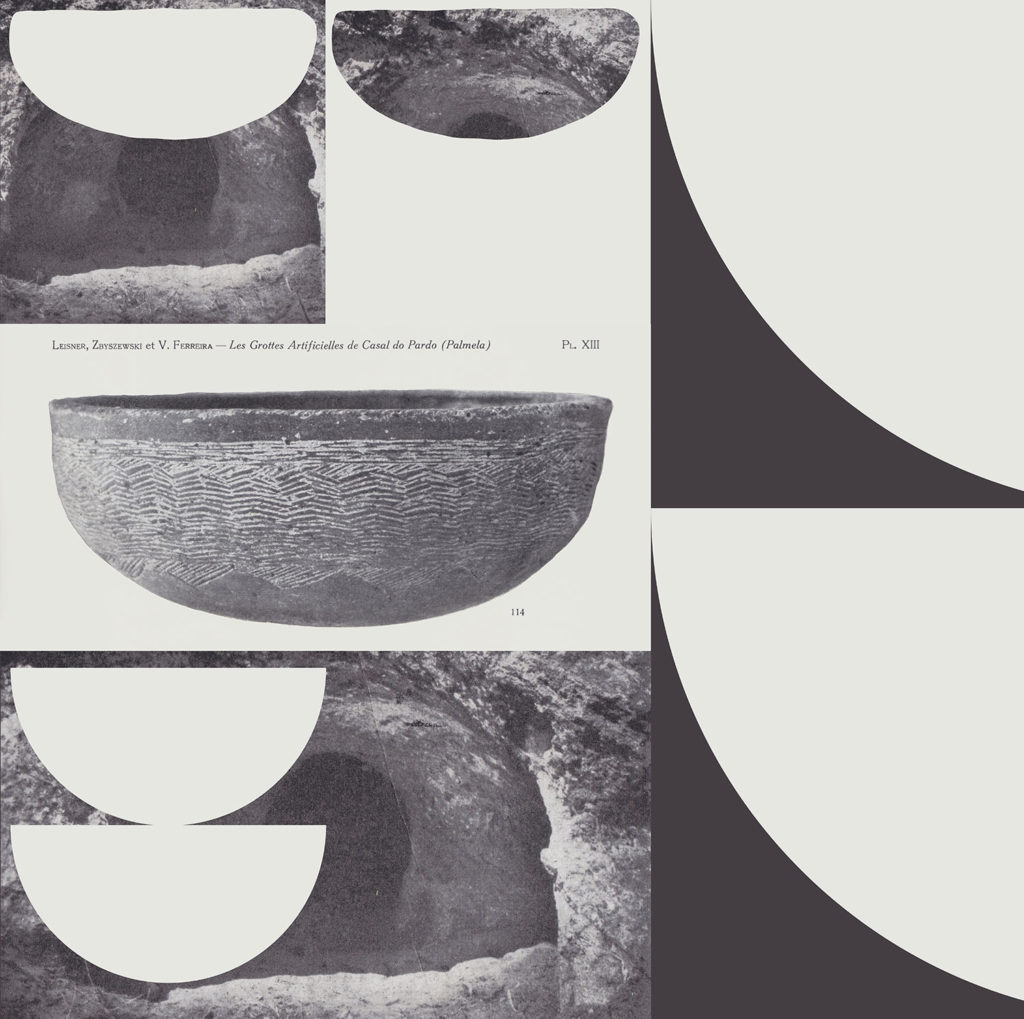

VG –Images are generally my raw material, not the things photographed, but their representations. Images as objects, with their tangibility, natural fibres and social/historical context. I start without a clear plan, as I found out early on, intuitively investigating the things that fascinate is the best process. Constantly stumbling upon new things, be they facts of the natural world or old imagery. Serendipity is an important part of the process both in the investigation phase but also during the production of work.

This sort of inquisitiveness, as a process, takes me to online archives and old bookstores, on the lookout for that perfect visual material. I also travel and photograph.

There’s a sort of organic connection between things for me, collecting and connecting is the basis of collage, be it image with image, image with text, video, concept, historical paradigms. Currently my eyes are my compass, naturally being visual-centric when it comes to decisions about my practice, though that could change.

TWS –And why you choose to work with elements such as rocks, natural monoliths, old statues and images related with our past as a planet and civilization?

VG –I’m still trying to figure that out myself, maybe spent too much time watching National Geographic or Discovery Channel as a kid.

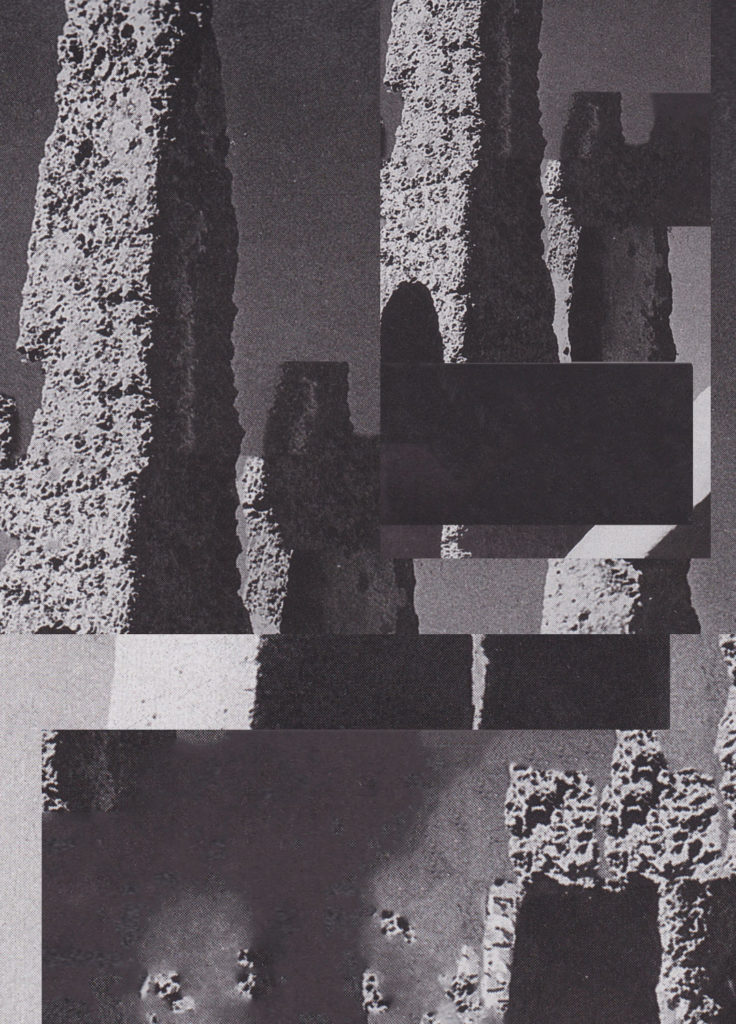

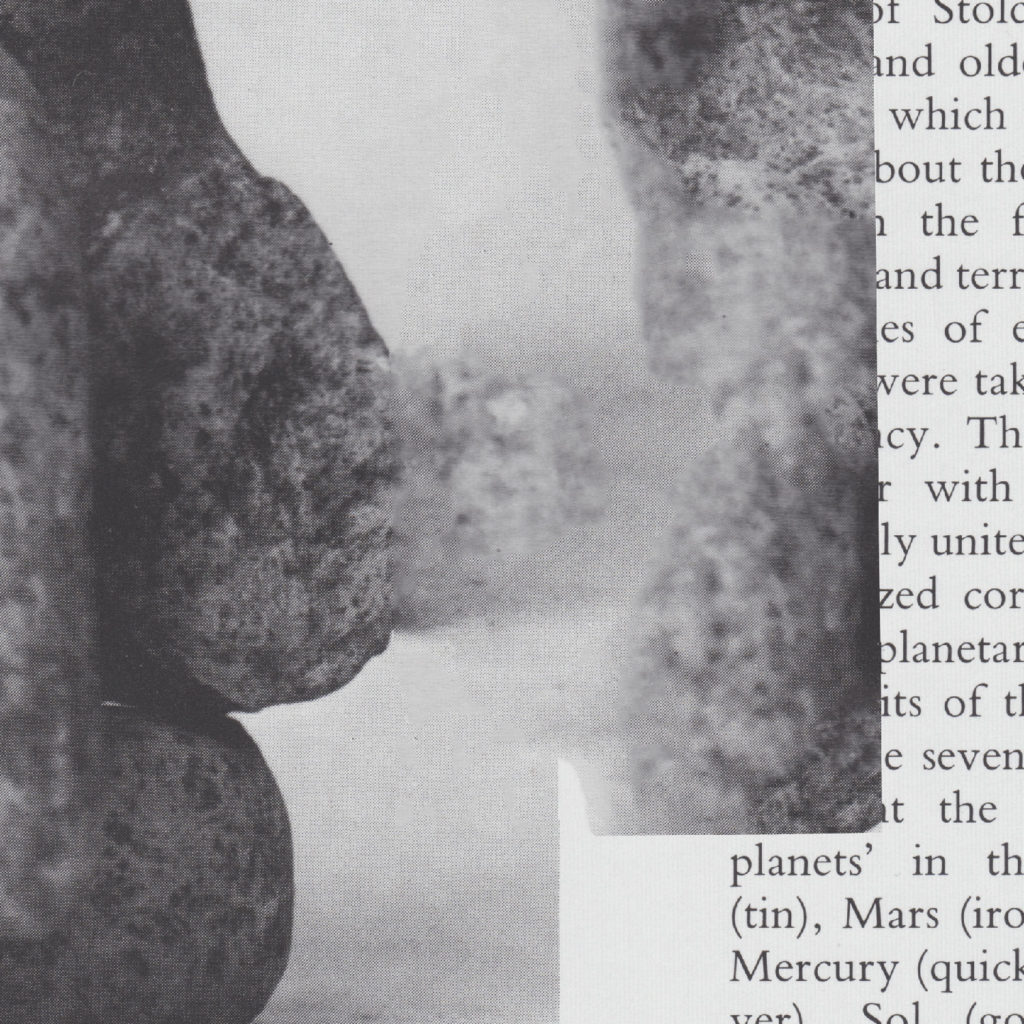

There’s something very all-compassing in rock material, minerals and geological movements. It’s a poetry in there for me, in part because rocks seem stable in our limited immediate perception, but in fact they are always on the move, always morphing in the big scale of time, sometimes with such brutality. In the end they swallow everything, in a way encapsulating time in their strata layered form, becoming testimony of the evolutionary history of life.

And then it’s also so tight with human history, how we’ve moulded it for tools and survival, for housing and temples, for art, how we’ve embedded in them the mystical and they became carriers of religion and ritual. How we mine for it, shaping landscape everywhere. And how it’s the bedrock for modern society.

It’s the stuff of the universe, it helped originate life on earth, grows in our kidneys, and now it lives inside our computers and electronics. It’s a cosmic drama.

All these narratives are a very important part of my work.

Besides, the fact that it is a fairly accessible material, because it’s literally everywhere, making it very practical and makes me a really weird person trying to document or physically collect samples everywhere I go.

WS –Your work deals in many ways with the intersections between real and virtual and interacting with digital tools. What do you look for in this kind of interaction with technology? What have you found so far working with this issue?

VG –I’ve always been largely influenced by science fiction, like the work of Aldous Huxley, and philosophy, specially Baudrillard’s Simulacra, Foucault. Recently the very relevant James Bridle, who debunks the “cloud” as a very physical thing and not an ethereal thing in the sky.

I’m interested how the virtual/media and technology influences and infiltrates in our perception of ourselves and the world. How it changes our behaviour in the offline world. The placebo effect of social media, the advent of post-truth and echo chambers, the proliferation of conspiracy theories, the religiosity and ritualistic behaviours we have with technology.

But also interested how it has very real physical consequences and seems to be the natural evolutionary step forward. There’s something vertiginous when you know that media is changing from “telling” to “experiencing” with the developments in virtual and augmented reality. The racist AI judge that will most likely sentence the person of colour, and biotechnology with all the ethics and dangers attached. The virtual and the real are no longer a dichotomy, they co-exist changing self and the collective.

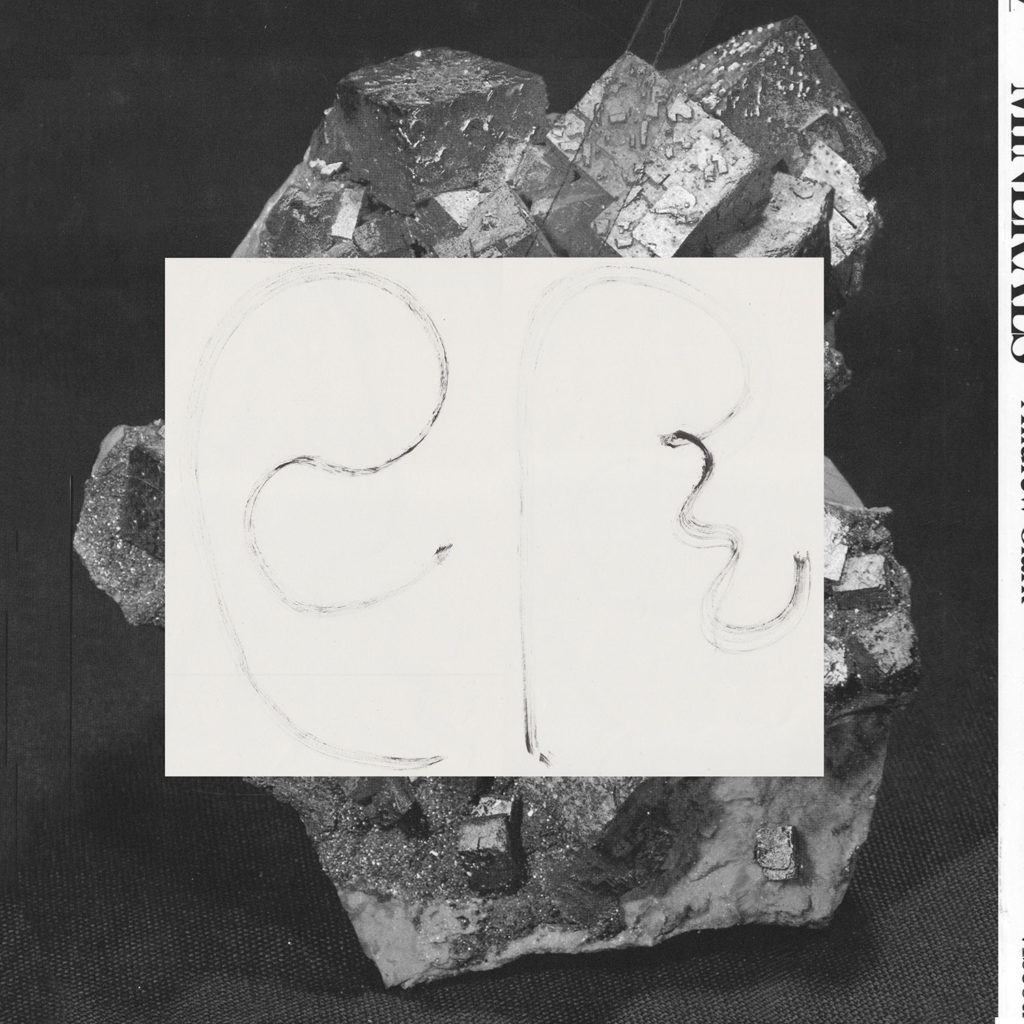

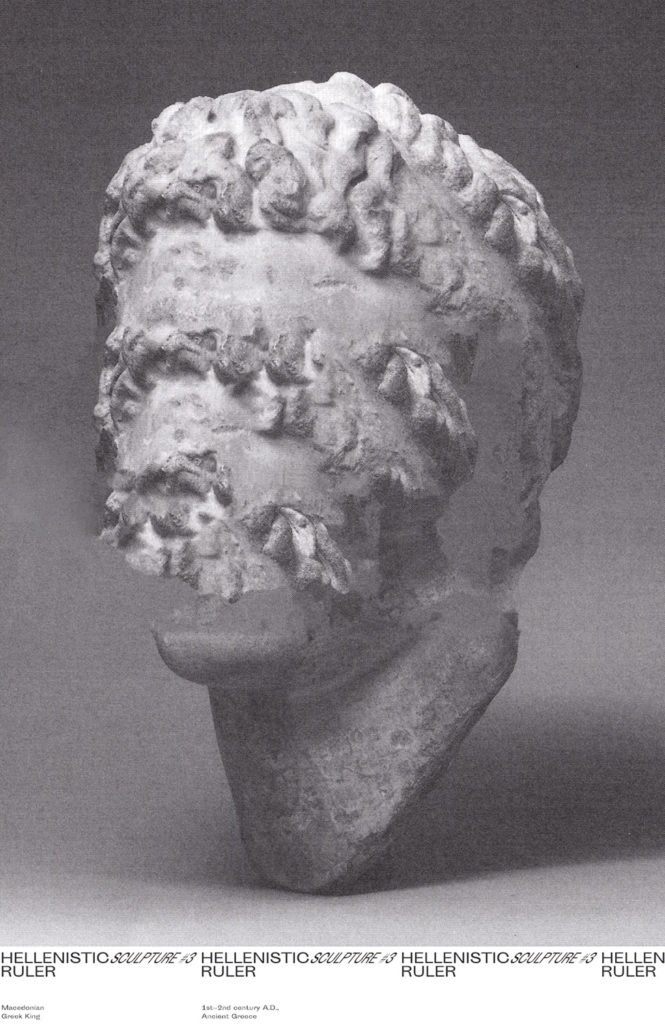

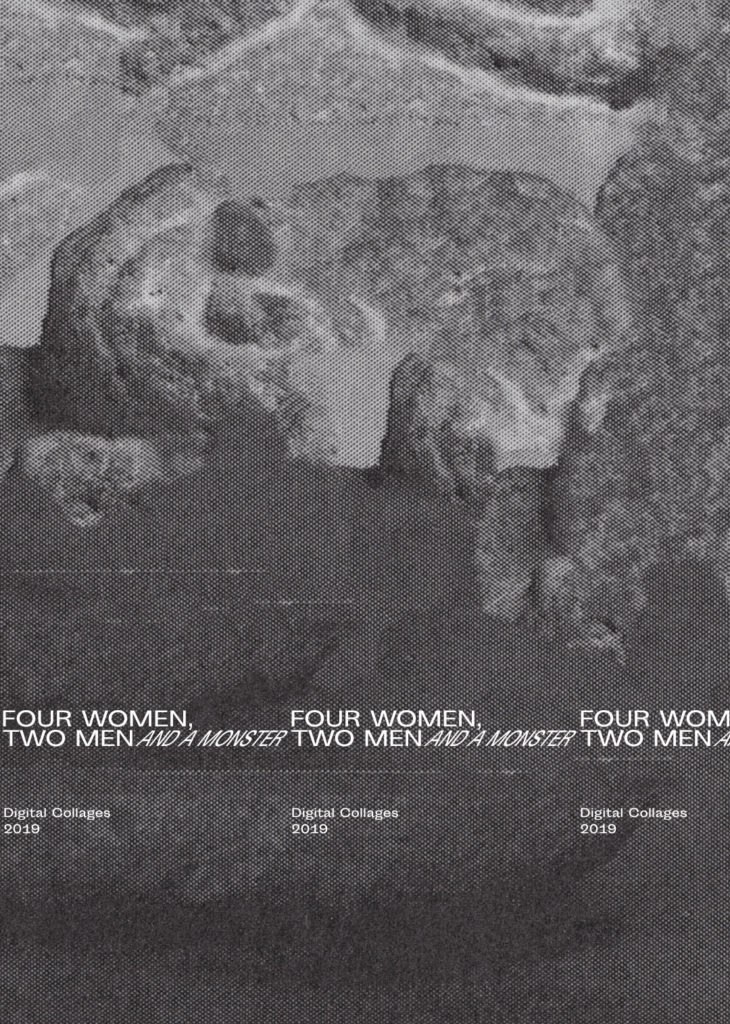

The technologic “ingredients” I use in my work serve to mimic these subjects. This is particularly true of “Four Women, Two Men and a Monster”, where I took stone sculpture as a metaphor for reality and history, and by digitally eroding them hope to provoke the idea of the digital settling down in matter, or altering the past.

I’m not a pessimist and not an expert, what I try to propose is some light reflection through speculative visual jamming.

TWS –Which is the place of glitch and error in your work?

VG –Glitch and scan art are another form of digitally intervening onto something, opening up for the random “machine’s will”. I don’t see them as errors, more like generative outputs.

I often use glitch in my analog photography, which plays on the irony of the analogue’s margin for error; you can always get the film back blank, combined with a technological mishap. Also the combination of the physicality of the analogue film and the digital glitch.

The openness for error comes also from the hand-cut collage background, where you’re working lean, with what you have, and assuming that the fortunate mistakes are integral part of the work.

TWS –Why fanzines and paper publishing is the way you often chose to show your work? How does paper closes your work’s conceptual circle?

VG –It definitely comes from my graphic design practice, making zines and small editions feels natural to me. A book with a title has a narrative, a concept, an idea, it puts a roof over all the work inside. And, when they’re printed and bound, the books are finished, so it closes down projects. I like wrapping up things, much like in the design world.

Besides, zines are a relatively cheap way of getting your work out there in a very portable and accessible format.

Though right now I see things much more in a flux and with blurry borders between projects. Currently I’m looking into making paper pulp sculptures using the paper of some of my old zines, like cannibalism, feed the old work onto the new three dimensional work.

TWS –How do you think your background and current design practice influences your personal work?

I think because of the design practice, where I’m in a constant learning curve, I tend to define frameworks around my personal work and organise projects in “bulks”, sort of like a briefing. That helps me a lot going forward. Not only that but design also makes my personal work adopt a much more graphic expression and it’s very much informed by knowledge of typography, layout and grid, means of production etc. Also this tendency of developing work as “series” might have something to do with it.

TWS –Which is your definition of collage?

VG –I see collage as a very broad thing and often use the metaphor for almost everything that is “glued” together in some intentional way. Consider it not just images, but everything, text, concept, stories. The world is so dense in images, so overpopulated, everything is sampling everything.

Combining two things together that are not usually or naturally inclined to each other, what Arthur Koestler called ‘bisociation’, completely reconfigures context, and changes the perception and meaning of each individual thing. There’s a shuffling-magic to be found when we experiment.