We talked with artist, curator, editor and writer Ric Kasini Kadour about the show he has curated with Frank Juarez at the Saint Kate Hotel in Milwaukee: The Money $how, where they discuss, through the lens of collage, about the influence of money in our contemporary culture.

TWS –The issues of money and art, that we have discussed on previous conversations, are at the core of The Money $how, the exhibition you have co-curate with Frank Juarez at the Saint Kate Hotel in Milwaukee. So I guess it is a good moment to expand on these issues.

RKK –Yeah, so I’ve been, I’ve actually been wanting to do a show about money for a long time now. And what I’m interested in is this idea that money is an idea and money is an idea that we all poorly understand and have a lot of emotional feelings about. Because of that, I think it’s easy for those in power and those with money to exert an enormous amount of influence. I think that runs through a lot of our social problems particularly in the United States, because the United States has a different relationship to money than I think the rest of the world and it flows through the history and it flows through the social discord that we’re currently experiencing. So for me, this was like, just a way to kind of unpack this idea. And so I start with the premise that money isn’t a thing. That it’s not anything that’s real. It’s this idea that humanity created as a way of exchanging and it’s supposed to be a tool of convenience; meaning, if I have bushels and bushels of wheat and you have bushels and bushels of tobacco, it’s a way to kind of exchange those things so that we work it out. Money is interesting because it only comes into play as you’re relating to an other. Meaning, villagers would not use money among each other. They would only use money when they’re exchanging and trading with other people outside the village. And then the same is true with countries and colonies and civilization, in general. That it’s only when we encounter the other, do we need money in order to exchange. So if my husband brings me a cup of coffee, I don’t tip him. I don’t pay for that coffee. It’s just part of like, you know, it’s because he’s not other, you know, we’re all in this together, but if I was at a cafe, I would, of course, pay for that coffee, because that’s other, they’re not my people.

The book starts there and then it’s really about how the different artists offer us something to unpack this idea of money. And so with your work, The Gold Rush, it was a way to talk about these boom-and-bust cycles that occur throughout history. And so, you know, there’s something going on in a place in the sense of the actual gold rushes. They find gold or silver or copper and then people rush In. And then all of this commerce sprouts out around it. And so now you have businesses, saloons, brothels, you know, all these… banks, all these essential things, to support a community and then the workers are in there, all extracting the gold, all extracting the resources and when the resources are gone, they all go away, and the town and the community die.

And this isn’t that different than what was happening in Seattle. Seattle is a city that goes through boom-and-bust cycles. So, you know, when aviation is up, Seattle’s a very hot place, and everybody is making airplanes, and then there’s a downturn in the economy. Nobody wants more airplanes and Seattle economically suffers; the tech industry moves in all of a sudden, you have a gold rush of tech and then in the 90s…We knew more Microsoft millionaires in the 90s and dotcom billionaires, millionaires in the 90s and by the early 2000s, they were completely broke. You know that boom and bust cycle, that Gold Rush thing makes for really dysfunctional communities and broken communities. And in the United States, we see it across the Midwest. We have a thing called the Rust Belt where it’s…a factory moved in, a factory brought in hundreds of workers and then there were hundreds of other people, their families., the people who ran the grocery stores and the laundromats, and the stores that supported those workers. And then the factory decided I can make it cheaper over here. And then they move and then the town dies. You see it with Walmart. Walmart moves into a town and it kills within a 30 to 40 mile radius, it kills the different communities in that area and then Walmart decides…And then that area becomes too poor to even support the Walmart and then Walmart closes. And they have literally nowhere to buy groceries. It’s this dynamic and it’s because we don’t understand the fundamentals of money.as just a tool for human exchange and how we relate to each other that we don’t think about these issues through. Does that make any sense?

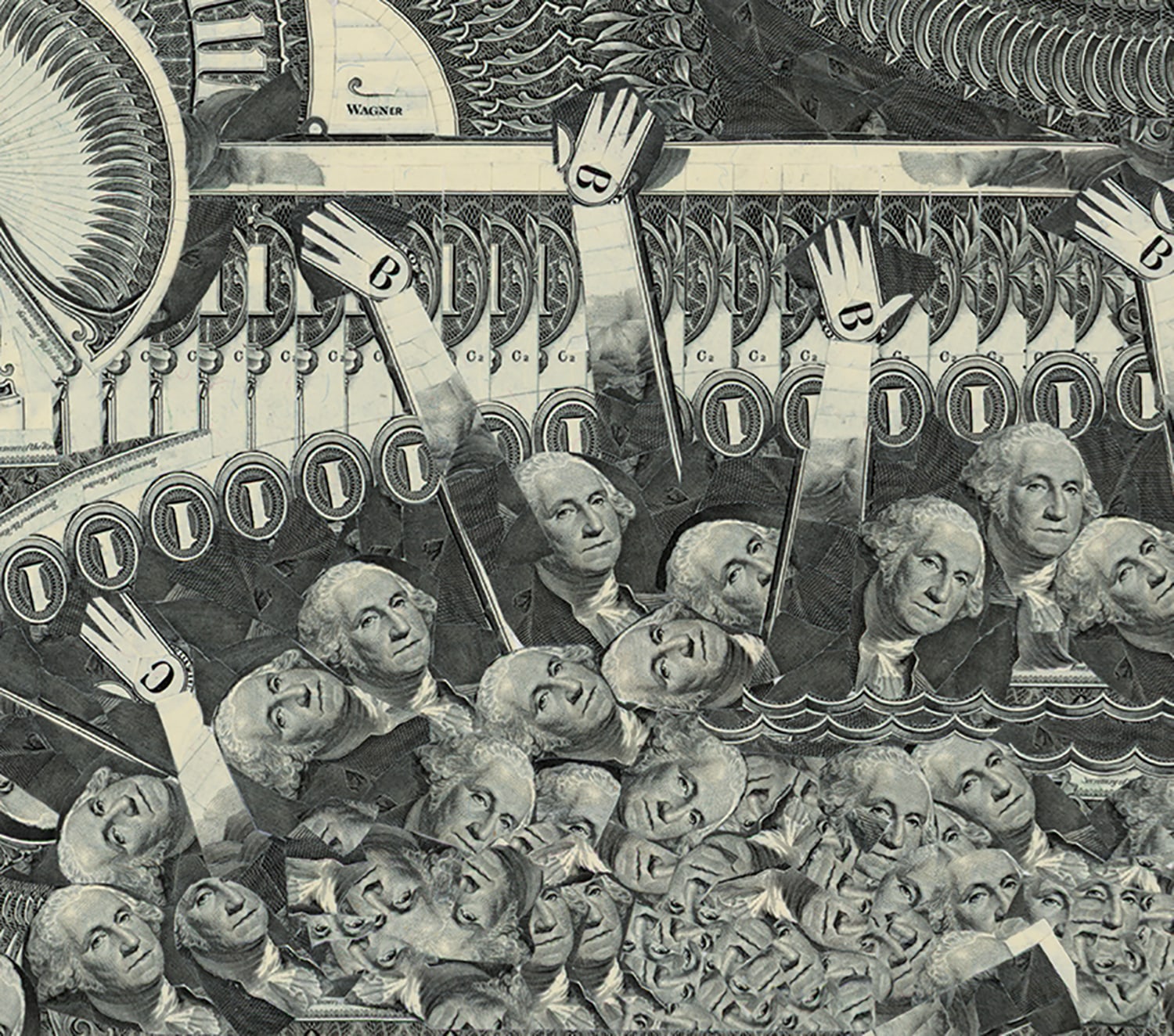

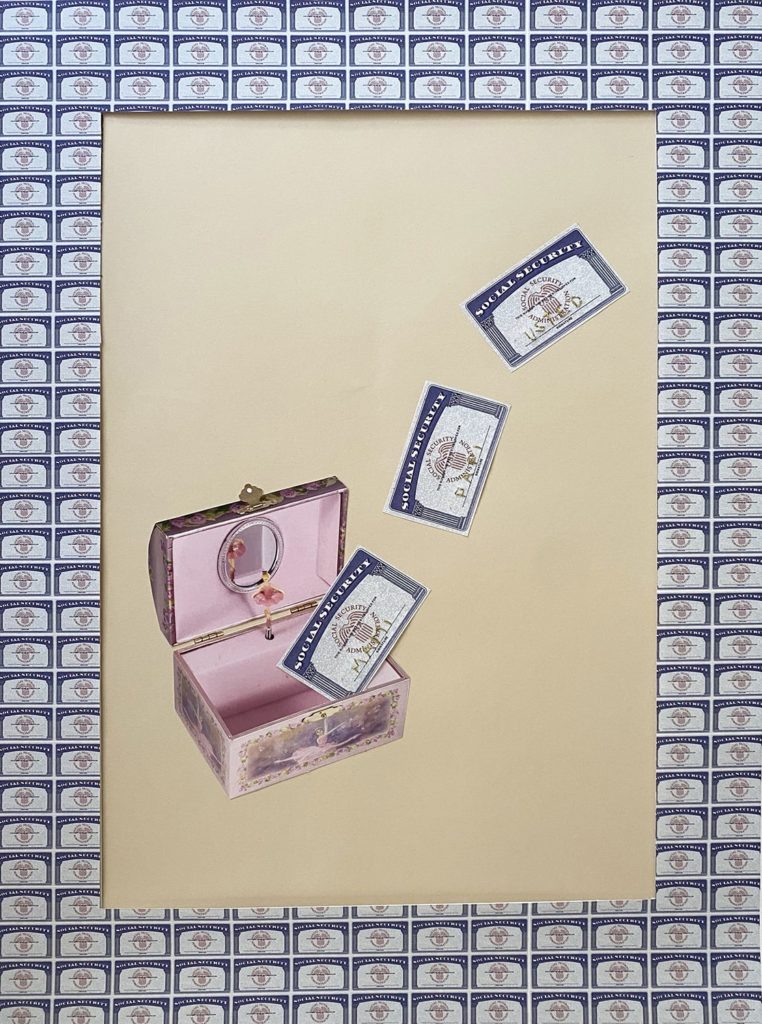

This Little Piggie or No Qualms at the Trough 40”x30”; currency on panel; 2016

TWS –But also, I think the nature of the economy right now and of late capitalism. On one hand, honey is created without being a representation of other goods or values. And on the other few people have a great amount of wealth, that make them powerful enough to be able to create the conditions for earning and accumulating more money… and power.

RKK –We live in a system where, well…I think the fundamental truth is that things are only worth what another human being will pay you for it. So, like art. The value of an art is the value of what it can be sold for. It’s similar to real estate, you know, a house is only worth what someone will pay for it, but that is filtered through much of the economy. And so a stock price is really set by what someone else will pay for it. That’s what sets the stock price. But those with a lot of money, a really easy game to play is to buy up a bunch of stock at an inflated price so that other people believe that’s the price and then, all of a sudden, the stock they already own is ultimately worth more.

There’s a scheme that happens in the art world. That this is how you take a $1,000 painting and make it a $10,000 painting. You buy ten $1,000 paintings and then you donate, because you are powerful, you can do this, one or two of those paintings to museums. Then, all of a sudden, this work is legitimized. It’s important, because it’s now owned by a museum and then you take one or two of those paintings and you put them into the secondary market, you put them up for auction. So you take them to Christie’s or Sotheby’s and you get your friend to buy one of those paintings for $10,000. And so now you have six paintings left and those six paintings are now worth $60,000 as opposed to the $6,000 you paid for them.

TWS –But you can only do that if you have money.

RKK –You can only do that if you have money and power and the thing is money will get you power, because when you make that donation to the museum it often comes with a check, you know, and you also then have the influence to suggest, hey, maybe this artist should have an exhibit for the legitimacy, you know. I think these kind of schemes run through much of our lives. There’s tons of things that we do that are designed to make a few people really wealthy. I’m thinking about to some extent health insurance in the United States because there isn’t Universal Health Insurance. You know, the fear there is one where if the United States was to move towards a Universal Health Care system like the rest of the Civilized World, there are a ton of people who will not make a lot of money off of that, where they currently make a lot of money off of that. Insurance, in general, is a form of social welfare. You have fire insurance. Thousands of people put their money in the same pot with the understanding that they will be covered if something happens to them. And then the insurance company in theory, takes a little bit of profit from that. That’s the model. Why that isn’t run by government and ultimately, for the welfare of all of the people and kind of automatic makes no sense. We’ve created these profit mechanisms that only benefit a few.

TWS –Going back to the relationship of art and money. I believe that we can divide the art world into two groups: a very small and powerful group where money is everything (Jeff Koons and artists playing in that league), and other group where art and money are almost not related (the art world were most artists find very difficult to live off of art). What do you think about it?

RKK –I also see the art world in terms of the art world and then the art market. That’s two different things. They interact and it may be when they’re at their best, they might overlap a little, but Diego Rivera in 1932 spoke to this issue. He talked about if art at the time was going to continue on this path of performing for the market, art would ultimately be treated like a commodity. I’ll share the reference and throw it in the chat.

His fear in 1932 has largely been realized by the market. A lot of work that’s sold goes into storage lockers; often in storage lockers that are located near airports in zones where they exist in a liminal space between tax jurisdictions and they live there permanently. That’s because the art then becomes a store of value, which is one of the functions of money.

But art, unlike money, we don’t tax art the way we tax money. A great way to launder money is to put something of value in an object that can be easily moved across borders and then turned back into money when it’s on the other side and that is exactly what art does. If you’re a Russian oligarch and you want to get a few million dollars into the United States, you put it into art and then you ship the art to the United States and then you sell it. Now, all of a sudden, you have all this money in the United States. You’ve gotten it out of Russia, into the US; out of Dubai and into the US; out of China and into the US. And if you look at who’s buying art, its Russian, oligarchs, affluent Chinese and affluent folks from the Middle East are largely driving a lot of these really highly overvalued purchases. We saw this with the NFT craze that’s going on right now where, you had one person spend a ridiculous amount of money on a piece of code, is it like 59 million dollars, or whatever it was, which ultimately, then completely legitimize the whole NFT phenomenon. It all of a sudden became very real. And so now, Damien Hirst is talking about issuing NFTs. Jeff Koons is issuing NFTs. What they did is they said, look, we don’t actually have to make objects, art objects to play this game we’re playing. We can just play this game with this digital code. I think this is fundamentally different than the concern of the art world and artists; at least I would like it to be. I think artists are ultimately concerned with creating an object or creating an image that ultimately speaks to their community and, perhaps, a larger community of communities and offers that personal understanding of the world or way to experience the world, and that work is not valued. We value labor because labor ultimately creates profit for someone else. We value money because the hoarding and the collection of money allows us to have power, but we don’t necessarily value deep thought, understanding, caring, culture bearing, resilience. These are things that are very difficult to commodify. Imagine if we could commodify hope; if there was a direct financial benefit to hope. There are actually researchers at the University of Vermont who study happiness and part of their argument is that happier people are more economically, stable and economically secure. Now, I disagree. I think people who are economically stable and secure and safe are ultimately happy not the other way around, but it does allow you to make that argument. Which is, Oh we can make more money if we have happier consumers. That’s where we’re at with late-stage capitalism. Everything has to be expressed in its extrinsic value, rather than in its intrinsic value.

I think art can mess with that. What’s been fun about The Money Show…The Saint Kate is a beautiful Art Boutique Hotel, with wonderful, very real galleries in it. This is not a hotel show down the corridor like these are galleries and that’s part of what they do as part of the kind of space they’ve created for themselves to work in. But it is also still a business. It is still a very legitimate real estate business. They have multiple properties. They have a hotel, they have performing arts venues and they’ve decided that the embrace of culture and the support of culture is ultimately a way for them to support their business. And I don’t think these things are against one another. I never understood why we’ve so leaned into income inequality to the point where that we’ve made it difficult for some people to just barely live. As someone who owns a business, who owns a magazine, I want everyone to be able to afford my magazine. I want everyone to have all the extra money that they need in order to pay for my magazine. Like to me, that’s just good business, you know? And if somebody can barely pay the rent or is struggling under student debt, or healthcare debt, or all these things we’ve put on people. Ultimately, they don’t have the money or the bandwidth to purchase or even enjoy my magazine. That becomes a really messed-up society and that applies to restaurants, that applies to dance clubs, that applies to everything. If we’re working just to work, if we’re not working to have a life that allows us to experience the breadth and diversity of human experience. What’s the point?

20”x16”x2”; exhibition canvas, Moab Entrada paper, lacquers, Swarovski crystals; 2020

TWS –You mentioned Saint Kate Hotel where the show is taking place. Are unconventional art venues like this (a hotel dedicated to the arts, with galleries as part of their business) something that’s happening because the art world and the art market is currently in a crisis and need a change? How do you feel about this?

RKK –I think that if you look back in terms of history, that historically, the prices of art have not really changed that much. Meaning, a good high quality painting by an established artist not engaged in the art market, not engaged that upper echelon, is usually like a thousand dollars kind of thing. And it’s ballpark, you know, a lot of factors change that. But if you go back into the into the 1940s, you know, it was about the equivalent of that much money, which is not a small purchase for a middle-class person, but not an overwhelmingly soul-crushing purchase for a middle-class person, meaning people could afford it and people had the disposable income to afford it. I think what we’re seeing now is that nobody has disposable income and there’s so much economic insecurity that the luxury of buying a piece of art is put against…Well, if I buy that painting and my car breaks down, or I get sick or all of these things…Nobody has the bandwidth for that.

You have people who have household incomes in the United States of $250,000 a year who are still struggling to make ends meet. Some of that is personal choice, but some of that is also just…it costs an enormous amount of money to live in some communities. Your rent is nine, ten thousand dollars a month. That eats up a lot of your income pretty damn fast. The market, the mid-range galleries that have been the bread and butter of artists not engaged in that upper echelon, I see them closing more and more. There are fewer and fewer galleries that are able to make a run at it simply selling artwork. I see art galleries that often have a co-business, so they’re selling artwork, but they operate a frame shop, and the frame shop covered some of the basic expenses and then the selling of art becomes adjacent to that. For an artist to say, okay I’m going to I’m going to rely on $20,000 in sales a year, 20 works at a thousand dollars. There’s and fewer galleries who can actually deliver that kind of sustained market and that’s really problematic.

Also, art is changing. Artists are not necessarily engaged in creating decorative work, pictures for one’s wall. Some of us are doing that and some of us do that in addition to other things, but I think art, as it’s playing out in museums and art centers, is becoming increasingly experiential. And that also changes the market. To sell an installation is rather difficult. It’s a very specific niche of high-end collectors or a museum. And so those of us who are creating installations or conceptual work, it becomes increasingly difficult to Market that and sell it.

I will say this though. Few artists, historically, make their living entirely from selling their artwork. Most of the time, the artists, who we think of as successful, often it’s a combination of having an art practice and also being a university professor. Different artists have negotiated it in different ways, but few artists leave grad school and then immediately start just making art and then make a living from that. Even artist practices where you have your fine art practice, but then you have your illustration practice. There’s money coming in from both and you put it together. That I think has historically been common yeah.

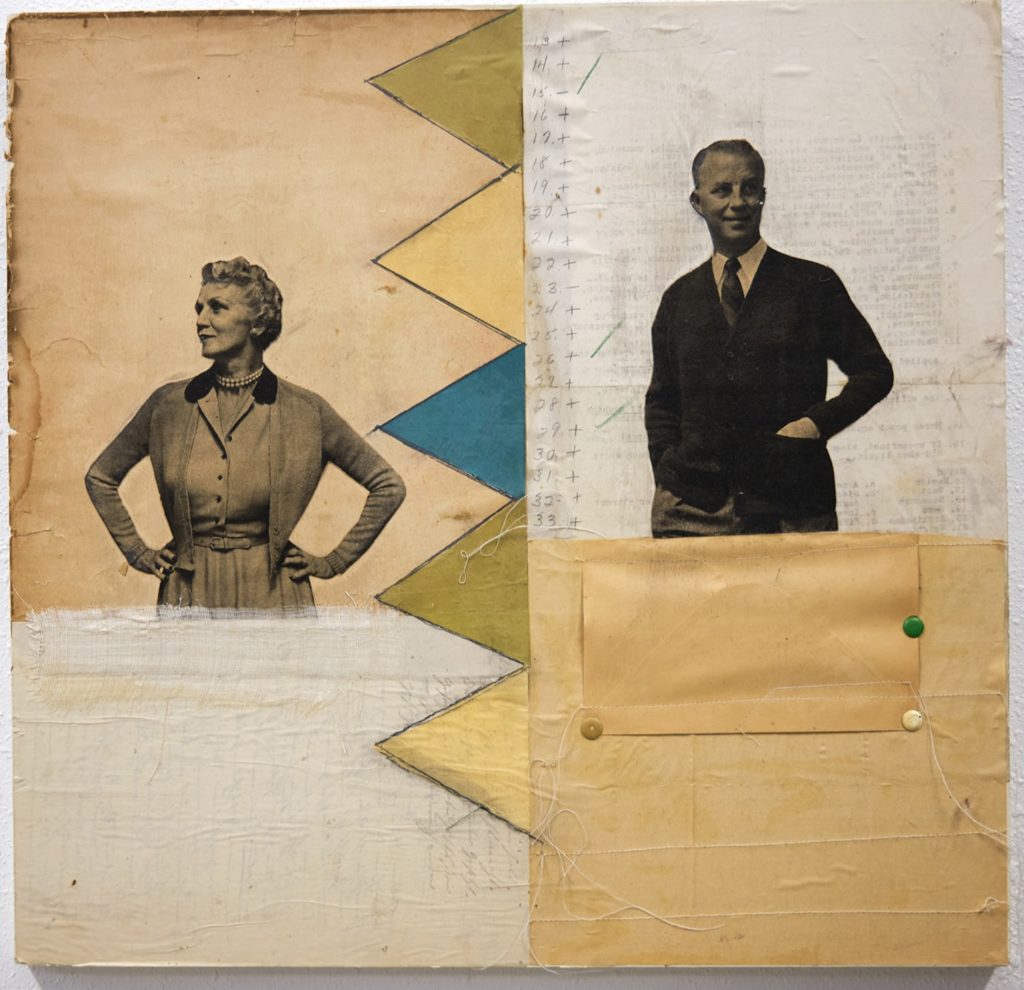

28”x20”; mixed media collage with gold thread; 2020

TWS –I have a feeling that artists are not willing to recognize this double shift. Do you feel the same, at least?

RKK –I think artists struggle to see the landscape and it’s difficult, because it’s most of us are in our community, in a single community and we’re fed a lot of mythology from other communities. New Orleans will always think that Atlanta has a better art scene and Atlanta thinks that Charleston has a better art scene and Charleston thinks New Orleans is a better art scene. We’re always comparing ourselves in ways that we shouldn’t, and we’re also not necessarily asking the fundamental questions. Part of what makes New Orleans art scene vibrant is this combination of artists who hustle and work with tourist market. So you have the artists around Jackson Square who can sell a few hundred dollar paintings in a day to the thousands of tourists that are attending that art market and then you also have a long history of some New Orleans equivalent of blue chip galleries who’ve established a collector base and also worked with that collector base to appreciate Southern art, to appreciate the art that’s actually coming from this community. As opposed to somewhere else, let’s say Dallas or Houston, where there are collectors. There are big, big art collectors in Dallas and Houston, but they’re really interested in that international art market. They’re collecting work at fairs. They’re not necessarily going to the galleries in that town and they’re interested in people who are operating in those art zones of power, who are operating out of London or Dubai or New York or LA. And that is also a different market.

It’s incredibly difficult to get a view as an artist and to also understand the reality of the business and there are artists that do and there are artists that don’t. I think every artist should go try to work for a gallery for a year to see just the reality of what it means to run a gallery and they should probably also work for a museum for a year just to see how museums operate and their decision making that they engage in. So does that answer the question?

TWS –Yes and no. I’ve got the feeling that our identity as an artist it seems that socially it’s not compatible with working in other things. It’s like if you are an artist, you have to devote your life just to make art and if you are a bartender or you are an illustrator or you paint houses, you’re not a “true artist”. And I feel that doesn’t represent how the real world is for most of the artists.We all know that almost any artist can’t live only off selling art.

RKK –But artists have always been gig workers. I mean, whether it’s commissions to do portraits or designing theater sets, or finding these other kinds of gigs that along with the sale of actual artwork, pull together an income. There’s a lot of bullshit mythology around what it means to be an artist. We should call it out as such and unpack it. The thing is, if you read the journals of artists, like and I can’t recall one right now. But I remember reading one where he talked about, oh I saw the painting this month, that’s really good, but he also talked about the other work he was doing. If you look at the actual lives of artists…Danielle Krysa’s Big Important Art Book (Now with Women), one of the things I loved about that book is it talked about that reality. They talked about, here’s an artist. She got out of art school. She started a practice, got married and ended up having kids, was a mother for 20 years and then on the other side of that, she returned to kind of art making. And now she’s been making art in this other way. It was very honest, real things. I get concerned every time an artist friend has kids, because I’m like, well, are you going to be able to sustain your practice, you know, or should I just see you in 18 years? I’m amazed at those artists that can work it out, can figure out how to make all those life realities happen. You know, we don’t have kids and that definitely allows us to do a lot of things that had had we had kids, we’d have to make completely different decisions. And the thing is we kind of dump on artist for that. We dump on that artist that hasn’t made work 10 years because they’ve been holding their life and keeping their family afloat and maybe kind of just working on things in the background or not at the pace that used to and I don’t think we should judge them for that.

In the same way that if you’re a bartender, you’re bartender. Bartending is a great way to like boom, make a bunch of money. Spend your days doing your art. We deal with this in the Artist Labs that we’ve been running. One of our rules for the, for the lab is that as it relates to the lab, they’re artists first, that this is a space where it’s like, okay, I’m going to be an artist first and I’m going to worry about my other life obligations second for a moment and it can be incredibly difficult for artists to have that space. I think that’s where artist residencies are incredibly valuable, where you can go and spend a sustained week or two or three or longer just focusing on the art as the first and foremost thing. It doesn’t mean you have to give up on the rest of your life, but I think it helps to say, “This is an art day,”

18”x18”; mixed media on vintage paper; 2016

TWS –I feel that the idea of what is success is something that it is also important here. It seems that if you are a bartender and an artist, but you have your own voice and you have expressed all the ideas that you want to put out through your work, you’re not as successful as if you have a steady income selling whatever you sell. It’s what you said about the mythology of what it is to be an artist and what needs to happen to be a real artist. And I think reality is far from that mythology.

RKK –And not only that, but I think we should…I’ve never read the history of an artist where the history was, how much they sold. That’s a factor of the media. Our current media reports on art and how much it sells for. Jeff Koons is considered an important artist because of the price of his work. Banksy is an important street artist because of the price of his work. That’s the message we get in the media. And I think history is not kind to that. There were tons of artists who were huge sellers in the 19th century and we don’t even remember their names anymore. I think it’s much more important to be good at your practice. I think it’s important to be engaged in the art world, meaning not just as a maker and sometimes exhibitor, but someone who is actually kind of a part of that scene, We make the work we make, if we make it to sell it and there’s nothing wrong with making work to sell it. But I think making work only to sell it only to fit that market, really shuts us down. And there’s a whole bunch of other opportunities to make things and engage with humanity, other than a simple sales transaction. Those people who only make work to sell great, God bless him, go do it.

It can be incredibly limiting in terms of what you’re doing. I think it’s better to cultivate a reputation, to put ideas out there, to bring communities together. I think there are all these other different modes of operation than simple sales and hopefully within those different modes of operation, there’s also opportunity to make a living, because that’s the other piece.

TWS –Taking some distance from money seems a nice way of putting art into an interesting place again.

RKK –Well, you’ve talked about creating experiences, this idea of creating experiential space, and that’s the thing, sometimes, the biggest, baddest idea we have is, like, I just want a room and I want musicians and poets and art and we’re just going to create this scene, this party that people go and they’ll experience this thing and maybe we’ll do that over the course of a week, maybe it will just be one night. And then the question becomes how do you pay for it? How do you pay for it and…often failed…need to be entrepreneurial. The thing about being an entrepreneur is it’s a combination of failing, failing, failing like failing upwards, but also just solving the next detail, breaking it down to. Okay, how are we going to rent a room? How are we going to make revenue from this to afford the rent? Do we get a sponsorship? Do we charge tickets? What are the different paths and strategies we have to do that and then you just work it and you fail and you fail and you fail and then eventually it works.

TWS –It’s more using the money as a medium to get what you really want and not having the money as the goal of your art.

RKK –Right. Money is efficacy, but money is just the ability to do things.

TWS –The ability to make things happen.

RKK –It’s interesting. That’s one of the things that sets the wealthy apart from the rest of us. The wealthy understand at a certain point…There’s two things: one is you have enough money. You’re at a point where you don’t need to sell your labor to someone else.

Right. That’s number one, like a threshold and that number is probably between three and five million dollars depending on your lifestyle. Because once you have like three to five million dollars, ultimately the interest generated from that is enough for one to live on. The more you have, the better you can live, never touching the principal. The wealthy understand that, but then when you move into the uber wealthy, what they start realizing is, oh if I had 200 million dollars, now can make things happen. I can buy this real estate, I can employ these people, I can do more things. They’re thinking of money as efficacy. The reason Jeff Bezos wants more billions of dollars is because it’s more efficacy. He has so many billions of dollars, he can’t comprehend what to do with it all, and he just split half of it with his now ex-wife, right? And he still has all of these billions of dollars. Watching his ex-wife, MacKenzie Scott, she’s giving it away. She’s using it as efficacy. She’s going, Okay, this organization does good work. Here’s a million dollars. This organization does work, here’s $500,000. She’s just trying to make things happen in the world and it’s that money is efficacy at that point. The thing is, we have this in our own world as well. Like, you know, we get a grant and all of a sudden, you know, we can do things that we couldn’t do before. But so many of us are trapped in this realm of. How do I sell my labor to someone else so that I have the basic amount of money to live? Artists are trying to figure out a different way, which is how do we get the money that we need in order to have the time to do what we do as artists? It’s a slightly different question.

I’ve been deep into this stuff for the last six months. I’ve been thinking about it, thinking about it, thinking about it.

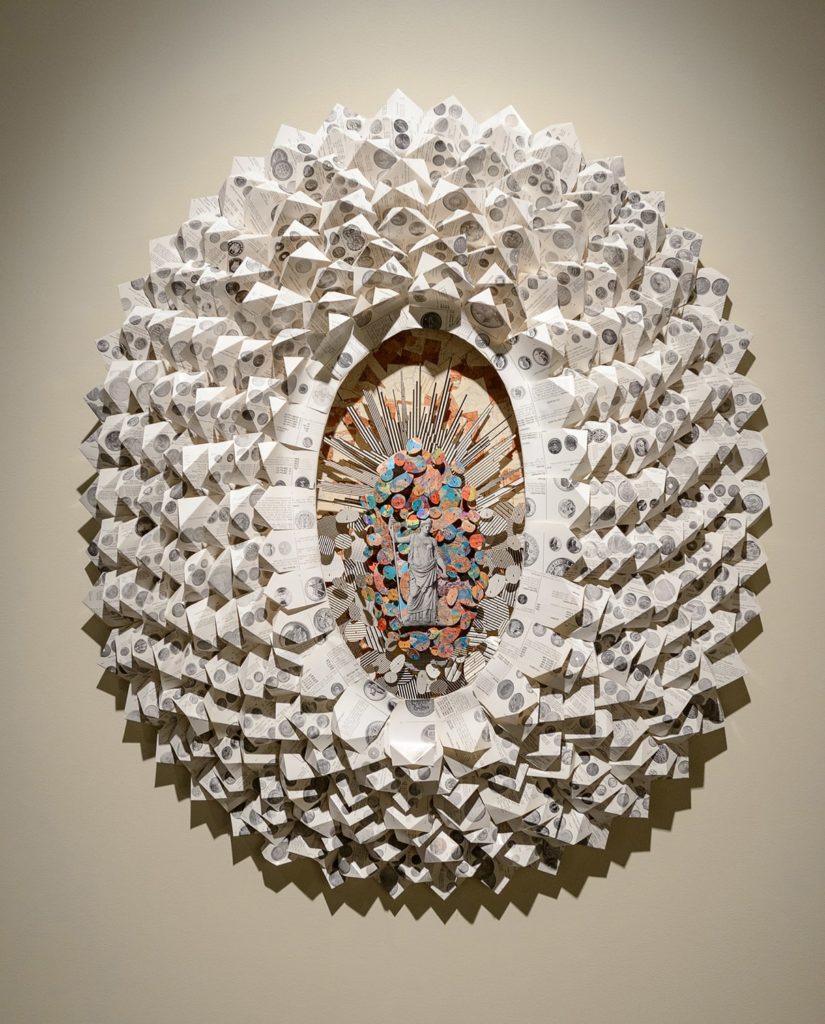

48”x36”; marbled and folded found paper; 2014

TWS –Going back to the exhibition… can you tell me about the idea behind the selection of artists that you made and what was the story you wanted to tell in the show?

RKK –The story of the show as a whole is really the one that money is an idea and that money impacts us in a lot of different ways. And so in looking for artists, what we did is we, Frank Juarez, my co-curator and I, we started for collage artists that we thought there was there were elements of their work that we could pick up on and connect to this other idea and story.

I’m into this idea and some of the work I’m doing as the Warhol Curatorial Fellow is really about, how do we see art space as being the Public Square, as being the place where we can have our civic discourse and talk about these issues. And so in looking at artwork. I became really interested in. How can we take this work and connect it to contemporary issues; to use it to talk about things that are going on in the world. Patricia Leeds is an example of someone who’s using the history of advertising as a way of unpacking white supremacy and understanding how white supremacy has been marketed to us and deconstructing a sense of whiteness. In the book, I end up talking a lot about the history of Pears’ Soap, which is this brand of soap, that was essentially, The Whiter you are the better you are. They used a lot of very racial imagery to underscore that point. And in the whole existence of that soap, it actually started in the UK. I’m going to go on a brief tangent, where the lighter you were meant the less worked in the sun, meaning you were wealthier because you were paler and then that got translated into America, which is the whiter you were, the more civilized you were, the more pure you were, the more American you were and so she’s giving us these advertisements, that is really asking us to think about what other things are being marketed to us as consumers and what other values are there.

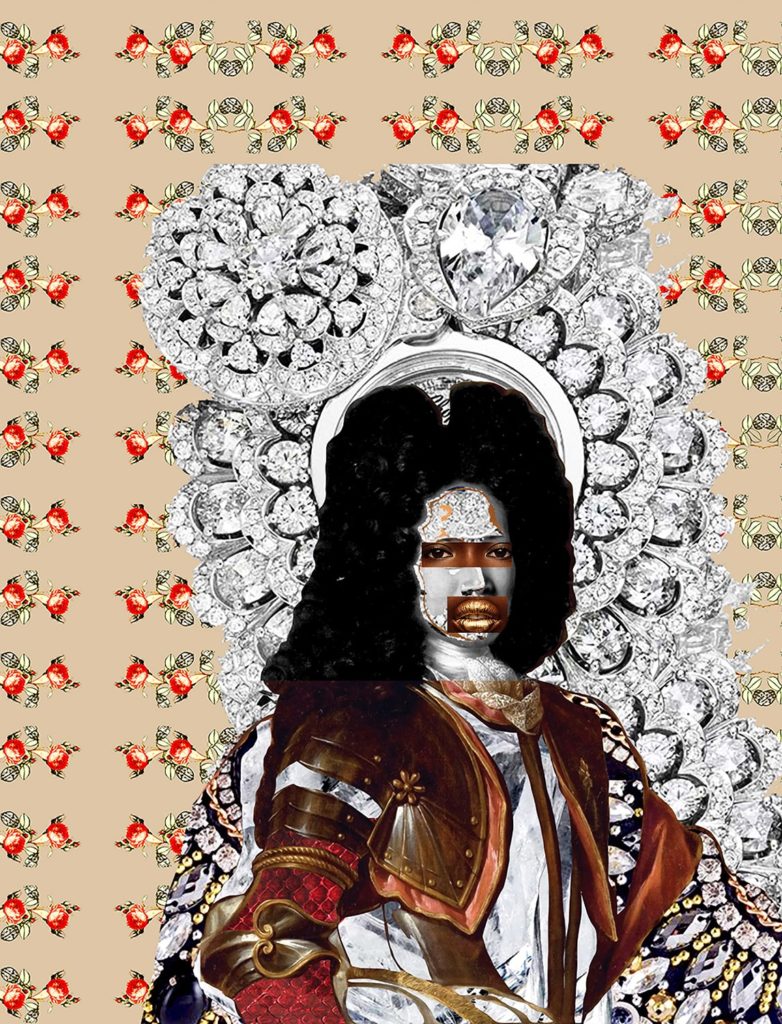

By contrast, Carey Watters is creating shrines, these reliquaries, imagine a collage that is also like an altar and in one of them she’s using the background is all bidi paper, wrapped in Indian bidi cigarettes and so it’s an opportunity then to talk about tobacco as currency, but also commodity currencies in general and it’s also an opportunity to talk about the cottage industry of the bidi rollers in India and how small industry operates and takes place. And then she has another work called Tribute. I might be flipping the two, that is really looking at how money is magic. That there’s aspects of money that are magic and we can use that then to also unpack money as religion. And so in the book a lot of what I do is I have presented this work in juxtaposition with a lot of historic images. There’s this one fantastic image of a cathedral with a giant illuminated dollar sign and it comes from Puck magazine, a late19th century magazine that did a lot of satire and parody, but it was calling out, the cult of money that seemed to have been taking place in America at that time. We’re always kind of dealing with these issues. Each of the artists, we kind of give that treatment to. Gavin Benjamin’s “Heads of State” are really about imagining black wealth. And so we juxtapose that with some history of black wealth and how black wealth is also often under attack and being undermined in American society. In some ways, the show is very American that way. I think these issues play out in Europe, but they play out in a completely different way and with a different history.

In addition to the exhibition, we’ve got World Collage Day coming up. So they’re going to do an event at the gallery for World Collage Day. We’ve got Frank Juarez, the editor of Artdose, which is a Wisconsin-based magazine. In June we created a collage residency. One of the books I used to talk about Teri Leicht’s work in the show. Teri Leicht is all about early 20th century material culture and there’s this fantastic book by Eleanor Porter called Oh, Money! Money!. What we’ve done is created a residency where we’re going to bring collage artist together to illustrate that book and then Kolaj Institute will publish that book and then at the end of July will do a Kolaj LIVE. We think. We’re waiting to see where COVID’s at, but in the next week or two maybe we’re going to announce that we’re going to have a collage live event over a weekend in Milwaukee at the end of July. We’re just waiting to see where everything is. We’re like half pandemic now. It’s okay, but not okay. Get vaccinated, wear your mask. But I think we can travel a little more and be in a room together, which would be nice. I’m tired of zooming. The book will be out probably third week of May. And that’s a big hundred page book, with not only the images of the artwork, but also dozens of historical images that we hope inform the work. This is how I’m approaching exhibitions moving forward: There’s the exhibition in the space, but there’s also the book and the book can go a lot deeper on some of these issues, provide a lot more commentary. There’s about 6,000 words of gallery text, but there’s 35 thousand words in the book. You can just go a little bit further. What’s been great it is hearing stories from the Saint Kate about how engaged people are with this exhibit and Sam talks about them talking about these ideas. She overhears conversations around the things we raised in the exhibit.

TWS –Good reception for the people that are visiting the exhibition is what’s all about, I guess.

RKK –That’s what it’s about, right?

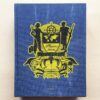

Max-o-matic, Gold Rush, video animation, 2020

TWS –Putting some ideas out and having people interested in those ideas.

RKK –That’s the next thing I’m really interested in. With this research in this Warhol project I’m doing, it’s all about how do you get people talking to each other in an art space? I go to the museum and I never talk to other people going to the museum. I don’t meet people when I go to the museum. It’s this weird solitary experience. I’d like it to be a bit more dialogic. I’d like to make it a little bit more interactive and hear what other people think.

TWS –Museums and big art spaces, at least from what I see are related with silence, with contemplation. They are some kind of church, where you have to bow to the masters and receive the “light of art”…

RKK –On this New Mexico trip, I’m going to this place called The Harwood Library in Taos. No, it’s the Harwood Museum in Taos, but it used to be the Harwood Library and Museum. It was built 80 years ago or so, and it was a library and a museum. There was art, books, art, books, all integrated together. And the wealthy people who were on the board of this institution, got tired of the people coming in and getting in the way of their art. So they got the city to build a library and they moved the library out. And here they are 10 years later going, Why doesn’t anyone come to the museum? It used to be a real hub of the community and it stopped being that the moment it just became a museum. Because it went from being a community space, a Public Square, a library to being a temple and it was a temple, it was a church. Not a fun Church.

More about the show:

The Money $how.

Curated by Frank Juarez & Ric Kasini Kadour

April 10–August 10, 2021

AIR Space

Saint Kate – The Arts Hotel 139 E Kilbourn Ave Milwaukee, WI 53202

www.saintkatearts.com

Featured artists:

Gavin Benjamin (Pittsburgh, PA), Mark Wagner (Lancaster, PA), Patricia Leeds (San Rafael, CA), Carey Watters (Milwaukee, WI), Paola De la Calle (San Francisco, CA), Terie Leicht (Fredonia, WI), Max-o-matic (Barcelona, Spain), Michael Koppa (Viroqua, WI)

The Money Show” in the AIR Space of Saint Kate – The Arts Hotel takes guests on a tour of late-stage capitalism. Each artist in the exhibition uses collage to unpack ideas about money and its influence on our culture. Artworks speak about Black wealth, immigrant remittances, and how mid-20th century advertising informs present-day attitudes. Artists collage dollar bills into flowers and mine material remnants to tell stories about home economics. The exhibition is co-curated by Frank Juarez, the publisher of Artdose Magazine, and Ric Kasini Kadour, the editor of Kolaj Magazine.

The curators start from the premise that money is an idea that shapes contemporary life and present works that invite viewers to consider cash, labor, and capital. “To speak about money without using cliches is nearly impossible. It makes the world go round. Another day, another dollar. Worth its weight in gold. And so on. Money is ultimately an idea. A symbol of value we can use to exchange goods and services. Money is capital and debt, something to save and something to spend. In this sense, it is a fundamental part of humanity. At its best, a crisp ten dollar bill inside a birthday card from one’s grandmother, it is delightful. At its worst, it is an excuse for deep cruelty, a permission to allow suffering to go unaddressed. At the beginning of the 21st century, late-stage capitalism has allowed money to become a powerful social force that influences nearly every aspect of our lives,” says Curator Ric Kasini Kadour.

Featured artists are Max-o-matic (Barcelona, Spain), Michael Koppa (Viroqua, WI), Gavin Benjamin (Pittsburgh, PA), Mark Wagner (Lancaster, PA), Patricia Leeds (San Rafael, CA), Carey Watters (Milwaukee, WI), Paola De la Calle (San Francisco, CA), and Terie Leicht (Fredonia, WI).

In addition to the exhibition, Saint Kate – The Arts Hotel will host a series of events. On April 17, 2021, as part of Gallery Night MKE, the hotel will host the curators in a virtual talk. In celebration of World Collage Day on May 8, 2021, Saint Kate Curator Samantha Timm will lead tours of the exhibition. On May 22, 2021, exhibition co-curator Frank Juarez will host the Artdose Social Club in the gallery. On July 17, 2021, the gallery will host a Kolaj Magazine Meet-up. Kolaj Magazine will publish a book to accompany the exhibition that will be re- leased in May 2021.

For full event announcements, follow Saint Kate – The Arts Hotel, Artdose Magazine, and Kolaj Magazine on social media.