It’s not an easy task to track down Cless. About 4 or 5 years ago, I sent him several questions for an interview, and he never responded. I understand—these things are difficult for him because his work, his ideas, and his actions form a complex whole where there’s no room for chance or lightness. Where others might see chaos and free improvisation in his work, he creates perfect symphonies where every element has a purpose. I imagine he expects the same from interviews: nothing left to chance.

Nonetheless, 5 years later, I sent him new questions for an interview. And, after some friendly but persistent nudging, he responded exactly as you’ll see below. Ladies and gentlemen: Cless.

TWS – Tell us something you’d like people who read this to know about you.

C – Hi, I’m Cless, nice to meet you! It’s a bit complicated, but here we go! You’re still in time to stop reading! Thank you.

TWS – What is the earliest time you remember that a piece of art or graphic work caught your attention?

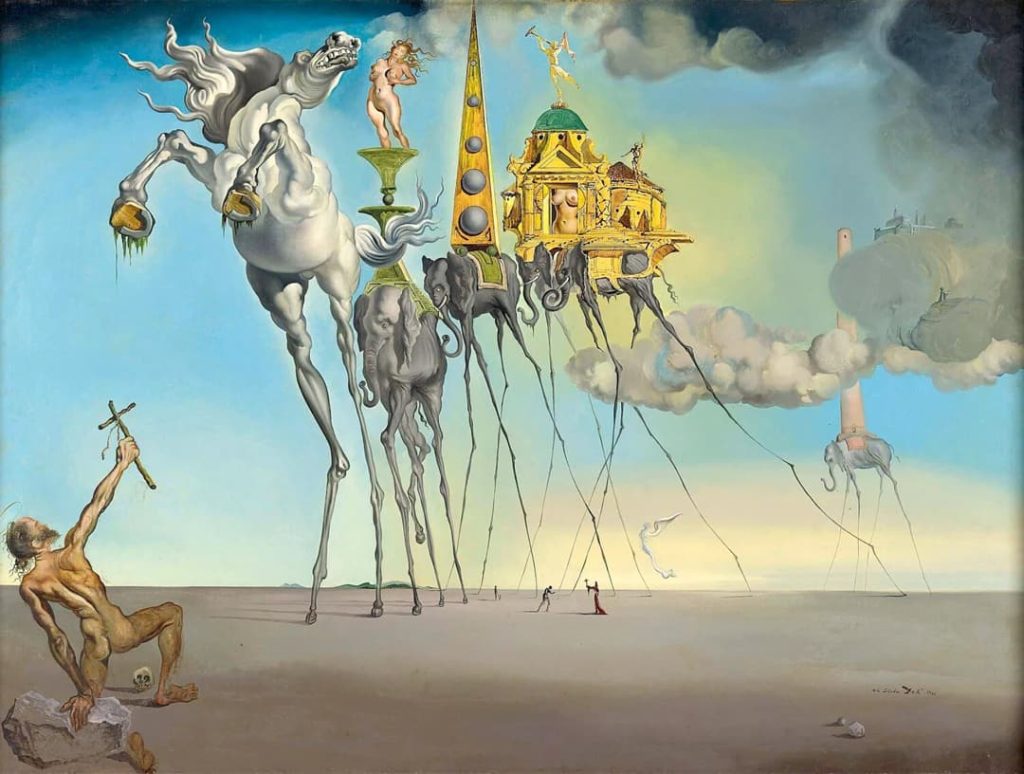

C – I was very young, about four years old. I was playing under the big dining room table with some wood pieces and a pen. I told my mother, who was in the kitchen: “Mom, when I grow up, I’m going to be a Picasso.” My brother bought a framed poster of Picasso’s Guernica and hung it on the dining room wall. I’m not sure if it was the first piece that caught my attention, but maybe seeing it every day subliminally engraved the code in me. I also remember another painting by Dalí, The Temptation of Saint Anthony. I have a vivid memory of those elephants with their exaggeratedly long legs; I was fascinated by that piece.

TWS – Choose 3 artworks or graphic pieces that have influenced you in becoming the artist you are today.

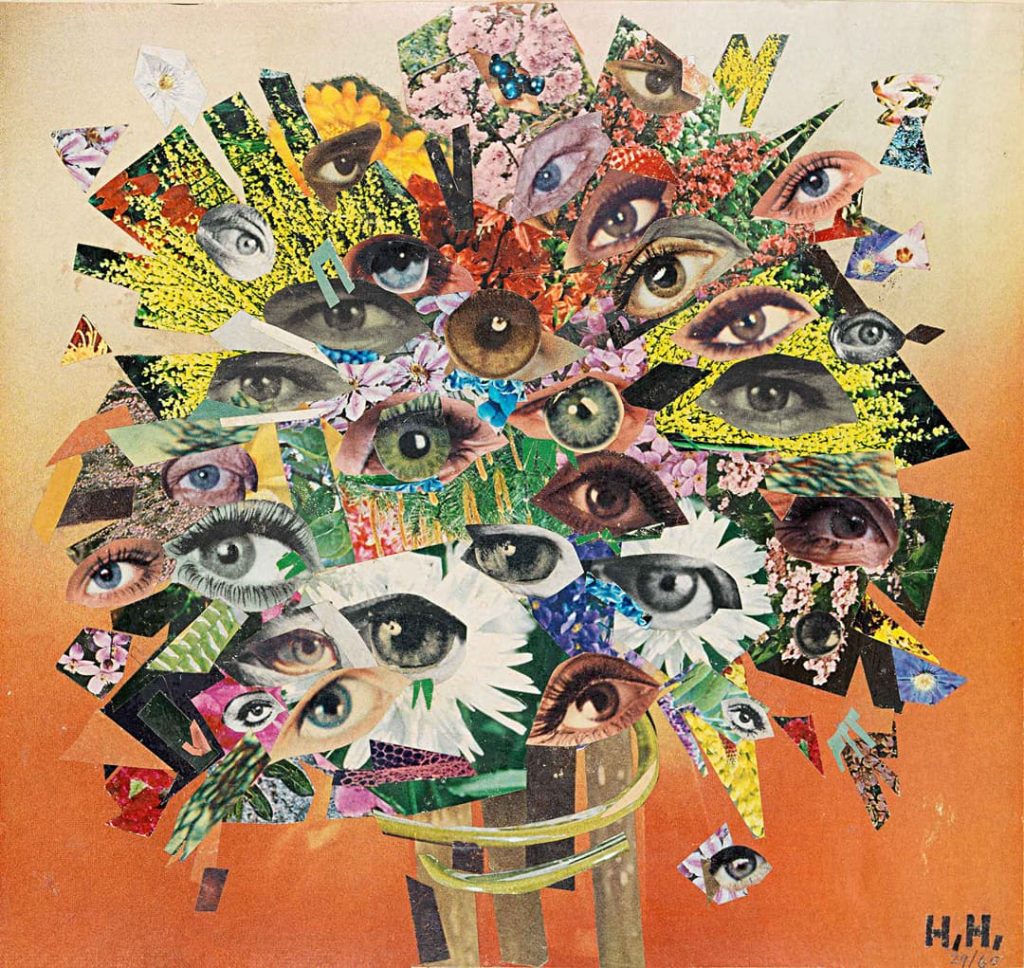

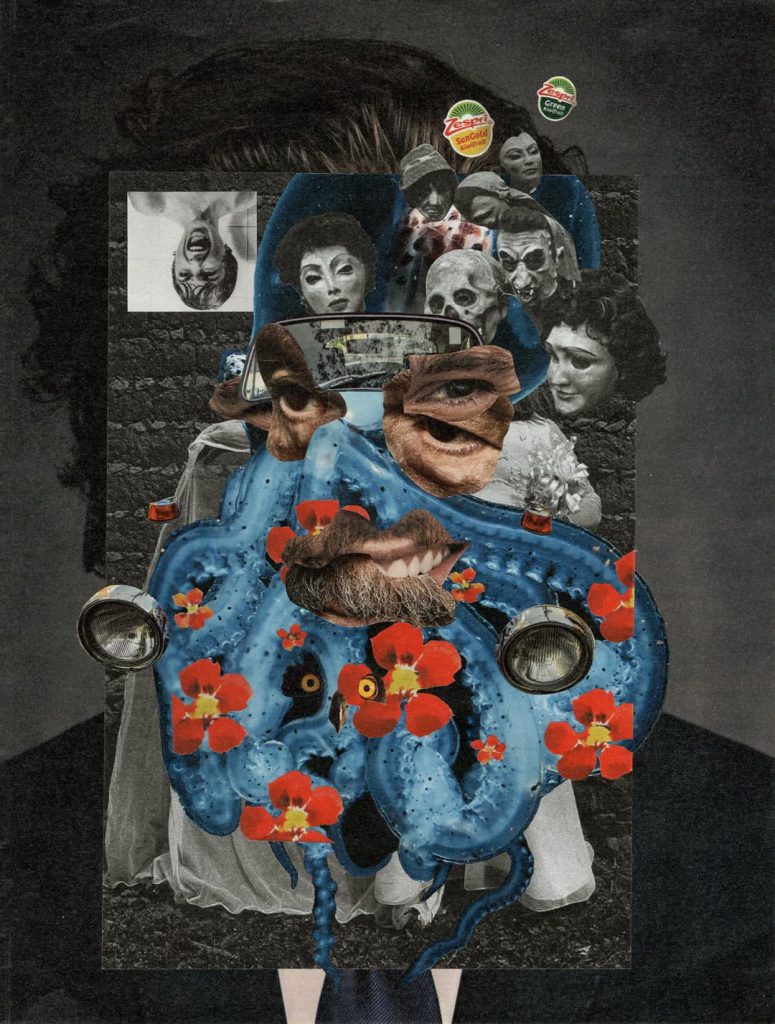

C – – Hannah Höch – Der Strauss. Bäst – His work in general. Francis Bacon – His work in general

TWS – Tell us about your first contact with art. What caught your attention early in life?

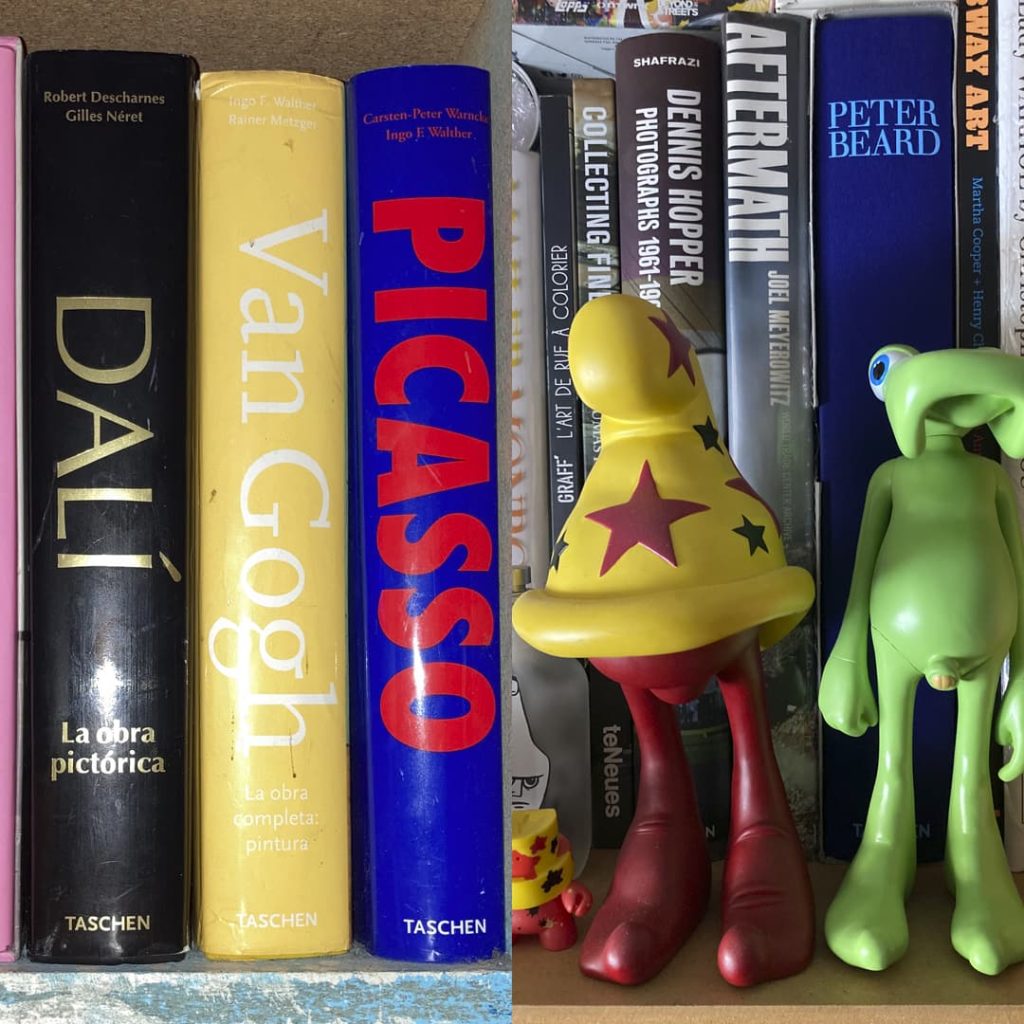

C – My introduction to art came through my brother Nane. We slept in the same room. I was a kid and had to go to bed early. Since I didn’t want to sleep so early, I entertained myself with the art books my brother had in the room. That’s where it all started, with Dalí, Van Gogh and Picasso. I think my passion for art and collecting books started with him. He had a lot of books and would tell me about artists, explaining fascinating details. Also, when I was little, my father took me to almost every museum in the city. That could have been the start of my path into the art world. From there, I started exploring and creating my own references, and soon after, I got into graffiti and design.

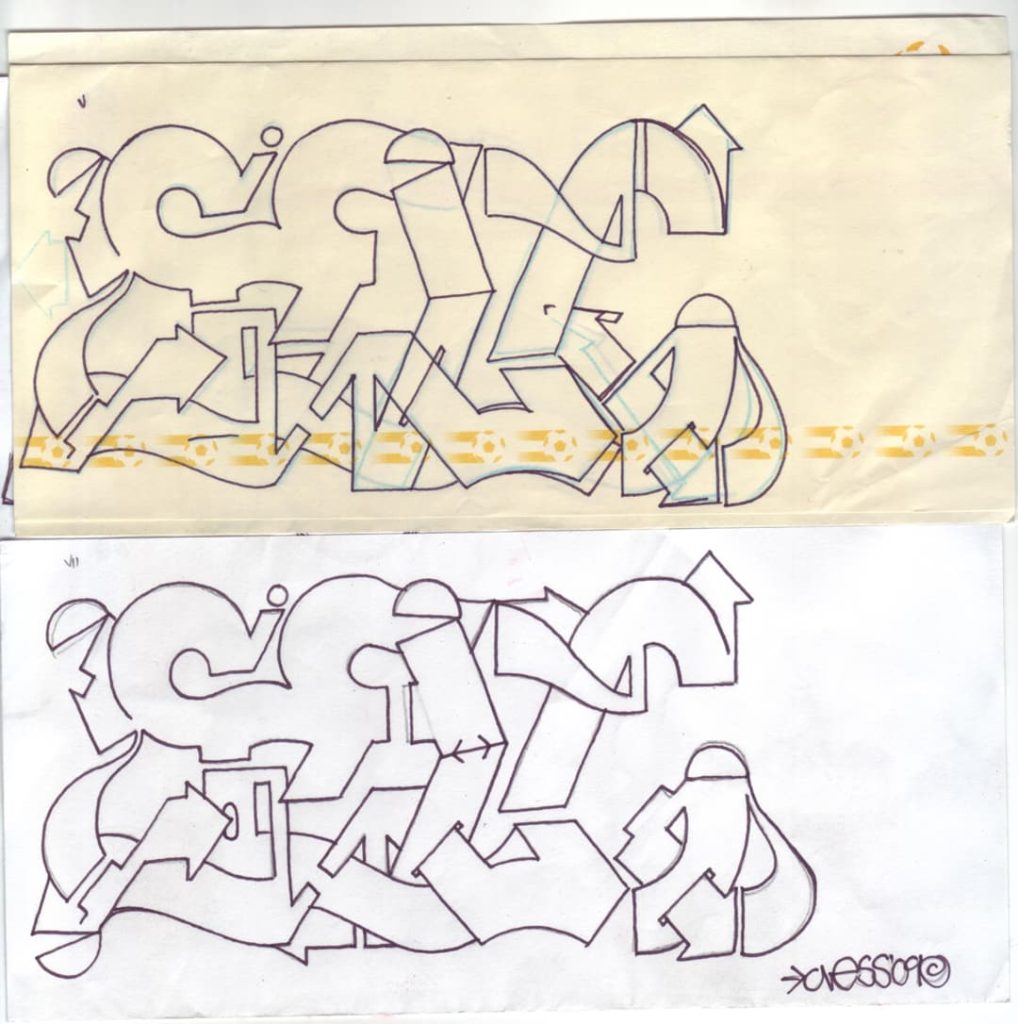

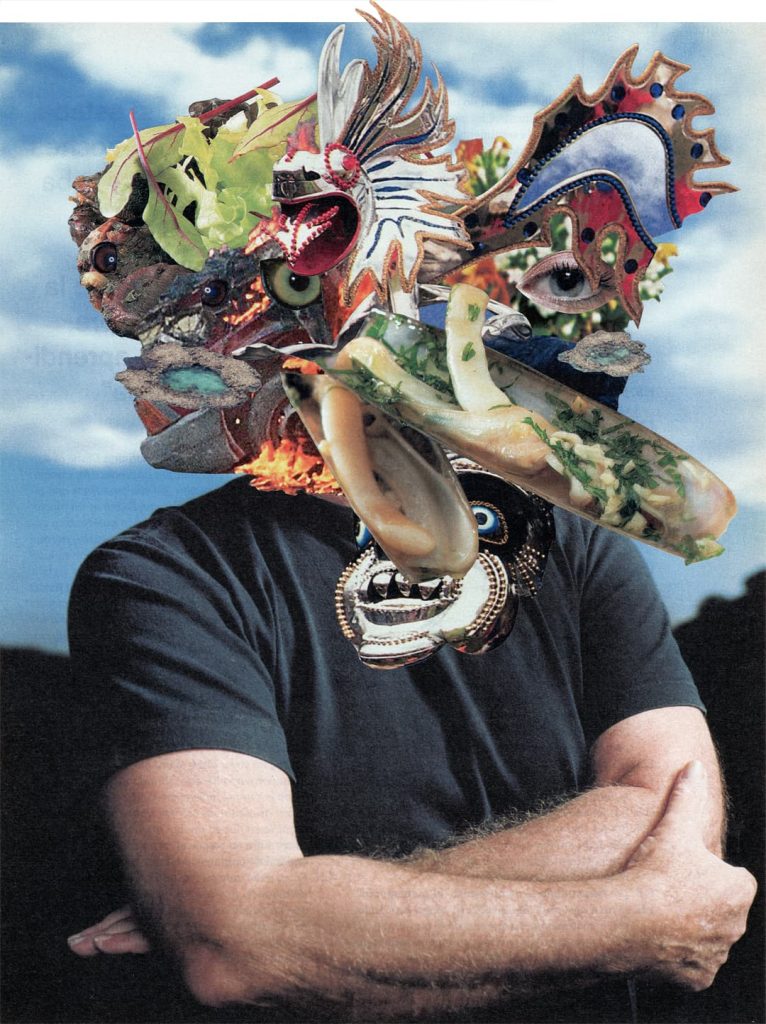

TWS – What do you think remains from your time painting on the street in your current practice working with paper?

C – For me, it was essential to draw before going out to paint. I would sketch and refine the letters and style until I got the desired shape and perfect connections. In graffiti, as in collage, I learned from the best, practiced hard, and set high standards for myself. I stuck closely to the sketch and tried not to improvise. I wanted the letters on the wall to match what I had drawn on paper. I spent a lot of time ensuring the outlines and fillings were clean, and I’ve carried that perfectionism into my collage work. Though I enjoy improvising when cutting and pasting, I work first on a Photoshop sketch to see if the idea is worth executing. Once I’m happy with the digital collage, I cut and paste by hand, following the digital version down to the millimeter. It drives me crazy to see that the analog version and the digital version are practically the same.

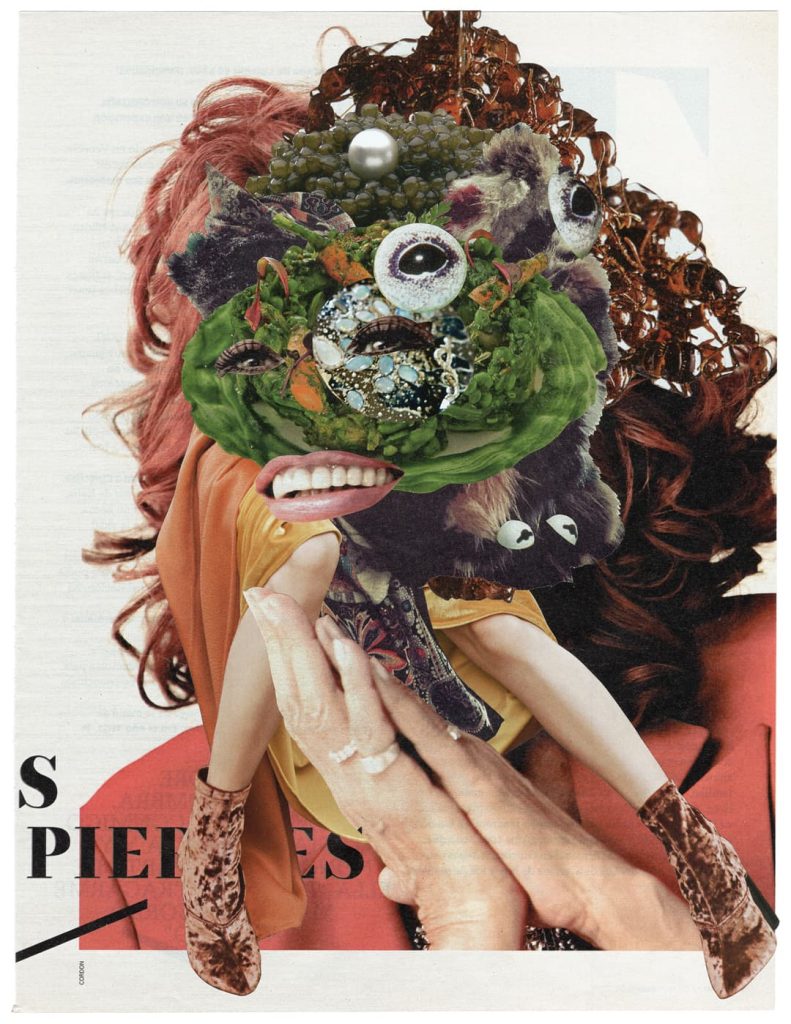

TWS – Imagine you’re in front of someone who has never seen your work (and you can’t show them a photo): How would you describe it? What would you explain?

C – I’d describe it as a bit ugly at first (please don’t be scared of that word). At first glance, it’s a complex mass that mixes many elements, but they all work together in harmony, especially the colors. I’d point out that each layer of paper, no matter how small, has its exact place and cannot move a millimeter. It’s all measured, literally. Lastly, I’d say it’s a deeply personal work, full of feeling—it’s like channeling my inner self. Basically it is as if my stomach had created it.

TWS – When I see and think of your work, I always associate it with the word “obsession.” Do you feel that obsession is an important part of your work?

C – Yes, I remember you used that word before, and I liked it. It’s true, though I hadn’t named it that way. Each piece must be trimmed perfectly and placed in the exact spot. I strive for precision, which can be exhausting. I love to cut out precisely and perfectly but also tear the paper on purpose while doing so, it is my personal seal. As I work, I observe for a long time the steps I’m taking at each stage of the composition. The process is very important to me, even if only a small percentage of people notice all the details.

TWS – What other obsessions do you have outside of collage?

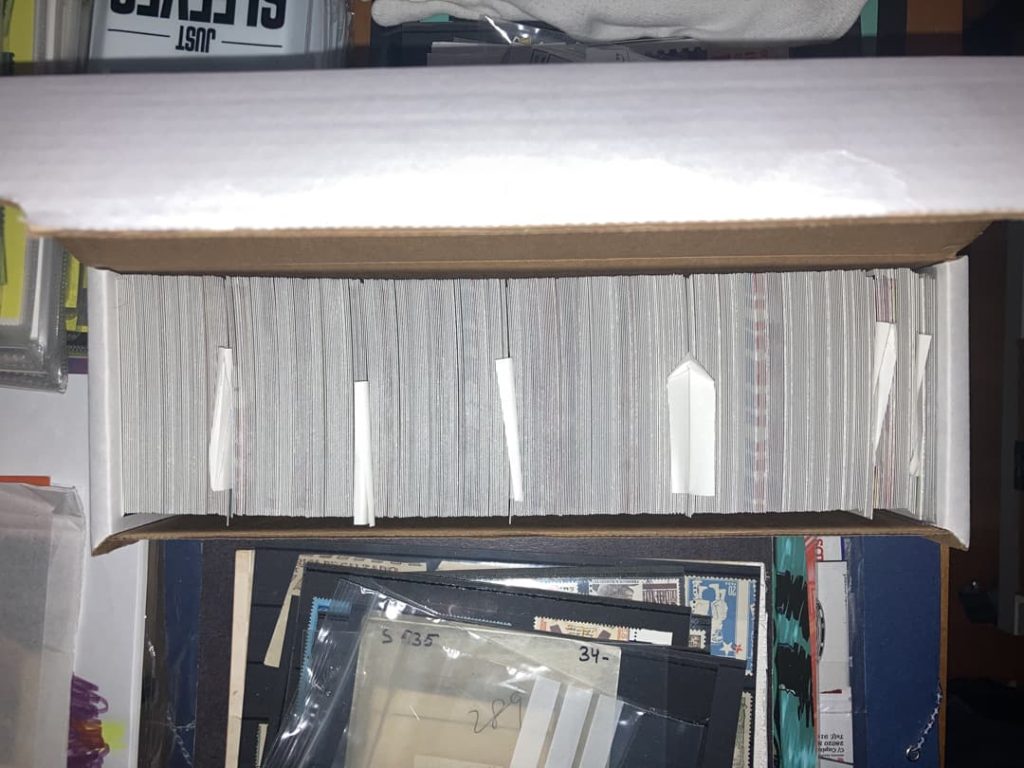

C – Oh my… I collect too many things LOL. I am concerned that this may be out of control. Mostly with books and zines but I also collect Art, Stamps, Trading Cards, Small pieces of paper, Spray Cans, Vinyl Toys, Tart Card, Labels, Fruit Stickers, Screenshots, Train Tickets, Cardboard, Metal Signs, things I pick up on the street and more. I’ve been collecting and storing for over 35 years. I don’t even know how I manage to store everything.

SEEK, FIND, GET! This on fire every day, EVERY DAY!

TWS – In the installation you’ve done for the exhibition “Los Raros. Las Raras.” you’ve displayed work created from postage stamps. Could you tell us more about this project? Is your work moving away from traditional collage?

C – Well, let’s say that I have several projects going on simultaneously. In the end, everything revolves around paper, and I started collecting stamps when I was 10 years old. I didn’t keep it up for long because I was young and didn’t have much money. Soon after, I got hooked on graffiti, which was always expensive. With my small budget, I couldn’t cover everything, so I had to put philately aside for graffiti. Fortunately, a pandemic came along (what a fucking moment!), and it changed everyone’s life. I remember looking at graphs of the pandemic every day, seeing how infections were increasing worldwide. I would take screenshots and save them. That affected me a lot, especially because I care for my mother, who relies on artificial respiration. To be honest, I thought we were all going to die. Now it sounds dramatic, but at the time it stopped my collage work for almost three years. Fortunately, I remembered my stamp collection and thought it could keep me entertained, and it did. I don’t want to say too much because this is more than four years of stamp therapy, but I invested time and money in my collection and found new relationships between stamps, collage, and art. I started looking at stamps not just as collectibles but as pieces of art, and their imperfections fascinated me. That blew my mind and opened new doors in my work. Parallel to my collection of books and objects, this helped me get back into collage and provided me with new creative paths.

TWS – You’ve been off social media for a long time. What led you to make that decision? What impact has it had on your work? What do you think about everything that has developed around social media and the dependence many of us have on it?

C – I had a really hard time a few years ago, and the pandemic finished it off. I think that already in 2018, I noticed that what I published wasn’t reaching anyone—it wasn’t visible. I’m not just talking about likes; the work itself wasn’t getting seen by many people, and I got the sense that there was no interest in it. This was the beginning of the algorithm, I guess. I remember many conversations with you about it, and also with David Fresno. We even discussed changing the way we worked to play by their rules, to reach more people. But I couldn’t do it—something inside me wouldn’t let me work like that, and the last thing I wanted was to let myself down. It also became personal, and it really drained me. It took a lot of time and energy at an already difficult time. It felt like Cless (or insert your own name) had to become a business and produce non-stop, and the kind of work I was doing wasn’t rewarded. I think Instagram did and is doing a lot of damage to many people. From a distance, stepping back for family reasons gave me some perspective, and it was healing. Unfortunately, if you’re not on Instagram, you’re considered dead. So you have to come back from time to time to show you’re still here, that you’re still alive, just like in graffiti—getting up, even if it’s only for a few.

TWS – What have we left out? What else should we know to understand Cless in 2024?

C – I’m sure we left something out, no doubt. And yes, I guess I’ve gone through a kind of Digivolution. Like my work, I’m complex and need more time and words to explain all the reasons behind it. But maybe we need an audiobook and a dose of vitamins to get through the challenge. The Cless of 2024 wants what the Cless of 2000 wanted: to keep working, exploring, and seeing where the next works and projects take him. He wants to enjoy them as his biggest fan, keep learning, discovering, and testing. It’s sometimes difficult, but to do that, you have to keep moving forward and betting on yourself. I’ll leave you with a quote from Jeff Koons that became a mantra for me: “I don’t believe that you can create art. But I believe what will lead you to art is to trust in yourself, follow your interests, and focus on your interests. That will take you to a very metaphysical state.” Coincidentally, my brother Nane used to tell me something very similar: Trust in yourself and do what you like! Maybe you don’t see me on IG but Hey! I’m still here and paraphrasing Osbourne Cox a.k.a John Malkovich: I’m bigger, I’m back. I’m better, I’m back. You fuckers I’m back! A THOUSAND thanks for believing and betting on me, Max. Thanks to all of you for making it this far. Lots of love!